Freedom's Ring "I Have a Dream" Speech

Main navigation.

Freedom's Ring is Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, annotated. Here you can compare the written and spoken speech, explore multimedia images, listen to movement activists and uncover historical context.

Fifty years ago, in the concluding address of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, King demanded the riches of freedom and the security of justice. Today his language of love, nonviolent direct action and redemptive suffering, resonates globally in the millions who stand up for freedom and elevate democracy to its ideals. How do the echoes of King's Dream live within you?

Freedom's Ring serves as an innovative and thought-provoking resource for teachers, students, and the larger community. Evan Bissell, a Bay Area artist and educator, and webdesigner Erik Loyer worked with King Institute's Dr. Andrea McEvoy Spero, Dr. Clayborne Carson and Regina Covington to create an engaging experience that documents one of the most famous events in Civil Rights history. Freedom's Ring compliments the King Legacy Series by Beacon Press and the corresponding curriculum guide.

Freedom’s Ring

King’s “i have a dream” speech.

Freedom’s Ring is Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, animated. Here you can compare the written and spoken speech, explore multimedia images, listen to movement activists, and uncover historical context. Fifty years ago, as the culminating address of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, King demanded the riches of freedom and the security of justice. Today, his language of love, nonviolent direct action, and redemptive suffering resonates globally in the millions who stand up for freedom together and elevate democracy to its ideals. How do the echoes of King’s Dream live within you?

Credits & Acknowledgements

Director, Art and Content: Evan Bissell Design and Programming: Erik Loyer Content, Curriculum Design and Project Coordinator: Andrea McEvoy Spero Project Advisor: Clayborne Carson Video: Owen Bissell Project Administration: Regina Covington

Freedom’s Ring is a project of The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in collaboration with Beacon Press’s King Legacy Series.

We extend our deep appreciation to the many people whose work and lives contributed to Freedom’s Ring. Thank you to the interviewees: Aldo Billingslea, Clayborne Carson, Dorothy Cotton, Miriam Glickman, Kazu Haga, Bruce Hartford, Ericka Huggins, Clarence B. Jones, Kim Nalley, Wazir Peacock, and Marcus Shelby.

Thank you to Tenisha Armstrong. Her dedication and tireless efforts in editing Dr. King’s papers allow us to make this history available to teachers and students.

Thank you to the many photographers whose work has inspired much of this project and allowed these important histories to continue. We have made our best efforts to credit these photographers. They include: Bob Adelman, Eve Arnold, George Ballis, Martha Cooper, Benedict Fernandez, Bob Fitch, Declan Haun, Matt Herron, John Loengard, Danny Lyon, Spider Martin, Charles Moore/Black Star, Herbert Randall, Steve Schapiro, Flip Schulke, Maria Varela, and Tamio Wakayama.

Thank you to David Stein for his invaluable contributions and conversations about this history. Thanks to Lucas Guilkey for his work on the videos, Ming-kuo Hung for editing support, and Naomi Wilson for her comments on content.

Thanks to Beacon Press for editing support.

Thanks to Headlands Center for the Arts for the time and space to finish the project.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute Staff:

Clayborne Carson Director

Tenisha Armstrong Associate Director and Editor of the King Papers Project

Regina Covington Administrator

Andrea McEvoy Spero Director of Education

Clarence B. Jones Scholar in Residence

Susan Carson Editorial Consultant

Stacey Zwald Assistant Editor

Dave Beals Research Assistant

Video hosting by Critical Commons Content management by Scalar , a project of the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture

Works Cited

Baldwin, James. The Fire Next Time. New York: Dell, 1985. Print.

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King years, 1954-63. New York : Simon and Schuster, 1988. Print.

Carson, Clayborne, eds. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.. New York: Intellectual Properties Management; Warner Books, 1998. Print.

Freed, Leonard. This Is the Day: The March on Washington. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013. Print.

Hansen, Drew D.. The Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York : Ecco. 2003. Print.

Johnson, Charles and Bob Adelman. King: The Photobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York : Viking, 2000. Print.

Jones, Clarence B. and Stuart Connelly. Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print.

Jones, William P.. The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights. New York : W.W. Norton, 2013. Print.

Jones, William P. and Labor and Working-Class History Association. “The Unknown Origins of the March on Washington: Civil Rights Politics and the Black Working Class.” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 7.3 (2010). Print.

Kasher, Steven. The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, 1954-68. New York: Abbeville, 1996. Print.

Katznelson, Ira. Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time. New York: Liveright, 2013. Print.

Kelen, Leslie G., eds. This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement. Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2011. Print.

LaFayette, Jr., Bernard and David C. Jehnsen. The Nonviolence Briefing Booklet: A 2-Day Orientation to Kingian Nonviolence Conflict Reconciliation. 1995. Galena: Institute for Human Rights and Responsibilities. 2007. Print.

Le Blanc, Paul. “Freedom Budget: The Promise of the Civil Rights Movement for Economic Justice.” WorkingUSA: The Journal of Labor & Society 16 (2013), 43-58. Print.

Levine, Ellen. Freedom's Children : Young Civil Rights Activists Tell Their Own Stories. New York : Putnam, 1993. Print.

Lewis, John and Michael D’Orso. Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998. Print.

Sundquist, Eric J.. King’s Dream. New Haven : Yale University, 2009. Print.

Scroll position

The 1963 March on Washington

A quarter million people and a dream.

On August 28, 1963, more than a quarter million people participated in the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, gathering near the Lincoln Memorial.

More than 3,000 members of the press covered this historic march, where Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the exalted "I Have a Dream" speech.

Originally conceived by renowned labor leader A. Phillip Randolph and Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, the March on Washington evolved into a collaborative effort amongst major civil rights groups and icons of the day.

Stemming from a rapidly growing tide of grassroots support and outrage over the nation's racial inequities, the rally drew over 260,000 people from across the nation.

Celebrated as one of the greatest — if not the greatest — speech of the 20th century, Dr. King's celebrated speech, "I Have a Dream," was carried live by television stations across the country. You can read the full speech and watch a short film, below.

A March 20 Years in the Making

In 1941, A. Phillip Randolph first conceptualized a "march for jobs" in protest of the racial discrimination against African Americans from jobs created by WWII and the New Deal programs created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The march was stalled, however, after negotiations between Roosevelt and Randolph prompted the establishment of the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) and an executive order banning discrimination in defense industries.

The FEPC dissolved just five years later, causing Randolph to revive his plans. He looked to the charismatic Dr. King to breathe new life into the march.

