- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 What Is Global Studies?

Professor Manfred B. Steger, Director, Globalism Research Centre, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

- Published: 11 December 2018

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter provides an overview of the emerging field of global studies by introducing readers to its growing institutional significance in global higher education. Drawing on influential arguments of major thinkers in global studies to their own framework, the chapter discuss the “four pillars of global studies”: globalization, transdisciplinarity, space and time, and critical thinking. Having presented the new field’s conceptual and thematic framework, this chapter closes by considering its capacity for self-criticism. After all, the critical thinking framing of global studies creates a special obligation for all scholars working in the field to listen to and take seriously internal and external criticisms with the intention of correcting existing shortcomings, illuminating blind spots, and avoiding theoretical pitfalls and dead ends.

Although scholars within the field of global studies (GS) debate over how to define the term, most agree that it has emerged in the twenty-first century as a multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary field of inquiry dedicated to the exploration of the many dimensions of globalization and other transnational phenomena. Perhaps the most important keyword of our time, “globalization” remains a contested and open-ended concept, especially with respect to its normative implications. Although the phenomenon has been extensively studied in sociology, economics, anthropology, geography, history, political science, and other fields, it falls outside the established disciplinary framework. After all, “globalization” is only of secondary concern in these traditional fields organized around different master concepts: “society” in sociology, “resources” and “scarcity” in economics, “culture” in anthropology, “space” in geography, “the past” in history, “power” and “governance” in political science, and so on. By contrast, GS has placed the keyword without a firm disciplinary home at the core of its intellectual enterprise. The rise of GS, therefore, not only represents a clear sign of the proper recognition of new kinds of social interdependence and enhanced forms of mobility but also demonstrates that the nineteenth-century realities that gave birth to the conventional disciplinary architecture are no longer ours ( Jameson 1998 : xi). At the same time, however, GS is not hermetic, for it welcomes various approaches and methods that contribute to a transnational analysis of the world as a single interactive system.

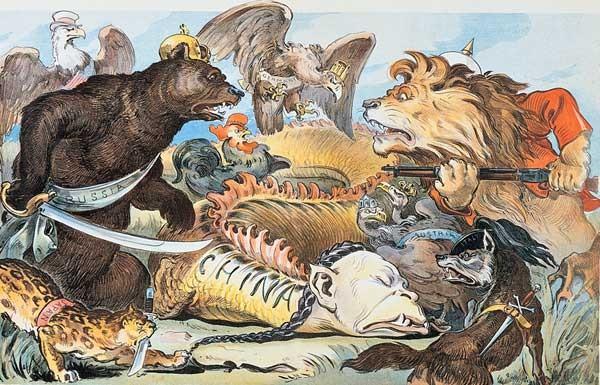

The field of GS is sometimes compared to the disciplines of international relations (IR) and international studies (IS). Still, their differences clearly outweigh their similarities. Mainstream IR considers the state as the principal mover of world politics and thus the central unit of analysis. This means that the actions of states—especially with regard to security issues—are foregrounded at the expense of other crucial areas, such as economics and culture. By contrast, GS researchers consider the state as but one actor in today’s fluid web of material and ideational interdependencies that includes proliferating non-state entities, nongovernmental organizations, transnational social movements, and other social and political forces “beyond the state.” 1 This multicentric and multidimensional understanding of our globalizing world makes GS a porous field with strong “applied” interests in public policy. GS scholars frequently seize upon issues that are often excluded from IR—for example, issues connected to gender, poverty, global media, public health, migration, and ecology. This problem-centered focus of GS encourages the forging of strong links among the worlds of academia, political organizations, nongovernmental organizations, and social movements.

Most important, GS both embraces and exudes a certain mentalité , which I have called the “global imaginary” ( Steger 2008 ; Steger and James 2013 ). It refers to a sense of the social whole that frames our age as one shaped by the intensifying forces of globalization. Giving its objective and subjective aspects equal consideration, GS suggests that enhanced interconnectivity does not merely happen in the world “out there” but also operates through our consciousness “in here.” To recognize the significance of global consciousness, however, does not support premature proclamations of the “death of the nation-state.” Conventional national and local frameworks have retained significant power as well as reconfigured those central functions. Although the nation-state is not dying, globalization has forced it to accommodate an incipient and slowly evolving architecture of “global governance.” Hence, it is not surprising that GS researchers show great interest in transnational educational initiatives centered on the promotion of “global citizenship” and other “embedded” cosmopolitan visions that link the local to the global and vice versa.

In the roughly two decades of its existence, GS has attracted scores of unorthodox faculty and unconventional students who share its sincere commitment to studying transnational processes, interactions, and flows from multiple and transdisciplinary perspectives. Still, there are large sections of the academic community that have either not heard of GS at all or are still unclear about its scope and methods. So what, exactly, is GS and what does it entail? Responding to these persistent demands for clarification, this chapter seeks to provide a general overview of the main contours and central features of GS. 2 Although scores of globalization scholars still quarrel over what themes and approaches their field should or should not encompass, it would be a mistake to close one’s eyes to existing agreements and common approaches that have become substantial enough to identify four central “pillars” or “framings” of GS: globalization, transdisciplinarity, space and time, and critical thinking. But before presenting the new field’s conceptual and thematic framework in more detail, let us start by considering some important institutional developments that have aided its rapid growth.

