New Research

What Does Science Say About the Five-Second Rule? It’s Complicated

The real world is a lot more nuanced than this simple rule reflects

Aaron Sidder

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/8c/9a8cdbc4-9578-4060-89f3-302edc391f76/istock_35668758_medium.jpg)

Many people of all ages agree: Food, when dropped on the floor, remains “good” for five seconds. But this pillar of American folklore, the so-called “five-second rule,” is now under attack from scientists at Rutgers University .

Though the five-second rule may seem like a silly line of inquiry, food safety is a major health burden in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that every year, one in six Americans (roughly 48 million people) get sick from foodborne illness, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die.

“We decided to look into this because the [five-second rule] is so widespread. The topic might appear ‘light,’ but we wanted our results backed by solid science,” Donald Schaffner , food scientist at the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences , told Rutgers Today .

Schaffner and his graduate student Robyn Miranda tested different bacteria transfer scenarios using four surfaces (stainless steel, ceramic tile, wood, and carpet) and four foods (watermelon, bread, bread and butter, and gummy candy).

They inoculated each surface with Enterobacter aerogenes —a nonpathogenic “cousin” of Salmonella bacteria that occurs naturally in the human digestive system—and dropped the food on each surface for differing lengths of time (less than one second, five, 30, and 300 seconds). The food samples were then analyzed for contamination. In total, the different combinations of surface, food, and length of contact yielded 128 scenarios, each of which was replicated 20 times. The pair published their results in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology .

The duo didn’t necessarily disprove the five-second rule, showing that bacteria transfer does increase with contact time. However, their findings reveal a more nuanced reality than that imparted in common playground wisdom.

“The five-second rule is a significant oversimplification of what actually happens when bacteria transfer from a surface to food,“ Schaffner said. “Bacteria can contaminate instantaneously.”

By food, watermelon collected the most bacteria, and gummy candy the least. According to Schaffner, moisture drives the transfer of bacteria from surface to food; the wetter the food, the higher the risk of transfer.

Looking at the surfaces, tile and stainless steel had the highest rates of contamination transfer. Somewhat surprisingly, carpet had the lowest rate of transfer, and the rate was variable on the wood surface. In the end, they found that many factors contribute to contamination: The length of contact, the characteristics of the surface and the moisture of the food all play a role.

Schaffner and Miranda are the not the first to investigate the five-second rule, but peer-reviewed research is limited. In 2013, the popular MythBusters duo also found that moist foods collected more bacteria than drier foods, and an undergraduate research project tested the rule in an unpublished 2003 study from the University of Illinois. Interestingly, the Illinois study found that women are both more familiar with the rule than men and more likely to eat food off the floor.

Unsurprisingly, the Illinois researchers also found that cookies and candy were more likely to be picked up and eaten than cauliflower and broccoli, which raises an important question. If we really want that food, does it matter how long it has been on the floor?

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Aaron Sidder | | READ MORE

Aaron Sidder is an ecologist and a freelance science writer based in Denver, CO. He is a former AAAS Mass Media Fellow whose work has appeared National Geographic and Eos.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- FEMS Microbiol Lett

Can I still eat it? Using problem-based learning to test the 5-second rule and promote scientific literacy

Elizabeth a hussa.

1701 N. State Street, Jackson, MS 39210. Millsaps College

Associated Data

Defining appropriate student learning outcomes for general education science courses is a daunting task. We must ask ourselves how to best prepare our students to understand the role of science in their lives and in society at large. In the era of social media and armchair experts, life-changing scientific advancements such as vaccination are being dismissed or actively resisted, emphasizing the critical need to teach science literacy skills. One active classroom method known as problem-based learning promotes self-motivated learning and synthesis skills that, when applied in a science-literacy context, can provide students with the ability to generate informed opinions on new scientific advances throughout their lifetime. This piece describes one such problem-based course, designed to tackle the scientific basis (or lack thereof) of the 5-second rule for eating food dropped on the floor. In this course, first year students experimentally engage this issue, while also applying their developing skill set to sort out scientific controversies such as vaccine safety and genetically modified foods.