NAACP and SCLC Center the March on Civil Rights

By the late 1950s, Dr. King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were also planning to march on Washington, this time to march for freedom.

As the years passed on, the Civil Rights Act was still stalled in Congress, and equality for Americans of color still seemed like a far-fetched dream.

Randolph, his chief aide, Bayard Rustin, and Dr. King all decided it would be best to combine the two causes into one mega-march, the March for Jobs and Freedom.

NAACP, headed by Roy Wilkins, was called upon to be one of the leaders of the march.

As one of the largest and most influential civil rights groups at the time, our organization harnessed the collective power of its members, organizing a march that was focused on the advancement of civil rights and the actualization of Dr. King's dream.

The Big Six

A quarter-million people strong, the march drew activists from far and wide.

Leaders of the six prominent civil rights groups at the time joined forces in organizing the march.

The group included Randolph, leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP; Dr. King, Chairman of the SCLC; James Farmer, founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); John Lewis, President of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); and Whitney Young, Executive Director of the National Urban League.

Dr. King, originally slated to speak for 4 minutes, went on to speak for 16 minutes, giving one of the most iconic speeches in history.

"I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood." – I Have a Dream, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

It didn't take long for King's dream to come to fruition — the legislative aspect of the dream, that is.

After a decade of continued lobbying of Congress and the President led by the NAACP, plus other peaceful protests for civil rights, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

One year later, he signed the National Voting Rights Act of 1965 .

Together, these laws outlawed discrimination against blacks and women, effectively ending segregation, and sought to end disenfranchisement by making discriminatory voting practices illegal.

Ten years after King joined the civil rights fight, the campaign to secure the enactment of the 1964 Civil Rights Act had achieved its goal – to ensure that black citizens would have the power to represent themselves in government.

2020 March on Washington

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered this iconic 'I Have a Dream' speech at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. See entire text of King's speech below.

I Have a Dream

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free; one hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination; one hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity; one hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.

So we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was the promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note in so far as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked "insufficient funds."

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we have come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now.

This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy; now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice; now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood; now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment.

This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content, will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people, who stand on the worn threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protests to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy, which has engulfed the Negro community, must not lead us to a distrust of all white people. For many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of Civil Rights, "When will you be satisfied?"

We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality; we can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities; we cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one; we can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating "For Whites Only"; we cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro in Mississippi cannot vote, and the Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No! no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until "justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream."

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality.

You have been the veterans of creative suffering.

Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi. Go back to Alabama. Go back to South Carolina. Go back to Georgia. Go back to Louisiana. Go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.

It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama — with its vicious racists, with its Governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification — one day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low. The rough places will be plain and the crooked places will be made straight, "and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together."

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.

With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brother-hood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning, "My country 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my father died, land of the pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring." And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire; let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York; let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania; let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado; let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that.

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia; let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee; let freedom ring from every hill and mole hill of Mississippi. "From every mountainside, let freedom ring."

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

"Free at last. Free at last. Thank God Almighty, we are free at last."

Source: Martin Luther King, Jr., I Have A Dream: Writings and Speeches that Changed the World (San Francisco: Harper, 1986) via Teaching America History.

Meet other heroes who advanced racial justice

The voices of these visionaries shape our present and inform our future.

Join the fight

You are critical to the hard, complex work of ending racial inequality.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Martin Luther King Jr.

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 25, 2024 | Original: November 9, 2009

Martin Luther King Jr. was a social activist and Baptist minister who played a key role in the American civil rights movement from the mid-1950s until his assassination in 1968. King sought equality and human rights for African Americans, the economically disadvantaged and all victims of injustice through peaceful protest. He was the driving force behind watershed events such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the 1963 March on Washington , which helped bring about such landmark legislation as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act . King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and is remembered each year on Martin Luther King Jr. Day , a U.S. federal holiday since 1986.

When Was Martin Luther King Born?

Martin Luther King Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia , the second child of Martin Luther King Sr., a pastor, and Alberta Williams King, a former schoolteacher.

Along with his older sister Christine and younger brother Alfred Daniel Williams, he grew up in the city’s Sweet Auburn neighborhood, then home to some of the most prominent and prosperous African Americans in the country.

Did you know? The final section of Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech is believed to have been largely improvised.

A gifted student, King attended segregated public schools and at the age of 15 was admitted to Morehouse College , the alma mater of both his father and maternal grandfather, where he studied medicine and law.

Although he had not intended to follow in his father’s footsteps by joining the ministry, he changed his mind under the mentorship of Morehouse’s president, Dr. Benjamin Mays, an influential theologian and outspoken advocate for racial equality. After graduating in 1948, King entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, where he earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree, won a prestigious fellowship and was elected president of his predominantly white senior class.

King then enrolled in a graduate program at Boston University, completing his coursework in 1953 and earning a doctorate in systematic theology two years later. While in Boston he met Coretta Scott, a young singer from Alabama who was studying at the New England Conservatory of Music . The couple wed in 1953 and settled in Montgomery, Alabama, where King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church .

The Kings had four children: Yolanda Denise King, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott King and Bernice Albertine King.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

The King family had been living in Montgomery for less than a year when the highly segregated city became the epicenter of the burgeoning struggle for civil rights in America, galvanized by the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks , secretary of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ), refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery bus and was arrested. Activists coordinated a bus boycott that would continue for 381 days. The Montgomery Bus Boycott placed a severe economic strain on the public transit system and downtown business owners. They chose Martin Luther King Jr. as the protest’s leader and official spokesman.

By the time the Supreme Court ruled segregated seating on public buses unconstitutional in November 1956, King—heavily influenced by Mahatma Gandhi and the activist Bayard Rustin —had entered the national spotlight as an inspirational proponent of organized, nonviolent resistance.

King had also become a target for white supremacists, who firebombed his family home that January.

On September 20, 1958, Izola Ware Curry walked into a Harlem department store where King was signing books and asked, “Are you Martin Luther King?” When he replied “yes,” she stabbed him in the chest with a knife. King survived, and the attempted assassination only reinforced his dedication to nonviolence: “The experience of these last few days has deepened my faith in the relevance of the spirit of nonviolence if necessary social change is peacefully to take place.”

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

Emboldened by the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, in 1957 he and other civil rights activists—most of them fellow ministers—founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a group committed to achieving full equality for African Americans through nonviolent protest.

The SCLC motto was “Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed.” King would remain at the helm of this influential organization until his death.