The Institutional Growth of Global Studies

Creating a special academic context for the study of globalization, GS has become gradually institutionalized in the academy. Yet, GS does not view itself as just another cog in the disciplinary machine of contemporary higher education. Despite today’s trendy talk about “globalizing knowledge” and “systematic internationalization”—which is often more about the neoliberal reinvention of the academy as “big business” than about creating new spaces of epistemological diversity—the traditional Western academic framework of knowledge specialization has survived largely intact into the twenty-first century. Often forced to make compromises and find less than desirable accommodations with the dominant academic order, GS challenges a fractured, Eurocentric mindset that encourages the division of knowledge into sharply demarcated areas populated by disciplinary “insiders.” Although it seeks to blaze new trails of social inquiry, GS is not afraid of presenting itself as a fluid and porous intellectual terrain rather than a novel, well-defined item on the dominant disciplinary menu. To use Fredric Jameson’s (1998: xvi) felicitous term, the new field inhabits an academic “space of tension” framed by multiple disagreements and agreements in which the very problematic of globalization itself is being continuously produced and contested.

The educational imperative to grasp the complex spatial and social dynamics of globalization animates the transdisciplinary efforts of GS to reorder human knowledge and create innovate learning environments. Relying on conceptual and analytic perspectives that are not anchored in a single discipline, the new field expands innovative interdisciplinary approaches pioneered in the 1970s and 1980s, such as world-systems analysis, postcolonial studies, cultural studies, environmental and sustainability studies, and women’s studies. The power of the rising global imaginary and its affiliated new ideologies of “market globalism,” justice globalism, and religious globalisms goes a long way in explaining why GS programs, departments, research institutes, and professional organizations have sprung up in major universities throughout the world, including in the Global South ( Steger 2013 ). Recognizing this trend, many existing IS programs have been renamed “global studies.” Demand for courses and undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in GS has dramatically risen. Increasingly, we see the inclusion of the terms “global” or “globalization” in course titles, textbooks, academic job postings, and extracurricular activities. Universities and colleges in the United States have supported the creation of new GS initiatives that are often funded by major government institutions and philanthropists. For example, Northwestern University recently announced a donation of $100 million—the largest single gift in its history—from the sister of the prominent investor Warren Buffett for the establishment of the Roberta Buffett Institute for Global Studies.

Drawing on thematic and methodological resources from the social sciences and humanities, GS now encompasses approximately 300 undergraduate and graduate programs in the United States alone. 3 Some pioneering universities, such as the University of California, Santa Barbara or the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, house programs that serve nearly 1,000 GS undergraduate majors. The Division of Global Affairs at Rutgers University–Newark and RMIT University’s (Melbourne, Australia) School of Global, Urban, and Social Studies accommodate hundreds of master’s and doctoral students. In 2015, the University of California, Santa Barbara launched the first doctoral program in GS at a tier 1 research university in the United States. In addition to the creation of these successful degree-granting programs, there has been a phenomenal growth of scholarly literature on globalization. New journals, book series, textbooks, academic conferences, and professional associations such as the international Global Studies Consortium or the Global Studies Association have embraced the novel umbrella designation of “global studies.”

Clearly, the fledgling field and its associated global imaginary have come a long way in a relatively short period of time. However, its success also depended to a significant extent on the redirection of funding by US government and philanthropic organizations from established IS and area studies programs to the newcomer “global studies.” Indeed, this reorientation toward GS occurred in the ideological context of the rise of “neoliberalism,” an economistic doctrine at the core of a comprehensive worldview I have called “market globalism” ( Steger and Roy 2010 ). As Isaac Kamola’s (2010) pioneering work on the subject has demonstrated, starting in the mid-1990s, a number of important funders announced plans to replace “area” structures with a “global” framework. For example, the Social Science Research Council recommended defunding “discrete and separated area committees” that were reluctant to support scholars interested in “global” developments and policy-relevant “global issues.” When conventional area studies experts realized that traditional sources of funding were quickly drying up, many joined the newly emerging GS cohort of scholars centered on the study of “globalization.” Major universities, too, reduced the level of support for area studies teaching and research programs while developing new investment schemes and strategic plans that provided for the creation of new “global studies” or “global affairs” programs and centers. Major professional organizations such as the National Association of State Universities and Land Grant Colleges and the American Association of Colleges and Universities eagerly joined these instrumental efforts to synchronize the initiatives of “globalizing the curriculum” and “recalibrating college learning” to the shifting economic landscape of the “new global century” ( Kamola 2010 ).

Convinced that GS programs will earn a more prominent place within the quickly changing twenty-first-century landscape of higher education characterized by shrinking budgets and new modes of instruction, a growing number of academics—loosely referred to in this chapter as “global studies scholars”—have begun to synthesize various common theoretical perspectives and problem-oriented approaches. Their efforts have contributed to the necessary mapping exercise without falling prey to the fetish of disciplinary boundary making. Building on these efforts, I contend in this chapter that it is now possible to present GS as a reasonably holistic transdisciplinary project dedicated to exploring processes of globalization with the aim of engaging the complex global problems the world is facing in the twenty-first century ( McCarty 2014 ). To this purpose, the next four sections of this chapter offer a general overview of the four major conceptual framings that give coherence to the field.