This work provides both a theoretical and actionable blueprint for the development of a problem-based microbiology course for non-major undergraduate students to promote science literacy.

PROBLEM-BASED LEARNING

In problem-based learning (PBL) pedagogy, student groups engage with an open-ended question or related set of questions as a means to encounter course content while developing discipline-specific problem-solving tools (Barrows and Tamblyn 1980 ). Originally developed as a means to connect information to application in medical education, this method is one of the ways we can teach science as science is done. In fact, simply engaging students in hypothesis-driven research is a PBL methodology. The goals of PBL include the development of self-directed and motivated learning skills, usually with an emphasis on collaboration (Barrows and Kelson 1995 ). This shift toward skill development puts PBL well in line with a modern approach to science education (AAAS 2011 ), however there is lingering concern about the potential sacrifice of course content, which can lead to reduced scoring on standardized tests (Hmelo-Silver 2004 ). Current trends in undergraduate biology education resolve these concerns by placing PBL classes, including undergraduate research projects, near the beginning of the curriculum in an effort to ‘jump start’ student engagement and with the hope that students will develop the metacognitive skills necessary to succeed in their approach to content-driven courses that they encounter later in the curriculum (Russell, Hancock and McCullough 2007 ).

While PBL is quickly becoming an important part of a science curriculum, it could also be an important approach to teaching non-majors science courses. These general education courses are often our one opportunity to reach students who will go out into the world and be faced with making tough decisions about scientific progress from the doctor's office to the voting booth. This would support the call to emphasize science literacy skills, or the ability to acquire, critically evaluate, and apply scientific knowledge to new problems in these general education courses (Wright 2005 ). While the occasional ‘traditional’ general biology student may think about aerobic versus anaerobic respiration while gasping for air and racing to get their child to the pediatrician's office on time, one might argue that it is more impactful that they can make an informed decision as to the safety of vaccinating their child once they get there. PBL courses can help these students develop the ability to critically evaluate sources, understand data and recognize the importance of statistics when researching these important issues.

As microbiologists, we are in a unique position to offer problem-based courses to students at all levels, regardless of major because classic microbiological methods and questions are (1) accessible, (2) relevant to everyday life and (3) inexpensive. As instructors, we can invest a small amount of time training students how to inoculate petri plates and use proper sterile technique, preparing them for an entire semester of inquiry. We can subsequently spend more of our contact hours with students focused on hypothesis development and testing, as well as data analysis. Innovative microbiology-based pedagogies are becoming more popular (Strobel and Strobel 2007 ; Jordan 2014 ; Fahnert 2017 ), and are making their way into general education curricula as a means to reach a diverse population of students. Bard College has a mandatory, microbiology-based ‘Citizen Science’ course that challenges first year students to engage with primary literature and perform wet lab experimentation centered around a current scientific issue (Savage and Jude 2014 ). At Millsaps College, I have offered a similar first year course titled ‘The 5-second Rule: Can I Still Eat it?’ since the fall of 2015. The course directs students to experimentally examine the popular folklore about the safety of eating dropped food retrieved before 5 seconds, while at the same time asking them to link what they’ve learned to ‘bigger picture’ scientific controversies. The course is taught in three phases, which are outlined below.

Phase I: Setting the stage

Teaching a PBL course can feel very foreign to those of us used to traditional lecture-based teaching methods. The instructor in a PBL course must put the majority of their effort into the setup of the course in order to facilitate student-driven learning during course execution. This typically involves providing a framework to which problem solving can be applied (Schmidt et al. 2007 ). In science, of course, this framework is the scientific method. In the 5-second rule, we spend the first 2-3 weeks setting the stage, wherein student groups engage with hypothetical scenarios to facilitate discussion of the scientific method. For example, students are asked to develop an experiment to test the hypothesis that college students like both oatmeal and chocolate chip cookies, but prefer chocolate chip. This results in a discussion of the elements of good experimental design so that we can layer on, or ‘scaffold’ scientific knowledge and techniques later. Another scenario presents students with two data sets representing differences in student height by sex. Each data set has the exact same sample size and average height, but different distributions of data. This prompts discussion of data analysis, including basic statistics (Student's t- test). These exercises provide a low stakes way for students to build confidence toward eventual application of the scientific method.