In his role as SCLC president, Martin Luther King Jr. traveled across the country and around the world, giving lectures on nonviolent protest and civil rights as well as meeting with religious figures, activists and political leaders.

During a month-long trip to India in 1959, he had the opportunity to meet family members and followers of Gandhi, the man he described in his autobiography as “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change.” King also authored several books and articles during this time.

Letter from Birmingham Jail

In 1960 King and his family moved to Atlanta, his native city, where he joined his father as co-pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church . This new position did not stop King and his SCLC colleagues from becoming key players in many of the most significant civil rights battles of the 1960s.

Their philosophy of nonviolence was put to a particularly severe test during the Birmingham campaign of 1963, in which activists used a boycott, sit-ins and marches to protest segregation, unfair hiring practices and other injustices in one of America’s most racially divided cities.

Arrested for his involvement on April 12, King penned the civil rights manifesto known as the “ Letter from Birmingham Jail ,” an eloquent defense of civil disobedience addressed to a group of white clergymen who had criticized his tactics.

March on Washington

Later that year, Martin Luther King Jr. worked with a number of civil rights and religious groups to organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a peaceful political rally designed to shed light on the injustices Black Americans continued to face across the country.

Held on August 28 and attended by some 200,000 to 300,000 participants, the event is widely regarded as a watershed moment in the history of the American civil rights movement and a factor in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .

"I Have a Dream" Speech

The March on Washington culminated in King’s most famous address, known as the “I Have a Dream” speech, a spirited call for peace and equality that many consider a masterpiece of rhetoric.

Standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial —a monument to the president who a century earlier had brought down the institution of slavery in the United States—he shared his vision of a future in which “this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'”

The speech and march cemented King’s reputation at home and abroad; later that year he was named “Man of the Year” by TIME magazine and in 1964 became, at the time, the youngest person ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize .

In the spring of 1965, King’s elevated profile drew international attention to the violence that erupted between white segregationists and peaceful demonstrators in Selma, Alabama, where the SCLC and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had organized a voter registration campaign.

Captured on television, the brutal scene outraged many Americans and inspired supporters from across the country to gather in Alabama and take part in the Selma to Montgomery march led by King and supported by President Lyndon B. Johnson , who sent in federal troops to keep the peace.

That August, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act , which guaranteed the right to vote—first awarded by the 15th Amendment—to all African Americans.

Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

The events in Selma deepened a growing rift between Martin Luther King Jr. and young radicals who repudiated his nonviolent methods and commitment to working within the established political framework.

As more militant Black leaders such as Stokely Carmichael rose to prominence, King broadened the scope of his activism to address issues such as the Vietnam War and poverty among Americans of all races. In 1967, King and the SCLC embarked on an ambitious program known as the Poor People’s Campaign, which was to include a massive march on the capital.

On the evening of April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated . He was fatally shot while standing on the balcony of a motel in Memphis, where King had traveled to support a sanitation workers’ strike. In the wake of his death, a wave of riots swept major cities across the country, while President Johnson declared a national day of mourning.

James Earl Ray , an escaped convict and known racist, pleaded guilty to the murder and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. He later recanted his confession and gained some unlikely advocates, including members of the King family, before his death in 1998.

After years of campaigning by activists, members of Congress and Coretta Scott King, among others, in 1983 President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a U.S. federal holiday in honor of King.

Observed on the third Monday of January, Martin Luther King Day was first celebrated in 1986.

Martin Luther King Jr. Quotes

While his “I Have a Dream” speech is the most well-known piece of his writing, Martin Luther King Jr. was the author of multiple books, include “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story,” “Why We Can’t Wait,” “Strength to Love,” “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?” and the posthumously published “Trumpet of Conscience” with a foreword by Coretta Scott King. Here are some of the most famous Martin Luther King Jr. quotes:

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

“Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

“The time is always right to do what is right.”

"True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice."

“Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

“Free at last, Free at last, Thank God almighty we are free at last.”

“Faith is taking the first step even when you don't see the whole staircase.”

“In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”

"I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant."

“I have decided to stick with love. Hate is too great a burden to bear.”

“Be a bush if you can't be a tree. If you can't be a highway, just be a trail. If you can't be a sun, be a star. For it isn't by size that you win or fail. Be the best of whatever you are.”

“Life's most persistent and urgent question is, 'What are you doing for others?’”

Photo Galleries

HISTORY Vault: Voices of Civil Rights

A look at one of the defining social movements in U.S. history, told through the personal stories of men, women and children who lived through it.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Black History Month 2024

5 mlk speeches you should know. spoiler: 'i have a dream' isn't on the list.

Scott Neuman

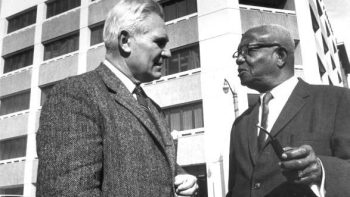

The Rev. Ralph Abernathy (left) shakes hands with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery, Ala., on March 22, 1956, as a big crowd of supporters cheers for King, who had just been found guilty of leading the Montgomery bus boycott. Gene Herrick/AP hide caption

The Rev. Ralph Abernathy (left) shakes hands with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery, Ala., on March 22, 1956, as a big crowd of supporters cheers for King, who had just been found guilty of leading the Montgomery bus boycott.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s " I Have a Dream " speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, is so famous that it often eclipses his other speeches.

King's greatest contribution to the Civil Rights Movement was his oratory, says Jason Miller, an English professor at North Carolina State University who has written extensively on King's speeches.

Black History Month 2024 has begun. Here's this year's theme and other things to know

"King's first biographer was a dear friend of Dr. King's, L.D. Reddick ," Miller says. Reddick once suggested to King that maybe more marching and less speaking was needed to push the cause of civil rights forward. According to Miller, King is said to have responded, "My dear man, you never deny an artist his medium."

Miller says that in his research, he found numerous examples of King reworking and recycling old speeches. "He would rewrite them ... just to change phrasings and rhythms. And so he prepared a great deal, often 19 lines per page on a yellow legal sheet."

Often, King would write notes to himself in the margins: "what tenor and tone to deliver," Miller says.

That phrasing and an understanding of cadence were all important to the success of these speeches, according to Carolyn Calloway-Thomas, director of graduate studies at the Department of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Indiana University.

King's training in the pulpit gave him a strong insight into what moves an audience, she says. "Preachers are performers. They know when to pause. How long to pause. And with what effect. And he certainly was a great user of dramatic pauses."