The First Pillar of Global Studies: Globalization

Globalization is the principal subject of GS and thus constitutes the first pillar of the emerging field. At the same time, the global also serves as the conceptual framework through which GS scholars investigate the contemporary and historical dynamics of thickening interdependence. The birth and rising fortunes of GS are inextricably linked to the emergence of globalization as a prominent theme in late twentieth-century public discourse. But the buzzword was not invented ex nihilo during the neoliberal Roaring Nineties as shorthand for the liberalization and worldwide integration of markets. In fact, it had been used as early as the 1930s in academic fields as varied as education and psychology, society and culture, politics and IR, and economics and business ( Steger and James 2015 ). At the same time, the powerful ideological and political dynamics of the 1990s served as crucial catalysts for the cross-fertilization of public and academic discourses on the subject. These raging globalization debates of the past decades attest to enormous interest in the academic study of globalization as a multidimensional phenomenon.

Attempts to develop objective, quantifiable assessments of the causes, contents, and consequences of globalization have become a key issue for contemporary social science research and social policy. Researchers have sought to develop empirical measures of globalization based on various indicators. These efforts led to the rapid proliferation of major globalization indices such as the KOF Index of Globalization. 4 Today, readers interested in globalization can select among thousands and thousands of pertinent books, articles, and encyclopedia entries. In our digital age, these writings can be tracked down with unprecedented speed and precision through new technologies such as the search engine Ngram, Google’s mammoth database collated from more than 5 million digitized books available free to the public for online searches. In 2015, the exceptionally rich Factiva database listed 355,838 publications referencing the term “globalization.” The Expanded Academic ASAP database produced 7,737 results with “globalization” in the title, including 5,976 journal articles, 1,404 magazine articles, and 355 news items. The ISI Web of Knowledge listed a total of 8,970 references with “globalization,” the EBSCO Host Database yielded 17,188 results, and the Proquest Newspaper Database showed 25,856 articles.

Despite continuing disagreements regarding how to define globalization, GS scholars have put forward various definitions and collected them in comprehensive classification tables ( Al-Rodhan and Stoudmann 2006 ). One major obstacle in the way of producing useful definitions of globalization is that the term has been variously used in both academic literature and the popular press to describe a process, a condition, a system, a force, and an age. Given that these concepts have very different meanings, their indiscriminate usage is often obscure and invites confusion. For example, a sloppy conflation of process and condition encourages circular definitions that explain little. The familiar truism that globalization (the process) leads to more globalization (the condition) does not allow us to draw meaningful analytical distinctions between causes and effects. Hence, we ought to adopt the term globality to signify a social condition characterized by extremely tight global economic, political, cultural, and environmental interconnections across national borders and civilizational boundaries. The term globalization , by contrast, applies not to a condition but a multidimensional set of social processes pushing toward globality.

GS scholars exploring the dynamics of globalization are particularly keen on pursuing research questions related to themes of social change, which connect the human and natural sciences. How does globalization proceed? What is driving it? Is it one cause or a combination of factors? Is globalization a continuation of modernity or is it a radical break? Does it create new forms of inequality and hierarchy or is it lifting millions of people out of poverty? Is it producing cultural homogeneity or diversity? What is the role of new technologies in accelerating and intensifying global processes? Note that the conceptualization of globalization as a dynamic process rather than as a static condition also highlights the fact that it is an uneven process: People living in various parts of the world are affected very differently by the transformation of social structures and cultural zones.

The principal voices in the academic globalization debates can be divided into four distinct intellectual camps: globalizers, rejectionists, skeptics, and modifiers. Most GS scholars fall into the category of globalizers , who argue that globalization is a profoundly transformative set of social processes that is moving human societies toward unprecedented levels of interconnectivity ( Held and McGrew 2002 ; Mittelman 2000 ; Scholte 2005 ). While committed to a big picture approach, globalizers nonetheless tend to focus their research efforts on one of the principal dimensions of globalization: economics, politics, culture, or ecology. By contrast, rejectionists contend that most of the accounts offered by globalizers are incorrect, imprecise, or exaggerated. Arguing that such generalizations often amount to little more than “globaloney,” they dismiss the utility of globalization for scientific academic discourse ( Veseth 2010 ). Their contention that just about everything that can be linked to some transnational process is often cited as evidence for globalization and its growing influence. The third camp in the contemporary globalization debates consists of skeptics who acknowledge some forms and manifestations of globalization while also emphasizing its limited nature ( Hirst et al. 2009 ; Rugman 2001 ). Usually focusing on the economic aspects of the phenomenon, skeptics claim that the world economy is not truly global but, rather, a regional dynamic centered on Europe, East Asia, Australia, and North America. The fourth camp in these academic debates consists of modifiers who acknowledge the power of globalization but dispute its novelty and thus the innovate character of social theories focused on the phenomenon. They seek to modify and assimilate globalization theories to traditional approaches in IS, world-systems theory, or other related fields, claiming that a new conceptual paradigm is unwarranted ( Wallerstein 2004 ).

In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that neither modifiers nor rejectionists have offered convincing arguments for their respective views. Although objections to the overuse of the term have forced the participants in the globalization debates to hone their analytic skills, the wholesale rejection of globalization as a “vacuous concept” has often served as a convenient excuse to avoid dealing with the actual phenomenon itself. Rather than constructing overly ambitious “grand narratives” of globalization, many GS researchers in the globalizers and skeptics camps have instead wisely opted for more modest approaches that employ mixed methodologies designed to provide explanations of particular manifestations of the process.