Phase II: Experimental investigation

The second phase of the 5-second rule allows students to apply their knowledge of the scientific method to experimentation by first dividing the 5-second rule into single-variable experimental questions. Typically, students will choose to investigate (1) the presence of microbes on various surfaces onto which food might be dropped, (2) the effect of food type on microbial transfer and (3) the effect of time of surface exposure on microbial transfer. For each experiment, the student group will first find relevant information from reliable sources to develop a hypothesis. Next, they will be given a list of materials they will be able to access for their experiment. This provides more scaffolding for students to feel supported and give them subtle direction without handing them a protocol. Groups then develop experimental methods using a handout that asks them to identify controls and predict results based on their hypothesis. After meeting with the instructor and receiving approval to move forward, student groups conduct experiments independently and meet with an instructor or teaching assistant to ensure proper data interpretation. An example set of assignments for a single experiment is included in the supplementary materials . Finally, the group prepares a standard laboratory report with a collaboratively-written abstract and individually-written introduction, methods, results and conclusion sections. Students rotate written sections throughout the semester so they can isolate and focus on one section at a time. Finally, students within a group engage in peer review of their collective work prior to submission. The last experiment of the semester involves conducting a multi-variable experiment to test the 5-second rule, with individually-written lab reports.

Phase III: Metacognition and application

One of the goals of PBL courses in general is to provide students with lifelong learning skills, as well as the ability to understand and apply these skills in other courses, or even in everyday life. Otherwise known as metacognition, the ability to ‘think about thinking’ is useful, especially in a student's early college career, to develop productive study habits (Downing et al. 2009 ). With this in mind, the third component of the 5-second rule course is actually distributed throughout the semester as a series of ‘hot topics in science’ discussions. Here, students investigate and discuss various controversies using a scientific basis for understanding. For example, one exercise may have students use a standard internet search engine to investigate the relative safety of genetically modified organisms. Students are instructed to categorize the search results as reliable or unreliable based on their knowledge of appropriate sources for science communication, and the class subsequently compares the relative abundance of reliable versus unreliable sources on the internet. It is critical that students participate in and reflect on a variety of problems so as to emphasize the universal nature of problem solving practices.

Engaging with both scientific experimentation and literature via problem-based learning provides a depth of experience that benefits students as lifelong learners. After course completion, 90% of 5-second rule students indicated that ‘taking this class has made me more likely to understand an article describing a scientific discovery’ ( P < 0.0001). The relatability and experimental tractability of microbiological problems such as the 5-second rule places our field at the forefront of these important pedagogical innovations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data.

This work was supported by the Mississippi IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Ethics (INBRE), funded by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [grant number P20GM103476].

Conflict of interest . None declared.

- AAAS Vision and Change in Undergraduate Biology Education: A Call to Action . Washington, DC: AAAS, 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrows HS, Tamblyn RM. Problem-Based Learning: An Approach to Medical Education . New York: Springer Pub. Co., 1980. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrows HS, Kelson A. Problem-based learning and secondary education and the problem-based learning institute . (Medicine SIUSo, ed.) p.pp. Springfield, IL: Problem-Based Learning Institute, 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Downing K, Kwong T, Chan SW et al.. Problem-based learning and the development of metacognition . High Educ 2009; 57 :609–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fahnert B. Keeping education fresh-not just in microbiology . FEMS Microbiol Lett 2017; 364 , DOI: 10.1093/femsle/fnx209. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hmelo-Silver CE. Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educ Psychol Rev 2004; 16 :235–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jordan TC, Burnett SH, Carson S et al.. A broadly implementable research course in phage discovery and genomics for first-year undergraduate students . mBio 2014; 5 :e01051–01013. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell SH, Hancock MP, McCullough J. The pipeline. Benefits of undergraduate research experiences . Science 2007; 316 :548–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Savage AF, Jude BA. Starting small: Using microbiology to foster scientific literacy . Trends Microbiol 2014; 22 :365–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schmidt HG, Loyens SMM, van Gog T et al.. Problem-based learning is compatible with human cognitive architecture: Commentary on Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006) . Educ Psychol 2007; 42 :91–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- Strobel SA, Strobel GA. Plant endophytes as a platform for discovery-based undergraduate science education . Nat Chem Biol 2007; 3 :356–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wright RL. Points of View: Content versus Process: Is This a Fair Choice? . CBE 2005; 4 :189–96. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

The science is in, and deciding whether to eat that chip is not as simple as snatching it up within five seconds.