Here are four of King's speeches that sometimes get overlooked, plus the one he delivered the day before his 1968 assassination. Collectively, they represent historical signposts on the road to civil rights.

" Give Us the Ballot " (May 17, 1957 — Washington, D.C.)

King spoke at the Lincoln Memorial three years to the day after the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education , which struck down the "separate but equal" doctrine that had allowed segregation in public schools.

But Jim Crow persisted throughout much of the South. The yearlong Montgomery bus boycott , sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks, had ended only months before King's speech. And the Voting Rights Act of 1965 , which sought to end disenfranchisement of Black voters, was still eight years away.

"It's a very important speech because he's talking about the importance of voting and he's responding to some of the Southern resistance to the Brown decision," says Vicki Crawford, director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Collection at Morehouse College, King's alma mater .

U.S. deputy marshals escort 6-year-old Ruby Bridges from William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans in November 1960. The first-grader was the only Black child enrolled in the school, where parents of white students were boycotting the court-ordered integration law and were taking their children out of school. AP hide caption

U.S. deputy marshals escort 6-year-old Ruby Bridges from William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans in November 1960. The first-grader was the only Black child enrolled in the school, where parents of white students were boycotting the court-ordered integration law and were taking their children out of school.

The speech calls out both major political parties for betraying "the cause of justice" and failing to do enough to ensure civil rights for Blacks. He accuses Democrats of "capitulating to the prejudices and undemocratic practices of the Southern Dixiecrats," referring to the party's pro-segregation wing. The Republicans, King said, had instead capitulated "to the blatant hypocrisy of right-wing, reactionary Northerners."

King speaks at a mass demonstration at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., on May 17, 1957, as civil rights leaders called on the U.S. government to put more teeth into the Supreme Court's desegregation decisions. Charles Gorry/AP hide caption

King speaks at a mass demonstration at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., on May 17, 1957, as civil rights leaders called on the U.S. government to put more teeth into the Supreme Court's desegregation decisions.

He also indicts Northern liberals who are "so bent on seeing all sides" that they are "neither hot nor cold, but lukewarm" in their commitment to civil rights.

"King [was] calling on both parties to take a look at themselves," Crawford says.

With the movement gaining steam, King used his speech to take stock of where things stood and what must be done next, Calloway-Thomas says. "He is revisiting the status of African American people."

" Our God Is Marching On! " (March 25, 1965 — Montgomery, Ala.)

The speech was delivered after the last of three Selma-Montgomery marches to call for voting rights. Protesters were beaten by Alabama law enforcement officials at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on March 7 in what came to be known as Bloody Sunday . Among the nearly 60 wounded that day by club-wielding police was John Lewis, the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who suffered a fractured skull. (Lewis later served 17 terms in the U.S. House of Representatives.) A second attempt to reach Montgomery a few days later was again turned back at the bridge. In a third try, marchers finally reached the steps of the Alabama State Capitol on March 25.

Rep. John Lewis, A Force In The Civil Rights Movement, Dead At 80

"Finally the group of protesters gets all the way to the Capitol, and King delivers a speech to what we think is about 25,000 people," Miller says. The speech is also often referred to as the "How Long? Not Long" speech because of that powerful refrain, Miller says.

Jonathan Eig, author of the biography King: A Life , published last year, says he thinks about three-fourths of the speech was written out. "Then [King] goes off script and gives a sermon."

That's when he answers the question "How long?" for his audience. How long will it be until Black people have the same rights as white people? "Not long, because no lie can live forever," King tells his exuberant listeners.

"That's the part that really echoes. No question," Eig says. "And I think that's when he knew he was at his best. He knew that he could bring the crowd to its feet and inspire them."

Also notable is a famous anecdote that King shared in his speech, one that appeared earlier in his 1963 " Letter from a Birmingham Jail " addressed to his "fellow clergymen." It relates the words of Sister Pollard, a 70-year-old Black woman who had walked everywhere, refusing to ride the Montgomery buses during the 1955-1956 boycott.

"One day, she was asked while walking if she didn't want to ride," King said, speaking to the crowd that had just successfully marched from Selma to Montgomery. "And when she answered, 'No,' the person said, 'Well, aren't you tired?' And with her ungrammatical profundity, she said, 'My feets is tired, but my soul is rested.'"

"And in a real sense this afternoon, we can say that our feet are tired but our souls are rested," he said.

The story of Sister Pollard would be used again in the coming years.

But the speech may be best remembered today for another line, where King said, "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."

In fact, King was using the words of a 19th-century Unitarian minister, Theodore Parker . Parker was an abolitionist who secretly funded John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, often seen as an opening salvo of the Civil War. In a sermon given seven years before the raid, Parker used the line that King would pick up more than a century later.

"Dr. King absorbed all kinds of material, heard from others, used it on his own. But this is what we call appropriation or transformation when the old seems new," Miller says.

" Beyond Vietnam " (April 4, 1967 — New York City)

King had already begun speaking out about the war in Vietnam, but this speech was his most forceful statement on the conflict to date. Black soldiers were dying in disproportionate numbers . King noted the irony that in Vietnam, "Negro and white boys" were killing and dying alongside each other "for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools."

"So we watch them, in brutal solidarity, burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago," he said. "I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor."

An infantry soldier runs across a burned-out clearing in Vietnam on Jan. 4, 1967. Horst Faas/AP hide caption

An infantry soldier runs across a burned-out clearing in Vietnam on Jan. 4, 1967.

SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael , a major civil rights figure, had come out against the war and encouraged King to join him. But some in King's own inner circle had cautioned him against speaking about Vietnam.

Code Switch

Stokely carmichael, a philosopher behind the black power movement.

Although powerful and timely, the speech drew a harsh and immediate reaction from a nation that had only just begun to reckon with the rising casualties and economic toll of the war. Both The Washington Post and The New York Times published editorials criticizing it. The Post said King had "diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people" and the Times said he had "dampened his prospects for becoming the Negro leader who might be able to get the nation 'moving again' on civil rights."

King knew he would take heat for the speech, especially from the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, with whom he'd worked to get the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and, a year later, the Voting Rights Act, through Congress. With the presidential election just 19 months away, continued support of Johnson's Vietnam policy was crucial to his reelection. Nearly 10 months after the speech, however, the Tet Offensive launched by the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese army would help turn U.S. public opinion against the war and lead Johnson to not seek another term.

But in April 1967, the reaction to the speech was "far worse than King or his advisers imagined," says Miller, of North Carolina State University. Johnson "excommunicated" the civil rights leader, he says, adding that even leaders of the NAACP expressed disappointment that King had focused attention on the war.