The Second Pillar of Global Studies: Transdisciplinarity

The profound changes affecting social life in the global age require examinations of the growing forms of complexity and reflexivity ( Giddens 1990 ). This means that the global dynamics of interconnectivity can no longer be approached from a single academic discipline or area of knowledge. Emphasizing the analysis of global complexity and reflexivity commits GS scholars to the development of more comprehensive explanations of globalization, which highlight the complex intersection between a multiplicity of driving forces, embracing economic, technological, cultural, and political change ( Held et al. 1999 ). Hence, the conceptual frameworks of influential GS researchers explore these growing forms of interdependence through “domains,” “dimensions,” “networks,” “flows,” “fluids,” and “hybrids”—the key terms behind their transdisciplinary attempts to globalize the social science research imagination ( Castells 2010 ; Kenway and Fahey 2008 ; Urry 2003 ). Recognizing the importance of increasing complexity for their systematic inquiries, they consciously embrace transdisciplinarity in their efforts to understand the shifting dynamics of interconnectedness. Thus, their exploration of complex forms of global interdependence not only combats knowledge fragmentation and scientific reductionism but also facilitates an understanding of the “big picture,” which is indispensable for stimulating the political commitment needed to tackle the pressing global problems of our time. Multidimensional processes of globalization and their associated global challenges, such as climate change, pandemics, terrorism, digital technologies, marketization, migration, urbanization, and human rights, represent examples of transnational issues that both cut across and reach beyond conventional disciplinary boundaries.

Although university administrators in the United States and elsewhere have warmed up to interdisciplinarity, most instructional activities in today’s institutions of higher education still occur within an overarching framework of the disciplinary divisions. The same holds true for academic research in the social sciences and humanities, where scholars continue to produce specialized problems to which solutions can be found primarily within their own disciplinary orientations. 5 Critical of this tendency to compartmentalize the complexity of social existence into discrete spheres of activity, GS has evolved as a self-consciously transdisciplinary field committed to the engagement and integration of multiple knowledge systems and research methodologies. Typically hailing from traditional disciplinary backgrounds, faculty members are often attracted to GS because they are deeply critical of the entrenched conventions of disciplinary specialization inherent in the Eurocentric academic framework. Appreciative of a more flexible intellectual environment that allows for the bundling of otherwise disparate conceptual fields and geographical areas into a single object of study, GS scholars seek to overcome such forms of disciplinary “silo thinking.”

The concept of “transdisciplinarity” is configured around the Latin prefix “trans” (“across” or “beyond”). It signifies the systemic and holistic integration of diverse forms of knowledge by cutting across and through existing disciplinary boundaries and paradigms in ways that reach beyond each individual discipline. If interdisciplinarity can be characterized by the mixing of disciplinary perspectives involving little or moderate integration, then transdisciplinarity should be thought of as a deep fusion of disciplinary knowledge that produces new understandings capable of transforming or restructuring existing disciplinary paradigms ( Alvargonzalez 2011 ; Repko 2012 ). But the transdisciplinary imperative to challenge, go beyond, transgress, and unify separate orientations does not ignore the importance of attracting scholars with specific disciplinary backgrounds. Moreover, transdisciplinarians put complex real-world problems at the heart of their intellectual efforts. The formulation of possible resolutions of these problems requires the deep integration of a broad range of perspectives from multiple disciplinary backgrounds ( Pohl 2010 : 69; Pohl and Hadorn 2008 : 112).

Yet, full transdisciplinarity—understood as activities that transcend, recombine, and integrate separate disciplinary paradigms—remains an elusive goal for most academics. This includes GS scholars associated with currently existing academic programs in the field. Some have achieved a high degree of transdisciplinary integration, whereas others rely more on multi- and interdisciplinary activities that benefit students and faculty alike. For GS, the task is to expand its foothold in the dominant academic landscape while at the same time continuing its work against the prevailing disciplinary order. To satisfy these seemingly contradictory imperatives, GS has retained its ambition to project globalization across the conventional disciplinary matrix while at the same time accepting with equal determination the pragmatic task of finding some accommodation within the very disciplinary structure it seeks to transform. Such necessary attempts to reconcile these diverging impulses force scholars to play at least one, and preferably more, of three distinct roles—depending on the concrete institutional opportunities and constraints they encounter in their academic home environment.

First, GS scholars often assume the role of intrepid mavericks willing to establish GS as a separate discipline—as a first but necessary step toward the more holistic goal of comprehensive integration. To be sure, mavericks possess a certain spirit of adventure that makes it easier for them to leave their original disciplinary setting behind to cover new ground. But being a maverick also carries the considerable risk of failure. Second, a number of GS scholars have embraced the role of radical insurgents seeking to globalize established disciplines from within. This means working toward the goal of carving out a GS dimension or status for specific disciplines such as political science or sociology. Finally, some GS faculty have slipped into the role of tireless nomads traveling perpetually across and beyond disciplines in order to reconfigure existing and new knowledge around concrete globalization research questions and projects. The nomadic role, in particular, demands that academics familiarize themselves with vast literatures on pertinent subjects that are usually studied in isolation from each other. Indeed, one of the most formidable intellectual challenges lies in the integration and synthesis of multiple strands of knowledge in a way that does justice to the complexity and fluidity of our globalizing world.