- GORY DETAILS

The Truth Behind the Five-Second Rule Revealed

Step away from the cookie.

Throughout our lives, we are dogged by a question that challenges our perceptions of time and space: Is it safe to eat food you’ve dropped if you pick it up quickly enough?

The good old five-second rule. It’s been the subject of household debates and innumerable science fair projects, with some claiming it’s real and others denouncing it as bunk. And now this famous rule of thumb is in the headlines again, with a new study putting it to a yet more rigorous test.

Why hasn’t science solved what seems like a simple question—or has it?

The new experiments , reported in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology , show that the five-second rule is really no rule at all. True, the longer food sat on a bacteria-coated surface, the more bacteria glommed onto it—but plenty of bacteria was picked up as soon as the tasty edibles hit the ground.

The bigger culprit here is not time but moisture. Wet food (watermelon in this case) picked up more bacteria than drier food, like bread or gummy candy. Carpeted surfaces transferred fewer bacteria to food than did tile or stainless steel, since it soaked up the bacterial solution the scientists applied. (But no, the scientists say, that doesn’t mean you should trade in your dishware for throw rugs.)

All of that is pretty intuitive, so why did we need a fancy experiment with more than 2,500 measurements of bacterial transfer rates?

Well, for starters, a lot of other folks are getting it wrong, says food scientist Donald Shaffner of Rutgers University, who conducted the study with his student Robyn Miranda. Amateur scientific studies and televised “investigations” have confused the issue by relying on experiments that don’t pass scientific muster.

In fact, to date there has been only one other rigorous inquiry into the five-second rule: a peer-reviewed study by Paul Dawson, a food scientist at Clemson University, in 2007. Dawson and colleagues likewise reported that food can pick up bacteria immediately on contact with a surface—but that study focused more on how long bacteria could survive on surfaces to contaminate food. Shaffner’s team decided to test a more robust variety of food under more diverse conditions.

So, if science has debunked the five-second rule, does that mean it’s unsafe to eat food that has hit the floor? That depends on the surface and what kind of bacteria you might pick up. “If you’re in a hospital and you drop something, you probably don’t want to eat it,” Dawson says. Likewise, you certainly wouldn’t want to pick up Salmonella from a kitchen floor covered in chicken juice.

But in most cases, eating a cookie that has picked up a little dust and floor bacteria is not likely to harm someone with a healthy immune system. “Ninety-nine percent of the time, it’s probably safe,” he says. Practicing good sanitation by keeping floors and surfaces clean is the most important lesson in all of this.

Still, the five-second rule will likely endure. “People really want this to be true,” Shaffner says. “Everybody does this; we all eat food off the floor.”

Perhaps the value of the five-second rule (or the three-second rule, if you’re more uptight) lies more in psychology than microbiology. If nothing else, having a rule provides a socially acceptable excuse for our unsavory behavior. Just holler "Five-second rule!" before picking a cookie off the floor and popping it into your mouth, and everyone can have a good laugh. It’s a bit like calling shotgun before elbowing your way into the front passenger seat.

And that leaves us with another way to decide whether to eat that jelly bean you dropped: Just see if anyone’s looking.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

You May Also Like

What to do when you see mold on your food

The holidays can take a toll on your gut health. Here’s how to deal.

Salmonella can be deadly. Here’s how to protect yourself from it.

Why is stomach cancer rising in young women?