"His immediate response was that he was crushed," Miller says. "There are a number of people who have documented that he literally broke down in tears when he realized the kind of backlash towards it."

He was criticized from both sides of the political aisle. Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., a staunch conservative who made a failed run for the presidency in 1964, said King's speech "could border a bit on treason."

"King himself said that he anguished over doing the speech," says Indiana University's Calloway-Thomas.

" The Three Evils of Society " (Aug. 31, 1967 — Chicago)

The three evils King outlines in this speech are poverty, racism and militarism . Referring to Johnson's Great Society program to help lift rural Americans out of poverty, King said that it had been "shipwrecked off the coast of Asia, on the dreadful peninsula of Vietnam" and that meanwhile, "the poor, Black and white are still perishing on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity."

Calloway-Thomas calls it "the most scathing critique of American society by King that I have ever read."

"We need, according to him, a radical redistribution of political and economic power," she says, "Is that implying reparations? Is that implying socialism?"

Calloway-Thomas hears in King's words an antecedent to the Black Lives Matter movement. "One sees in that speech some relationship between the rhetoric of Dr. King at that moment and the rhetoric of Black Lives Matter at this moment," she says.

It was also one of the many instances where King quoted poet Langston Hughes, with whom he had become friends. "What happens to a dream deferred? It leads to bewildering frustration and corroding bitterness," King said in a nod to Hughes' most famous poem, " Harlem ."

King and Hughes traveled together to Nigeria in 1960, Miller notes, calling the poet an often unrecognized but nonetheless "central figure" in the early Civil Rights Movement. "They exchanged letters. Dr. King told [Hughes] how much he used his poetry. Dr. King used seven poems by Langston Hughes in his sermons and speeches from 1956 to 1958."

" I've Been to the Mountaintop! " (April 3, 1968 — Memphis, Tenn.)

This is King's last speech, delivered a day before his assassination at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., on April 4, 1968. He was in the city to lend his support and his voice to the city's striking sanitation workers .

"He wasn't expecting to give a speech that night," according to Clayborne Carson, Martin Luther King, Jr. centennial professor emeritus at Stanford University. "He was hoping to get out of it. He was not feeling well."

"They call him and say, 'The people here want to hear you. They don't want to hear us.' And plus, the place was packed that night" despite a heavy downpour, Carson says. "I think he recognized that people really wanted to hear him. And despite the state of his health, he decided to go."

Martin Luther King Jr. makes his last public appearance, at the Mason Temple in Memphis, Tenn., on April 3, 1968. The following day, King was assassinated on his motel balcony. Charles Kelly/AP hide caption

Martin Luther King Jr. makes his last public appearance, at the Mason Temple in Memphis, Tenn., on April 3, 1968. The following day, King was assassinated on his motel balcony.

The haunting words, in which King says, "I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you" have led many people to think he was prophesying his own death the following day at the hands of assassin James Earl Ray .

"The speech really does feel a bit like his own eulogy," says Eig. "He's talking about earthly salvation and heavenly salvation. And, in the end, boldly equating himself with Moses, who doesn't live to see the Promised Land."

The speech is largely, if not entirely, extemporaneous. And by the end, King was exhausted, says Carson. "It's pretty clear when you watch the film that he's not in the best shape."

"He barely makes it to the end," he says.

"But he relied on his audience to bring him along," Carson says. "I think it's one of those speeches where the crowd is inspiring him and he's inspiring them. That's what makes it work."

It's a great speech, made greater still because it was his last, says Calloway-Thomas.

"You have this wonderful man who epitomized the social and political situation in the United States in the 20th century," she says. "There he is, dying so tragically and dreadfully. It has a lot of pity and pathos buried inside it."

- Black History Month

- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

- Civil Rights Movement

- Black History

4 Powerful Martin Luther King, Jr. Speeches That Aren’t ‘I Have A Dream’

Rev › Blog › Transcription Blog › 4 Powerful Martin Luther King, Jr. Speeches That Aren’t ‘I Have A Dream’

Today we honor the great life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. who was a revolutionary civil rights leader and minister. Dr. King ’s work to eradicate racial segregation was abruptly halted when he was assassinated on April 4, 1968, on the balcony of Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. While his legacy is commonly remembered by his famous “I Have A Dream” speech, we’ve sourced four powerful, lesser-known speeches from Dr. King to listen to and commemorate his legacy.

Beyond Vietnam: “A Time to Break Silence”

Many Americans saw the U.S. engagement in a conflict thousands of miles away as pointless, especially one that caused so much damage at home and abroad.

It was in the midst of anti-Vietnam protests that Martin Luther King Jr. delivered “A Time to Break Silence.” King’s speech effectively confronts both of these issues: civil rights and opposition to the Vietnam War.

Key quotes:

( 33:24 ) “Each day the war goes, on the hatred increases in the heart of the Vietnamese and in the hearts of those of humanitarian instinct. The Americans are forcing even their friends into becoming their enemies. It is curious that the Americans, who calculate so carefully on the possibilities of military victory, do not realize that in the process they are incurring deep psychological and political defeat. The image of America will never again be the image of revolution, freedom, and democracy, but the image of violence and militarism.”

( 50:12 ) “We still have a choice today: nonviolent coexistence or violent coannihilation. We must move past indecision to action. We must find new ways to speak for peace in Vietnam and justice throughout the developing world, a world that borders on our doors.”

“The American Dream”

King also underscores the dignity of all work, proclaiming that even menial workers should earn enough “so they can live and educate their children and buy a home and have the basic necessities of life.”

( 06:03 ) “It is trite, but urgently true that if America is to remain a first-class nation, she can no longer have second-class citizens. I must rush on to say that we must not seek to solve this problem merely to meet the communist challenge. We must not seek to do it merely to appeal to Asian and African people. In the final analysis, racial discrimination must be uprooted from our society because it is morally wrong.

( 23:07 ) Human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and the persistent work of dedicated individuals. And without this hard work, time itself becomes the ally of the insurgent and primitive forces of irrational emotionalism and social stagnation, so that we must somehow get rid of this idea that time alone with solve the problem. We must use time.

“Our God Is Marching On!”

King’s on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol, near the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where he’s launched the Montgomery bus boycott. Meanwhile, Alabama Gov. George Wallace cowers in his office with blinds drawn.

When the enthusiastic crowd joins King in chanting “Glory hallelujah!” at the end of his speech, the march transforms into a roaring church revival.