The Third Pillar of Global Studies: Space and Time

The development of GS has been crucially framed by new conceptions of space and time. After all, globalization manifests in volatile dynamics of spatial integration and differentiation. These give rise to new temporal frameworks dominated by notions of instantaneity and simultaneity, which assume ever-greater significance in academic investigations into globalization. Thus deeply resonating with spatio-temporal meanings, the keyword unites two semantic parts: “global” and “ization.” The primary emphasis is on “global,” which reflects people’s growing awareness of the increasing significance of global-scale phenomena such as global economic institutions, transnational corporations, global civil society, the World Wide Web, global climate change, and so on. Indeed, the principal reason the term was coined in the first place had to do with people’s recognition of intensifying spatio-temporal dynamics. Globalization processes create incessantly new geographies and complex spatial arrangements. This is especially true for the latest spatial frontier in human history: cyberspace. The dynamics of digital connectivity have shown themselves to be quite capable of pushing human interaction deep into the “virtual reality” of a world in which geography is no longer a factor.

Several GS pioneers developed approaches to globalization that put matters of time and space at the very core of their research projects. Consider, for example, Roland Robertson’s (1992: 6–7) snappy definition of globalization as “the compression of the world into a single place.” It underpinned his efforts to develop a spatially sophisticated concept of “glocalization” capable of counteracting the relative inattention paid to spatiality in the social sciences. Commenting on the remarkable fluidity of spatial scales in a globalizing world, Robertson focused on those complex and uneven processes “in which the constraints of geography on social and cultural arrangements recede and in which people become increasingly aware that they are receding” ( Robertson 2005 ). Similarly, Arjun Appadurai (1996: 188) developed subtle insights into what he called the “global production of locality”—a new spatial dynamic that was occurring more frequently in “a world that has become deterritorialized, diasporic, and transnational.” Or consider David Harvey’s (1989: 137, 265, 270–273) influential inquiry into the spatial origins of contemporary cultural change centered on the uneven geographic development of capitalism. His innovative account generated new concepts such as “time–space compression” or “the implosion of space and time,” which affirmed the centrality of spatio-temporal changes at the heart of neoliberal globalization and its associated postmodern cultural sensibilities.

GS scholars have explored a number of crucial spatio-temporal themes, such as the ongoing debate concerning whether globalization represents the consequence of modernity or a postmodern break, the changing role of the nation-state, the changing relationship between territory and sovereignty, the growing significance of global cities, the increasing fluidity of spatial scales, new periodization efforts around time and space, and the emergence of global history as a transdisciplinary endeavor. Let us consider, for example, the crucial dynamics of “deterritorialization.” “Territoriality” refers to the use of territory for political, social, and economic ends. In modernity, the term has been associated with a largely successful strategy for establishing the exclusive jurisdiction implied by state “sovereignty” ( Agnew 2009 : 6). State control of bounded “national” terrain promised citizens living on the “inside” the benefits of relative security and unity in exchange for their exclusive loyalty and allegiance to the nation-state. By the second half of the twentieth century, social existence in such relatively fixed spatial containers had gone on for such a long time that it struck most people as the universal mode of communal life in the world. However, the latest wave of globalization gathering momentum in the 1980s and 1990s exposed the artificiality of territoriality as a social construct and its historical role as a specific human technique for managing space and time in the interests of modern state power.

The impact of globalization on conventional forms of territoriality and the related changing nature of the “international system” have raised major questions concerning the significance of the nation-state and the relevance of conventional notions of “territory” and “sovereignty” in analyzing the new spatial practices associated with globalization. This new spatial agenda also involves an important subset of issues pertaining to the proliferation and growing impact of non-state actors; the emergence of a “global civil society” no longer confined within the borders of the territorial state; the prospects for global governance understood as the norms and institutions that define and mediate relations between citizens, societies, markets, and states on a global scale; and the pluralization and hybridization of individual and collective identities. Various commentators have pointed to a growing gap between global space, where new problems arise, and national space, which proves increasingly inadequate for managing these transnational issues ( Castells 2008 ; Thakur and Weiss 2011 ). These mounting spatial incompatibilities combine with the increasing power of neoliberalism and the absence of effective institutions of global governance to produce interrelated crises of state legitimacy and economic equity that undermine democratic politics.

Although there is virtual agreement among GS scholars that today’s respatialization dynamics are profound and accelerating, there remain significant differences between a small band of thinkers comfortable with advancing an extreme thesis of “absolute” deterritorialization and a much larger group holding more moderate, “relativist” views. Absolutist views rose to prominence during the 1990s when spectacular neoliberal market reforms diminished the role of the state in the economy. Politics anchored in conventional forms of territoriality was seen as losing out to the transnational practices of global capitalism in which the state’s survival in diminished form depended on its satisfactory performance of its new role as a handmaiden to global free-market forces ( Ohmae 1996 ).

While acknowledging the growing significance of deterritorialization dynamics in a globalizing world, relativists argued for the continued relevance of sub-global territorial units, albeit in reconfigured forms. The increasing inability of nation-states to manage the globalization processes forced them to change into what Manuel Castells (2008: 88) calls the “network state,” characterized by shared sovereignty and responsibility, flexibility of procedures of governance, and greater diversity in the relationships between governments and citizens in terms of time and space. Similarly, Saskia Sassen (2007) and Neil Brenner (1999) suggest that globalization involves not only the growth of supraterritoriality but also crucial processes and practices of “down-scaling” that occur deep inside the local, national, and regional. Perhaps the most critical of these spatial restructuring processes facilitated by states involves the localization of the control and command centers of global capitalism in “global cities” that assume great significance as pivotal places of spatial dispersal and global integration located at the intersection of multiple global circuits and flows involving migrants, ideas, commodities, and money ( Sassen 2001 ).