There’s another biome tucked inside your microbiome—here’s why it’s so important

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

- History & Culture

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

March 25, 2014

Fact or Fiction?: The 5-Second Rule for Dropped Food

There may be some actual science behind this popular deadline for retrieving grounded goodies

By Larry Greenemeier

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

You’re about to savor your first bite from a delicious candy apple when, just as your teeth are about to sink in, the fruit–candy combo slips from its stick and plummets to the ground. The clock is ticking. You quickly snatch the fallen morsel, well within five seconds—the acknowledged time limit for determining whether dropped food should end up in your mouth or in the trash. What happens next is generally a judgment call depending on several factors—what was dropped, where it was dropped and the victim’s level of hunger. What to do could also pivot on whether or not the most recent health column you read covering this topic on the Web said that you could get away with putting the dropped food in your mouth without a trip to the emergency room. A lot of research—and common sense, really—might indicate that any dropped food carries a risk of collecting bacteria. So the only real questions might be how great the risk is and whether it’s worth taking. Food retrieved just a few seconds after being dropped is less likely to contain bacteria than if it is left for longer periods of time, researchers at Aston University’s School of Life and Health Sciences in England recently reported . The Aston team also noted that the type of surface on which the food has been dropped has an effect, with bacteria least likely to transfer from carpeted surfaces. Bacteria is much more likely to linger if moist foods make contact for more than five seconds with wood laminate or tiled surfaces. The current study, undertaken by six final-year biology students led by Aston microbiology professor Anthony Hilton , is likely to only inflame an ongoing debate about this informal rule of food safety, as other studies have found that pathogens transfer themselves to food as soon as that piece of meat or candy hits the kitchen tiles. The researchers found that the initial impact immediately transferred at least a small proportion of bacteria resident on a floor to just about any type of food. Moist foods left longer than 30 seconds, however, contained up to 10 times more bacteria than food picked up after three seconds. “We believe that additional contact is being made between the moist food and the floor as it settles further onto the floor,” Hilton says. Dry foods dropped on the carpet experienced the slowest rate of bacterial migration. The researchers monitored the transfer of the common bacteria Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus — the latter of which causes staph infections — from a variety of indoor floor types to toast, pasta, biscuits and a sticky sweet when contact was made from three to 30 seconds. Hilton and his students had initially been studying the survival and transfer of bacteria on indoor flooring surfaces. The researchers found staph to be the most commonly isolated bacterium on the flooring they examined. They included E. coli in their work because it is a common gut bacterium, often used to model how other gut pathogens—such as salmonella —respond under different conditions. “We introduced time as a factor as a bit of a quirky parameter to explore and didn’t really expect it to show anything significant,” he says. The researchers speculate that the contact area made between food and floor surface is significant. “On a smooth surface like tile or laminate the area of contact is greater than when the food is suspended on the tips of the fibers of the carpet,” Hilton says. “I think the results from the carpet were the most surprising in transferring very low numbers of bacteria to food and not demonstrating the same effect of time in enhancing transfer.” Most of the 495 people that Hilton and his team surveyed as part of their research had heard of the so-called “five-second rule” but “there was still a good number of people that hadn’t,” he says. Regardless, 87 percent of survey participants who adhere to the five-second rule said they would eat food dropped on the floor or already have done so. The researchers also found that 81 percent of females surveyed use the rule, compared with 64 percent of males. Hilton says he doesn’t have a good explanation for this gender differentiation but points out that this finding is consistent with other research into the five-second rule. One possible conclusion: This is tacit confirmation of another piece of folk wisdom—men are less discerning when it comes to their food’s cleanliness. The research began as a class project, but Hilton says widespread interest in the results has encouraged him to prepare the work for submission to a peer-reviewed journal. The Aston findings give the dropped-food guideline more legitimacy than have other studies, which tend to consider the rule unadulterated baloney. “We found that bacteria was transferred from tabletops and floors to the food within five seconds—that is, the five-second rule is not an accurate guide when it comes to eating food that has fallen on the floor,” said Paul Dawson , a professor in Clemson University’s Department of Food, Nutrition and Packaging Sciences, following his 2007 study. That study, published in the Journal of Applied Microbiology , was primarily aimed at measuring the persistence of bacteria on surfaces. The Clemson researchers found that Salmonella typhimurium “can be transferred to the foods tested almost immediately on contact” and that the bacteria can survive for up to four weeks on dry surfaces in high-enough populations to be transferred to foods. A 2003 study by then high-school senior Jillian Clarke , during an internship at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, likewise found that bacteria transfers to food immediately on contact. In her experiment E. coli moved from floor tiles to cookies and gummy bears well within five seconds. Most studies, it would seem, discourage adherence to the five-second rule. So, even though Aston’s findings suggest that allowing dropped food to linger on the floor certainly increases the risk of bacterial transfer to that fallen indulgence, it’s better to think twice before eating anything that touches an unsavory surface—whether it’s your kitchen floor or your favorite diner.