The Selma campaign would spark the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Key quotes: “Yes, we are on the move and no wave of racism can stop us. The burning of our churches will not deter us. The bombing of our homes will not dissuade us. The beating and killing of our clergymen and young people will not divert us.”

“I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because ‘truth crushed to earth will rise again.’ How long? Not long! Because ‘no lie can live forever.’ How long? Not long! Because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

I Have Been to the Mountaintop

The Black sanitation workers of Memphis, exhausted from battling a stubborn city administration for improved employment conditions, called in the cavalry: Dr. King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

“We’ve got some difficult days ahead,” King told an energized crowd in Memphis, Tennessee, where the city’s sanitation workers were striking. “But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop … I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

Reflecting on his own mortality, King appeared to prophesize his death, as he was assassinated the following day. Though his speech was about so much more than King’s life and fate;

It was an emphatic call to action for economic justice in America, a call that continues to be relevant today.

( 09:16 ) “We mean business now and we are determined to gain our rightful place in God’s world. And that’s all this whole thing is about. We aren’t engaged in any negative protest and in any negative arguments with anybody. We are saying that we are determined to be men. We are determined to be people. We are saying, that we are God’s children. And if we are God’s children, we don’t have to live like we are forced to live.”

( 28:01 ) “Now let me say as I move to my conclusion that we’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through. And when we have our march, you need to be there. If it means leaving work, if it means leaving school, be there. Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike, but either we go up together or we go down together. Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness.”

( 42:03 ) “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life – longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will.”

Everybody’s Favorite Speech-to-Text Blog

We combine AI and a huge community of freelancers to make speech-to-text greatness every day. Wanna hear more about it?

- Back to School

- Decision 2024

- Pittsburgh Gets Real

- Clark Howard (Opens in new window)

- Weather App

- Interactive Radar

- Hour by Hour

- 5 Day Forecast

- WPXI 24/7 News

- WPXI Weather 24/7

- The $pend $mart Stream

- Law & Crime

- Curiosity NOW

- 11 Investigates

- The Final Word

- 11 on the Ice

- Jerome Bettis Show

- Steals and Deals

- Home Experts

- Care Connect

- Breaking the Stigma

- Advertise With WPXI

- Live Traffic Updates

- What's on WPXI

- Lottery Results

- Laff (Opens in new window)

- ME-TV (Opens in new window)

- Share Your Pics!

- Closed Captioning

- Internships

- Jobs at WPXI (Opens in new window)

- Our Region's Business

- UPMC: Community Matters

- UPMC: Minutes Matter

- Chiller Theater

- Visitor Agreement

- Privacy Policy

Martin Luther King Jr.: How the world heard the news of his assassination

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. FILEPHOTO: Caught in a somber mood, Dr. Martin Luther King addresses some 2,000 people on the eve of his death, giving the speech "I've been to the mountaintop." The former founder and Chairman of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference was slain by James Earl Ray on April 4, 1968. (Bettmann/Bettmann Archive)

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in 2018 for the 50th anniversary of the Martin Luther King Jr. assassination.

April 4 marks the anniversary of the day Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee.

>> Read more trending news

King, the leader of the non-violent movement for civil rights in the 1960s, had come to Memphis the day before to help sanitation workers rally for better wages and safer working conditions.

That evening, as King stood on a balcony at the Lorraine Motel, he was mortally wounded by a bullet from a rifle believed to have been fired from a rooming house across the street from the Lorraine. King was hit in the jaw and knocked unconscious. He was pronounced dead at the St. Joseph’s Hospital about an hour later, having never regained consciousness.

Here is how the world learned and reacted to the news of King’s assassination:

What King said night before he was murdered:

King came to Memphis in early April 1968 to help striking sanitation workers in their protests for better wages and safer working conditions. On April 3, King addressed a gathering at the Mason Temple in Memphis. He said he did not feel well and did not want to go, but went anyway on the urging of his aides. King stood before the crowd and spoke extemporaneously for more than 40 minutes. The speech turned out to be prophetic, as King told those gathered he had “been to the mountaintop,” but that he may not “get there with you.” Here is that speech:

The obituaries

From the New York Times:

Martin Luther King Jr.: Leader of Millions in Nonviolent Drive for Racial Justice

“To many million of American Negroes, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was the prophet of their crusade for racial equality. He was their voice of anguish, their eloquence in humiliation, their battle cry for human dignity. He forged for them the weapons of nonviolence that withstood and blunted the ferocity of segregation.

“And to many millions of American whites, he was one of a group of Negroes who preserved the bridge of communication between races when racial warfare threatened the United States in the nineteen-sixties, as Negroes sought the full emancipation pledged to them a century before by Abraham Lincoln.

“To the world, Dr. King had the stature that accrued to a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, a man with access to the White House and the Vatican; a veritable hero in the African states that were just emerging from colonialism.” (Click here to continue reading)

Riots follow killing of Martin Luther King Jr.

“Before darkness fell on this day, a Friday, the plumes of smoke from the West Side already were visible to Loop office workers. In Chicago and across the nation, rioting was breaking out in response to the news that Martin Luther King Jr. had been gunned down in Memphis the day before.” (Click here to continue reading)

Robert Kennedy breaking the news

On April 4, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy was in Indianapolis, campaigning for the Democratic nomination for president when he was told of the assassination of King. His staff tried to dissuade Kennedy from going to speak to the crowd in a predominately Black neighborhood in the city, as news of riots were beginning to spread.

Kennedy insisted on going to the corner of 17th Avenue and Broadway and talking with the people gathered there. Kennedy began by breaking the news that King had been shot and killed, then called for calm and reminded those gathered that he, too, had had a family member killed and that his family member (his brother, John F. Kennedy) was killed by a white man.

Here is Kennedy’s speech that night:

President Lyndon Johnson’s response

Johnson was notified of King’s assassination as he readied for a trip to Hawaii. He postponed the trip, called King’s wife to offer condolences and declared April 7 a national day of mourning.

The front pages

To see how the world reacted to King’s assassination, click here.