As our discussion of the third pillar of GS has shown, the field owes much to the efforts of innovative human geographers and urban studies experts to develop new theoretical approaches that help us understand the changing spatial dynamics of our time. But GS is equally indebted to the intellectual initiatives of sociologists and historians willing to rethink the conceptual frameworks governing the temporal record of human activity. The emergent field of global history, for example, is based on the central premise that processes of globalization require more systematic historical treatments and, therefore, that the study of globalization deserves a more prominent place on the agenda of historical research ( Clarence-Smith, Pomeranz, and Vries 2006 ; Hopkins 2002 ; Mazlish 2006 ; Mazlish and Iriye 2005 ). Parting with narratives centered on the development of nations or Eurocentric “world histories,” global historians investigate the emergence of our globalized world as the result of exchanges, flows, and interactions involving many different cultures and societies—past and present. Recognizing the historical role of powerful drivers of globalization, many GS scholars have integrated historical schemes in their study of intensifying human interactions across geographical, conceptual, and disciplinary boundaries.

The Fourth Pillar of Global Studies: Critical Thinking

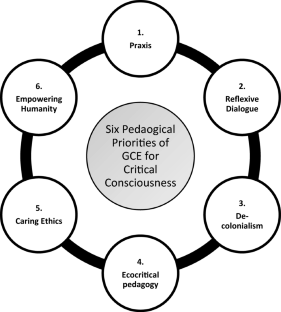

Few GS scholars would object to the proposition that their field is significantly framed by “critical thinking.” After all, GS constitutes an academic space of tension that generates critical investigations into our age as one shaped by the intensifying forces of globalization. Going beyond the purely cognitive understanding of “critical thinking” as “balanced reasoning” propagated by leading Anglo-American educators during the second half of the twentieth century, this fourth pillar reflects the field’s receptivity to the activity of social criticism that problematizes unequal power relations and engages in ongoing social struggles to bring about a more just global society.

Advancing various critical perspectives, GS scholars from throughout the world draw on different currents and methods of “critical theory”—an umbrella term for modes of thought committed to the reduction of exploitation, commodification, violence, and alienation. Such a “critical global studies” (CGS) calls for methodological skepticism regarding positivistic dogmas and “objective facts”; the recognition that some facts are socially constructed and serve particular power interests; the public contestation of uncritical mainstream stories spun by corporate media; the decolonization of the Western imagination; and an understanding of the global as a multipolar dynamic reflecting the concerns of the marginalized Global South even more than those of the privileged North. Taking sides with the interest of social justice, CGS thinkers exercise what William Robinson (2005: 14) calls a “preferential option for the subordinate majority of global society.”

There is much empirical evidence to suggest that dominant neoliberal modes of globalization have produced growing disparities in wealth and well-being within and among societies. They have also led to an acceleration of ecological degradation, new forms of militarism and digitized surveillance, previously unthinkable levels of inequality, and a chilling advance of consumerism and cultural commodification. The negative consequences of such a corporate-led “globalization-from-above” became subject to democratic contestation in the 1990s and impacted the evolution of critical theory in at least two major ways. First, they created fertile conditions for the emergence of powerful social movements advocating a people-led “globalization-from-below.” These transnational activist networks, in turn, served as catalysts for the proliferation of new critical theories developing within the novel framework of globalization.

Many CGS thinkers were inspired by local forms of social resistance to neoliberalism, such as the 1994 Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, Mexico; the 1995 strikes in France and other areas of Europe; and the powerful series of protests in major cities throughout the world following in the wake of the iconic 1999 anti-World Trade Organization demonstration in Seattle. Critical intellectuals interacted with the participants of these alter-globalization movements at these large-scale protest events or at the massive meetings of the newly founded World Social Forum in the 2000s. They developed and advanced their critiques of market globalism in tandem with constructive visions for alternative global futures. Because the struggles over the meanings and manifestations of globalization occurred in interlinked local settings throughout the world, they signified a significant alteration in the geography of critical thinking. As French sociologist Razmig Keucheyan (2013: 3) has emphasized, the academic center of gravity of these new forms of critical thinking was shifting from the traditional centers of learning located in Old Europe to the top universities of the New World. The United States, in particular, served as a powerful economic magnet for job-seeking academics from throughout the world while also posing as the obvious hegemonic target of their criticisms.

Indeed, during the past quarter century, America has managed to attract a large number of talented postcolonial critical theorists to its highly reputed and well-paying universities and colleges. A significant number of these politically progressive recruits, in turn, promptly put their newly acquired positions of academic privilege into the service of their socially engaged ideologies, which resulted in a vastly more effective production and worldwide dissemination of their critical publications. Moreover, the global struggle against neoliberalism that heated up in the 1990s and 2000s also contributed significantly to the heightened international exposure of cutting-edge critical theorists located in the vast terrains of Asia, Latin America, and Africa. In particular, the permanent digital communication revolution centered on the World Wide Web and the new social media made it easier for these voices of the Global South to be heard in the dominant North. In fact, the “globalization of critical thinking” culminated in the formation of a “world republic of critical theories” ( Keucheyan 2013 : 21, 73). Although this global community of critical thinkers is far from homogeneous in its perspectives and continues to be subjected to considerable geographic and social inequalities, it has had a profound influence on the evolution of GS.