Does The 5-Second Rule Hold Up Scientifically?

Short answer: it depends on what bacteria are on the floor

By Paul Dawson/The Conversation | Published Sep 15, 2015 7:44 PM EDT

When you drop a piece of food on the floor, is it really okay to eat if you pick up within five seconds? This urban food myth contends that if food spends just a few seconds on the floor, dirt and germs won’t have much of a chance to contaminate it. Research in my lab has focused on how food and food contact surfaces become contaminated, and we’ve done some work on this particular piece of wisdom.

While the “five-second rule” might not seem like the most pressing issue for food scientists to get to the bottom of, it’s still worth investigating food myths like this one because they shape our beliefs about when food is safe to eat.

So is five seconds on the floor the critical threshold that separates an edible morsel from a case of food poisoning? It’s a bit a more complicated than that. It depends on just how much bacteria can make it from floor to food in a few seconds and just how dirty the floor is.

Where did the five-second rule come from?

Wondering if food is still OK to eat after it’s been dropped on the floor (or anywhere else) is a pretty common experience. And it’s probably not a new one either.

A well-known, but inaccurate, story about Julia Child may have contributed to this food myth. Some viewers of her cooking show, “The French Chef,” insist they saw Child drop lamb (or a chicken or a turkey, depending on the version of the tale) on the floor and pick it up, with the advice that if they were alone in the kitchen, their guests would never know.

In fact it was a potato pancake, and it fell on the stovetop, not on the floor. Child put it back in the pan, saying “But you can always pick it up and if you are alone in the kitchen, who is going to see?” But the misremembered story persists .

It’s harder to pin down the origins of the oft-quoted five-second rule, but a 2003 study reported that 70 percent of women and 56 percent of men surveyed were familiar with the five-second rule and that women were more likely than men to eat food that had been dropped on the floor.

So what does science tell us about what a few moments on the floor means for the safety of your food?

Five seconds is all it takes

The earliest research report on the five-second rule is attributed to Jillian Clarke , a high school student participating in a research apprenticeship at the University of Illinois. Clarke and her colleagues inoculated floor tiles with bacteria then placed food on the tiles for varying times.

They reported bacteria were transferred from the tile to gummy bears and cookies within five seconds, but didn’t report the specific amount of bacteria that made it from the tile to the food.

But how much bacteria actually transfer in five seconds?

In 2007, my lab at Clemson University published a study – the only peer-reviewed journal paper on this topic – in the Journal of Applied Microbiology . We wanted to know if the length of time food is in contact with a contaminated surface affected the rate of transfer of bacteria to the food.

To find out, we inoculated squares of tile, carpet or wood with Salmonella. Five minutes after that, we placed either bologna or bread on the surface for five, 30 or 60 seconds, and then measured the amount of bacteria transferred to the food. We repeated this exact protocol after the bacteria had been on the surface for two, four, eight and 24 hours.

We found that the amount of bacteria transferred to either kind of food didn’t depend much on how long the food was in contact with the contaminated surface – whether for a few seconds or for a whole minute. The overall amount of bacteria on the surface mattered more, and this decreased over time after the initial inoculation. It looks like what’s at issue is less how long your food languishes on the floor and much more how infested with bacteria that patch of floor happens to be.

We also found that the kind of surface made a difference as well. Carpets, for instance, seem to be slightly better places to drop your food than wood or tile. When carpet was inoculated with Salmonella, less than 1 percent of the bacteria were transferred. But when the food was in contact with tile or wood, 48%-70 percent of bacteria transferred.

Last year, a study from from Aston University in the UK used nearly identical parameters to our study and found similar results testing contact times of three and 30 seconds on similar surfaces. They also reported that 87 percent of people asked either would eat or have eaten food dropped on the floor.