From television:

Walter Cronkite on CBS

WSB radio tribute

King at the age of 6. (Handout)

‘Fentanyl intoxication’ was cause of death for boy who ate strawberries at fundraiser

- ‘Yellowstone’ spinoff actor Cole Brings Plenty death investigation indicates no foul play

O.J. Simpson, former NFL star acquitted of murder, dies at 76

- Recall alert: 500K bike stem raisers recalled

- Got a tattoo you hate? PetSmart contest gives you a shot at replacing it

© 2024 Cox Media Group

New Castle couple welcomes baby girl born on Pennsylvania Turnpike

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/cmg/ZUTUACGESVHHDGYJ5EATP4LHQI.jpg)

Airline offers service from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia for half the cost of traveling on PA Turnpike

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/cmg/W3ZEAFQN4FBXLOK5K6GASPYXBQ.jpg)

Pittsburgh police announce changes to the way they respond to burglar alarms

- Marketplace

- Marketplace Morning Report

- Marketplace Tech

- Make Me Smart

- This is Uncomfortable

- The Uncertain Hour

- How We Survive

- Financially Inclined

- Million Bazillion

- Marketplace Minute®

- Corner Office from Marketplace

- Latest Stories

- Collections

- Smart Speaker Skills

- Corrections

- Ethics Policy

- Submissions

- Individuals

- Corporate Sponsorship

- Foundations

How the family of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is working to protect his legacy

Share Now on:

- https://www.marketplace.org/2024/04/04/dr-martin-luther-king-jr-family-legacy/ COPY THE LINK

HTML EMBED:

Get the Podcast

- Amazon Music

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated 56 years ago today. His four children have worked to carry on his vision through his namesake center in Atlanta , which focuses on promoting nonviolent social change.

When a determined Dr. King gave his prophetic “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech to striking Memphis sanitation workers, it would be his last. In it, he urged his followers to keep marching, though conceding that he might not live to see the progress. His expectation was based on years of being violently attacked, having his house bombed and other assaults.

Dr. King was assassinated the very next day, on April 4, 1968, while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. King’s awareness of his mortality made him think about the future financial security of his family.

“ Our father was a public figure, but he was a private citizen,” said Bernice King, Dr. King’s youngest child and CEO of the King Center in Atlanta.

Fifty-six years since her father’s death, she and her siblings have fought to maintain access to her father’s words — especially her late brother, Dexter. She reflected on her brother’s work at a news conference following his death.

“Daddy protected his own intellectual property,” Bernice said. “He copyrighted and went to court over the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. And that we are following in his stead to adequately protect it so it doesn’t go off the rails, at least as long as we live and breathe in this first generation.”

Being King comes with the heavy responsibility of carrying the weight of her father’s name forward. “Many people would ask, ‘What is your legacy?’ said Bernice. “I tell them, ‘Look, I don’t have to discover a legacy — I was born into a legacy. We were born into a legacy. And we each have a defined role to carry forward that legacy.'”

The Martin Luther King, Jr. estate is worth nearly $10 million. However, there is no reliable way to account for the cost of the violence and trauma the family has endured.

Isaac Newton Farris, Jr., the son of Dr. King’s late sister, Christine King Farris, spoke about some of the painful moments that followed the civil rights leader’s assassination.

“The hardest death for any of us to deal with was the murder of my grandmother ,” Isaac Newton said. “She was the big mama in terms of our family. She was looked at by all of us as a loving, giving person.”

When asked if he was ever afraid as a child, Isaac Newton responded: “I was, because there were a couple of instances, a few times when literally the police came to my elementary school and just to say to the principal and to the teachers, ‘Look there, you know, there’s been a threat made against the family and not just Dr. King. You know, the threat is beyond them, and it is affecting the kids.'”

The family was often under FBI surveillance, especially in 1963, after King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech . Still, Isaac Newton doesn’t hold the government wholly responsible for the family’s trauma .

“We looked at it more as elements of the government; J. Edgar Hoover was an element of the government, but so was the Supreme Court. So was the Supreme Court that ruled in Brown vs. Board of Education. So was the American Congress and American Senate with no Black senators, and only five Black Congressmen that passed the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act,” he said.

For the King descendants, inheriting a brand that promotes nonviolent social change and racial unity has come with some pretty heavy burdens — but it has an inimitable place in the ongoing story of the United States.

Stories You Might Like

Remembering Martin Luther King Jr.’s fair housing legacy

Civil rights tourism sees more demand and destinations

Health and civil rights: an iconic family counts the costs

Low-wage workers are reviving Dr. King’s 1968 Poor People’s Campaign

The life and legacy of A.G. Gaston: a man who quietly helped fund the Civil Rights Movement

Last year’s successful strikes may prompt more labor actions in 2024

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on . For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.

Also Included in

- Civil rights

- Intellectual property

- Social change

Latest Episodes From Our Shows

Why are media mergers so tough to pull off?

$6.6 billion TSMC deal in Arizona the latest in the CHIPS Act's rollout

How landlords and tenants are reacting to a changing rental market

In Indian Country, federal budget dysfunction takes a toll

King family, National Civil Rights Museum commemorate Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. assassination anniversary: Here are 5 landmarks that reveal civil rights struggle

Martin Luther King Jr. was shot dead 56 years ago today in Memphis, Tennessee .

His assassin "hoped to kill MLK's great and widespread dream of unity," Alveda King, the civil rights leader's niece, posted on Thursday morning, April 4, on social media.

The killer failed in his mission, King wrote in her message.

CHRISTIAN FILMMAKER JIM WAHLBERG SAYS MOTHER TERESA ‘LED ME’ TO GOD AND TO SOBRIETY IN PRISON

"Praise God … The dream didn't die with my uncle. His dream is alive, and so are our dreams; for our Lord Jesus is alive," she wrote.

The night before he was murdered, the powerful orator thundered prophetically from the pulpit of Bishop Charles Mason Temple in Memphis, "Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord."

READ ON THE FOX NEWS APP

King Jr.'s death was only the first of several tragedies suffered by the family. Rev. A.D. King, Martin's little brother – Alveda King's father – died under mysterious circumstances the following year.

Her grandmother, Alberta King, also died shockingly. She was shot dead in 1974 in front of a Sunday congregation at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia from where the King family led the civil rights movement.

King Jr.'s life on Earth ended in Memphis. But the civil rights movement he led marched across a vast swath of the country.

Alveda King, when asked by Fox News Digital, suggested visiting these five landmarks in the civil rights movement to learn more about the march for justice – and the price paid by her family.

Rev. A.D. King, just 18 months younger than his brother Martin Jr., was ministering at the First Baptist Church of Ensley and leading the Birmingham Campaign of the civil rights movement in the tumultuous year of 1963.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO GAVE BIRTH TO THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, ALBERTA KING, ‘GAVE HER ALL FOR CHRIST’

Two bombs exploded at the reverend's home in an assassination attempt on May 11, while he was home with his wife, Naomi, and five children – including Alveda King, who was just 12 years old at the time.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. and his wife Alberta (Williams) King lived in a beautiful Queen Anne-style home at 501 Auburn Ave. when they welcomed three children: daughter Willie Christine and her younger brothers, Martin Jr. and Alfred Daniel (A.D.).