Still, we need to be careful not to exaggerate the extent to which such CGS perspectives pervade the field. Our discussion of the developing links between the global justice movement and CGS scholars should not seduce us into assuming that all academics affiliated with GS programs support radical or even moderate socially engaged perspectives on what constitutes their field and what it should accomplish. After all, global thinking is not inherently “critical” in the socially engaged use of the term. An informal perusal of influential globalization literature produced during the past fifteen years suggests that nearly all authors express some appreciation for critical thinking understood as a cognitive ability to “see multiple sides of an issue” (in this case, the issue is “globalization”). But only approximately two-thirds of well-published globalization scholars take their understanding of “critical” beyond the social-scientific ideal of “balanced objectivity” and “value-free research” and thus challenge in writing the dominant social arrangements of our time and/or promote emancipatory social change ( Steger 2009 ). This locates the remaining one-third of globalization authors within a conceptual framework that transnational sociologist William Robinson (2005: 12) has provocatively characterized as “noncritical globalization studies.” Obviously, GS scholars relegated to this category would object to Robinson’s classification on the basis of their differing understanding of what “critical thinking” entails.

CGS scholars seek to produce globalization theory that is useful to emancipatory global social movements, and this is what animates their “global activist thinking.” Most of them could be characterized as “rooted cosmopolitans” who remain embedded in local environments while at the same time cultivating a global consciousness as a result of their vastly enhanced contacts to like-minded academics and social organizations across national borders. Stimulated by the vitality of emergent global civil society, CGS scholar–activists have thought of new ways of making their intellectual activities in the ivory tower relevant to the happenings in the global public sphere. These novel permutations of global activist thinking manifested themselves in the educational project of cultivating what is increasingly referred to as “global citizenship.” The teaching of these new civic values in GS has also been linked to the production of emancipatory knowledge that can be used directly in the ongoing struggle of the global justice movement against the dominant forces of globalization-from-above.

Concluding Remarks: Critiques of Global Studies

Having presented the new field’s conceptual and thematic framework, we might want to close this chapter by considering GS’s capacity for self-criticism. The critical thinking framing of GS creates a special obligation for all scholars working in the field to listen to and take seriously internal and external criticisms with the intention of correcting existing shortcomings, illuminating blind spots, and avoiding theoretical pitfalls and dead ends. As is the case for any newcomer bold enough to enter today’s crowded and competitive arena of academia, GS, too, has been subjected to a wide range of criticisms ranging from constructive interventions to ferocious attacks.

One influential criticism concerns the limited scope and status of “actual global studies as it is researched and taught at universities around the world” ( Pieterse 2013 : 504). For such critics, the crux of the problem lies with the field’s intellectual immaturity and lack of focus. They allege that currently existing GS programs and conferences are still relatively rare and haphazard; they resemble “scaffolding without a roof.” Finally, they bemoan the supposed dearth of intellectual innovators willing and able to provide necessary “programmatic perspectives on global studies” framed by those that are “multicentered and multilevel thinking,” and, therefore, capable of “adding value” to the field ( Pieterse 2013 : 505).

Such criticism resonates with the often shocking discrepancy between the rich conceptual promise of the field and the poor design and execution of “actual global studies as it is researched and taught at universities around the world.” There is some truth to complaints that a good number of GS programs lack focus and specificity, which makes the field appear to be a rather nebulous study of “everything global.” Like most of the other interdisciplinary efforts originating in the 1990s, GS programs sometimes invite the impression of a rather confusing combination of wildly different approaches reifying the global level of analysis. Another troubling development in recent years has been the use of “global studies” as a convenient catchphrase by academic entrepreneurs eager to cash in on its popularity with students. Thus, a desirable label has become attached to a growing number of conventional area studies curricula, IS offerings, and diplomacy and foreign affairs programs—primarily for the purpose of boosting their market appeal without having to make substantive changes to the traditional teaching and research agenda attached to such programs. Although some of these programs have in fact become more global over time, in other cases these instrumental appropriations of the GS label have not only caused much damage to the existing GS “brand” but also cast an ominous shadow on the future of the field.

Despite its obvious insights, however, Pieterse’s (2013) account of “actually existing global studies” strikes this writer as unbalanced and somewhat exaggerated. Much of the available empirical data show that there are promising pedagogical and research efforts underway in the field. These initiatives suggest that the instructive pessimism of the critics must be matched by cautious optimism. To be sure, an empirically based examination of the field shows GS as a project that is still very much in the making. Yet, the field’s tender age and relative inexperience should not deter globalization scholars from acknowledging the field’s considerable intellectual achievements and growing institutional infrastructure. GS “as it actually exists” has come a long way from its rather modest and eclectic origins in the 1990s. The regular meetings of the Global Studies Associations (United Kingdom and North America) and the annual convention of the Global Studies Consortium provide ample networking opportunities for globalization scholars from throughout the world. Moreover, GS scholars are developing serious initiatives to recenter the social sciences toward global systemic dynamics and incorporate multilevel analyses. They are rethinking existing analytical frameworks that expand critical reflexivity and methodologies unafraid of mixing various research strategies.

Another important criticism of GS comes from postcolonial thinkers located both within and without the field of GS. As Robert Young (2003) explains, postcolonial theory is a related set of perspectives and principles that involves a conceptual reorientation toward the perspectives of knowledges developed outside the West—in Asia, Africa, Oceania, and Latin America. By seeking to insert alternative knowledges into the dominant power structures of the West as well as the non-West, postcolonial theorists attempt to “change the way people think, the way they behave, to produce a more just and equitable relation between the different people of the world” (p. 7). Emphasizing the connection between theory and practice, postcolonial intellectuals consider themselves critical thinkers challenging the alleged superiority of Western cultures, racism and other forms of ethnic bias, economic inequality separating the Global North from the South, and the persistence of “Orientalism”—a discriminatory, Europe-derived mindset so brilliantly dissected by late postcolonial theorist Edward Said (1979) .

A number of postcolonial and indigenous theorists have examined the connections between globalization and postcolonialism (Krishna 2009) . While most have expressed both their appreciation and their affinity for much of what GS stands for, they have also offered incisive critiques of what they view as the field’s troubling geographic, ethnic, and epistemic location within the hegemonic Western framework. The noted ethnic studies scholar Ramón Grosfoguel (2005: 284) , for example, offers a clear and comprehensive summary of such postcolonial concerns: “Globalization studies, with a few exceptions, have not derived the epistemological and theoretical implications of the epistemic critique coming from subaltern locations in the colonial divide and . . . continue to produce a knowledge from the Western man ‘point zero’ god’s-eye view.”

Such postcolonial criticisms of GS provide an invaluable service by highlighting some remaining conceptual parochialisms behind its allegedly “global” theoretical and practical concerns. Indeed, their intervention suggests that GS thinkers have not paid enough attention to the postcolonial imperative of contesting the dominant Western ways of seeing and knowing. Thus, they force scholars working in the field to confront crucial questions that are often relegated to the margins of intellectual inquiry. Is critical theory sufficiently global to represent the diverse voices of the multitude and speak to the diverse experiences of disempowered people throughout the world? What sort of new and innovative ideas have been produced by public intellectuals who do not necessarily travel along the theoretical and geographical paths frequented by Western critical thinkers? Are there pressing issues and promising intellectual approaches that have been neglected in CGS? These questions also relate to the central role of the English language in GS. With English expanding its status as the academic lingua franca, thinkers embedded in Western universities still hold the monopoly on the production of critical theories. Important contributions from the Global South in languages other than English often fall through the cracks or only register in translated form on the radar of the supposedly “global” academic publishing network years after their original publication.

As noted in the previous discussion of the fourth pillar of GS, however, it is essential to acknowledge the progress that has been made in GS to expand its “space of tension” by welcoming and incorporating Global South perspectives. As early as 2005, for example, a quarter of the contributions featured in Appelbaum and Robinson’s (2005) Critical Globalization Studies anthology came from authors located in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Since then, pertinent criticisms from within that demanded the inclusion of multiple voices and perspectives from throughout the world have proliferated. Consider, for example, Eve Darian-Smith’s (2015) recent critique of taken-for-granted assumptions on the part of Western scholars to speak for others in the Global South. Moreover, scores of public intellectuals hailing from the Global South have not only produced influential studies on globalization but also stood in solidarity with movement activists struggling against the forces of globalization-from-above. 6 As demonstrated by the diversity of views and perspectives represented in this volume, many GS scholars are paying attention to these important postcolonial interventions. Still, there is still plenty of room for further improvement.

Let me end this chapter with a bit of speculation about the future of GS. Perhaps its most pressing task for the next decade is to keep chipping away at the disciplinary walls that still divide the academic landscape Animated by an ethical imperative to globalize knowledge, such transdisciplinary efforts have the potential to reconfigure our discipline-oriented academic infrastructure around issues of global public responsibility ( Kennedy 2015 : xv). This integrative endeavor must be undertaken steadily and tirelessly—but also carefully and with the proper understanding that diverse and multiple forms of knowledge are sorely needed to educate a global public. The necessary appreciation for the interplay between specialists and generalists must contain a proper respect for the crucial contributions of the conventional disciplines to our growing understanding of globalization. But the time has come to take the next step.

Further Reading

Anheier, Helmut K. , and Mark Juergensmeyer , editors. 2012 . Encyclopedia of Global Studies . 4 vols. London: Sage.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Campbell, Patricia J. , Aran MacKinnon , and Christy R. Stevens . 2010 . Introduction to Global Studies . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Juergensmeyer, Mark , ed. 2014 . Thinking Globally: A Global Studies Reader . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Smallman, Shawn C. , and Kimberely Brown . 2015 . Introduction to International and Global Studies. 2nd ed. Raleigh: University of North Carolina Press.

Steger, Manfred B. , ed. 2014 . The Global Studies Reader. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Steger, Manfred B. , and Paul James , ed. 2015 . Globalization: The Career of a Concept . London and New York: Routledge.

Steger, Manfred B. , and Amentahru Wahlrab . 2016 . What Is Global Studies? Theory & Practice. New York: Routledge.

Thus, GS is closer to social constructivism in IR, which deconstructs the unitary actor model of the state in favor of a more complex conception that emphasizes an amalgam of interests, identities, and contingency.

For a book-length treatment of this question, see Steger and Wahlrab (2016) . This chapter contains the principal arguments of the book in compressed form.