The home today is a centerpiece of the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park.

The home is closed for an "extensive rehabilitation project" through Nov. 2025 following an attempted arson attack in December 2023.

The exterior remains a coveted bucket-list destination for photographs and selfies.

The congregation was founded in 1886 with just 13 members. Rev. Adam Daniel Williams, MLK's Jr. grandfather, became minister in 1894.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO WROTE ‘THE BATTLE HYMN OF THE REPUBLIC’

The church blossomed and became the spiritual headquarters of the civil rights movement under the Williams-King family by the 1950s.

The church also grew famous for its choir and music , led by Alberta King, Martin Jr.'s mother. The choir performed at the Atlanta premier of the movie "Gone with the Wind" in 1939.

Martin Luther King Jr. was both baptized at and mourned from Ebenezer Baptist on April 9, 1968. The funerals for both his brother and mother were held at the church, as well.

The bridge over the Alabama River became the center of global attention on March 7, 1965, as civil rights demonstrators, marching to Birmingham in favor of voting rights, met a violent response on "Bloody Sunday."

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

"The televised attacks were seen all over the nation, prompting public support for the civil rights activists in Selma and for the voting rights campaign," writes CivilRightsTrail.com.

The Edmund Pettus Bridget today is a National Historic Landmark and the frequent site of events and commemorations in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. and the battle for civil rights.

Now the Bayfront Motel, the Monson Motor Lodge was the scene of one of the most unusual and disturbing events in the march for civil rights.

Alveda King cited it as a nearly forgotten event that speaks to the dangers faced by civil rights activists.

A bi-racial group of people plunged into the motor-lodge swimming pool on June 18, 1964, to protest segregation.

James Brock, the manager of the inn, responded by pouring acid into the pool – a potentially disfiguring and even deadly attack.

Photos of the shocking incident hit newspapers nationally.

"The searing image helped propel passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing discrimination in public places," First Coast News of Florida wrote last year.

For more Lifestyle articles, visit www.foxnews.com/lifestyle .

Original article source: Martin Luther King Jr. assassination anniversary: Here are 5 landmarks that reveal civil rights struggle

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Martin Luther King Jr’s family to visit Memphis on anniversary of his murder

The relatives of slain civil rights leader will visit Tennessee city to bring attention to erosion of civil rights in US

Relatives of the late civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr are making a rare trip to Memphis on Thursday on the anniversary of his assassination, to speak on the rising threat of political violence, especially in an election year.

Martin Luther King III, the eldest son of the late King, will pay tribute to his father’s legacy, 56 years after the assassination in the Tennessee city.

King was shot and killed in 1968 as he stood on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel in downtown Memphis.

On Thursday, King III will host a public celebration of of his father’s life and activism at the historic National Civil Rights Museum, which is located near the Lorraine motel, the Memphis Commercial Appeal reported .

The event will end with a moment of silence, marking the time when King was killed.

Relatives of King do not generally make the pilgrimage to Memphis, and certainly not as a family unit, but have said they felt it was necessary to do so during a presidential election year in which the US is so divided and violent rhetoric is becoming routine, chiefly from the far right.

“This is the first year that we actually are going back as a family to Memphis, and we felt that it was extraordinarily important to be there in that spot this year,” King III’s wife, Arndrea Waters King, said to Axios .

King III told Axios that his family was growing concerned at the lack of civility in politics.

“We believe we have to go into difficult areas, to use our platform, to use our voice to lift up what we believe is good, just and right. And so we’re willing to make a sacrifice,” King III said, adding that the family was determined to visit Memphis in spite of its painful associations.

Arndrea Waters King added that the latest commemoration of King’s legacy and untimely death comes as civil rights in the US are eroding .

“We feel that in some ways there’s a backward movement from the dream,” she said to Memphis Magazine .

after newsletter promotion

“Laws are being passed where our daughter – Dr King’s only grandchild – has fewer rights now at 16 than the day that she was born,” she added, referring to her daughter, 15-year-old Yolanda Renee King.

In recent years, the supreme court has rolled back federal abortion protections and affirmative action , which promoted greater student diversity at US colleges and universities.

King III has also spoken out against attacks on voting rights, especially as the US Senate failed to pass meaningful voting rights legislation in 2022 and the supreme court further eroded protections.

“We’re gonna continue to push to get something done. Because to me, it’s fundamental to the foundation of our democracy. It’s those on the other side who seem to have lost the perception of what democracy is,” King III said of voting rights in a 2022 interview.

- Martin Luther King

- Civil rights movement

- Women's health

- Reproductive rights

Most viewed

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Full text to the "I Have A Dream" speech by Dr. Martin Luther King Junior I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation. Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

The "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered by Martin Luther King, Jr. before a crowd of some 250,000 people at the 1963 March on Washington, remains one of the most famous speeches in history.

Martin Luther King's I Have A Dream speech text and audio . Martin Luther King, Jr. I Have a Dream. delivered 28 August 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington D.C. ... (IPM), the exclusive licensor of the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. at [email protected] or 404 526-8968. Image #1 = Public domain ()per data here). Image #2 ...

August 28, 1963. Martin Luther King's famous "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered at the 28 August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, synthesized portions of his previous sermons and speeches, with selected statements by other prominent public figures. King had been drawing on material he used in the "I Have a Dream" speech ...

Martin Luther King, Jr. A. Philip Randolph. I Have a Dream, speech by Martin Luther King, Jr., that was delivered on August 28, 1963, during the March on Washington. A call for equality and freedom, it became one of the defining moments of the civil rights movement and one of the most iconic speeches in American history. March on Washington.

I Have a Dream, August 28, 1963, Educational Radio Network [1] " I Have a Dream " is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister [2] Martin Luther King Jr. during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, King called for civil and economic rights and an end to ...

The Institute cannot give permission to use or reproduce any of the writings, statements, or images of Martin Luther King, Jr. Please contact Intellectual Properties Management (IPM), the exclusive licensor of the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. at [email protected] or 404 526-8968. Screenshots are considered by the King Estate a ...

"I Have a Dream" Speech by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at the "March on Washington," 1963 (excerpts ) I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation. Five score years ago a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand today signed the

Freedom's Ring is Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, animated. Here you can compare the written and spoken speech, explore multimedia images, listen to movement activists, and uncover historical context. Fifty years ago, as the culminating address of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, King demanded the riches ...