Should you eat food that’s fallen on the floor?

From a food safety standpoint, if you have millions or more cells on a surface, 0.1 percent is still enough to make you sick. Also, certain types of bacteria are extremely virulent, and it takes only a small amount to make you sick. For example, 10 cells or less of an especially virulent strain of E. coli can cause severe illness and death in people with compromised immune systems. But the chance of these bacteria being on most surfaces is very low.

And it’s not just dropping food on the floor that can lead to bacterial contamination. Bacteria are carried by various “media,” which can include raw food, moist surfaces where bacteria has been left, our hands or skin and from coughing or sneezing.

Hands, foods and utensils can carry individual bacterial cells, colonies of cells or cells living in communities contained within a protective film that provide protection. These microscopic layers of deposits containing bacteria are known as biofilms and they are found on most surfaces and objects.

Biofilm communities can harbor bacteria longer and are very difficult to clean. Bacteria in these communities also have an enhanced resistance to sanitizers and antibiotics compared to bacteria living on their own.

So the next time you consider eating dropped food, the odds are in your favor that you can eat that morsel and not get sick. But in the rare chance that there is a microorganism that can make you sick on the exact spot where the food dropped, you can be fairly sure the bug is on the food you are about to put in your mouth.

Research (and common sense) tell us that the best thing to do is to keep your hands, utensils and other surfaces clean.

This article was originally published on The Conversation . Read the original article .

Like science, tech, and DIY projects?

Sign up to receive Popular Science's emails and get the highlights.

It’s a wonderful world — and universe — out there.

Come explore with us!

Science News Explores

The five-second rule: myth busted.

After the bologna drops and the microbes grow, it’s time to look at the unappetizing results

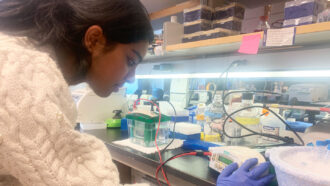

Is this bologna bacteria-free? An experiment should answer that question. Now it’s time to analyze the data.

Share this:

- Google Classroom

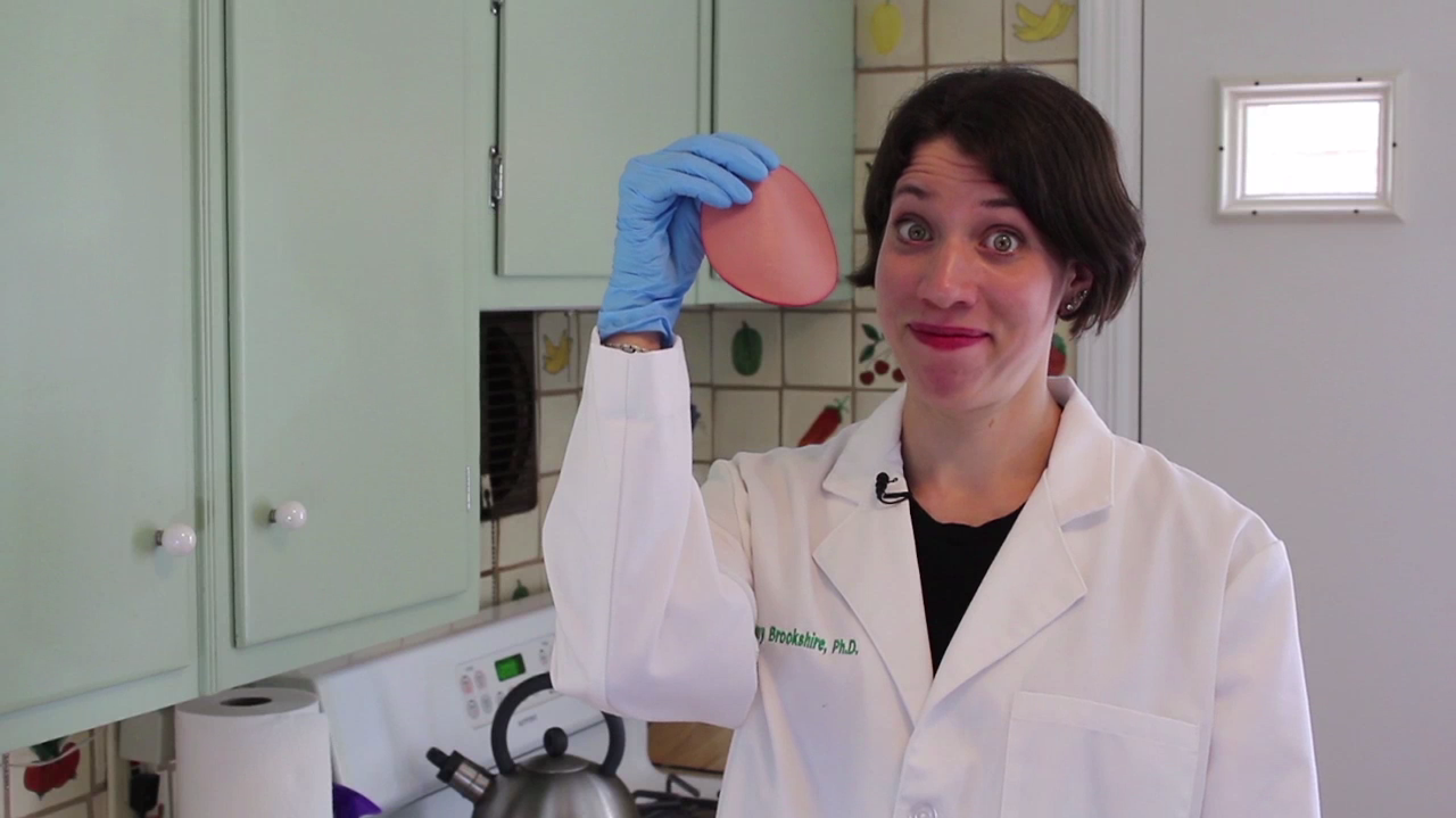

By Bethany Brookshire

September 13, 2017 at 9:16 am

This article is one of a series of Experiments meant to teach students about how science is done, from generating a hypothesis to designing an experiment to analyzing the results with statistics. You can repeat the steps here and compare your results — or use this as inspiration to design your own experiment.

View the video

Many of us have dropped food on the floor — then picked it up and eaten it. Some people even say that if the food has been on the floor for less than five seconds, it’s probably still clean. But does time even matter? The latest DIY Science video tests whether that “five-second rule” is true. The results show that bacteria are everywhere, and they are not waiting before hopping onto your food.

In fact, our bologna grew plenty of bacteria, even if it wasn’t dropped at all. Five seconds, 50 seconds or zero seconds made no difference.

In the first blog post , we came up with a hypothesis to test: that food picked up off the floor after five seconds will collect fewer bacteria than food left on the floor for 50 seconds. To test this hypothesis, we dropped bologna. Then we figured out how to measure how dirty or clean the bologna was by growing bacteria in petri dishes. We needed six groups of dishes. (One was a control. One grew microbes from bologna that had never been dropped. The other four hosted bacteria swabbed from bologna that sat for five or 50 seconds each on sections of clean and dirty floor.)

Our second blog post described how I performed the experiment, from dropping the bologna to growing any microbes that were on the food. After each drop, I swabbed the meat carefully and rubbed the swab on a petri dish containing agar — a gel-like substance bacteria like to munch on. The plates then sat for three days in a homemade incubator, which kept them warm.

Counting colonies

On each of those three days, I photographed each plate with a smartphone. I made sure the light was the same for all my images, and I took my pictures at the same time every day. I uploaded the pictures to a computer and used a program — ImageJ — to count how many colonies of microbes grew. ImageJ is available to download free from the National Institutes of Health. It’s used to analyze science images. Details on how to use the program to count colonies can be found in this tutorial .

Since I had 36 plates and photographed each of them three times, I had to run the ImageJ analysis 108 times! After each run, I noted the number of colonies. (I used a computer spreadsheet, Microsoft Excel, but other programs, such as Google Sheets, will also work. My full data tables are at the bottom of this post.)

Then, for each group and each day, I calculated the mean — or average — number of microbial colonies. To find that number, I added the colonies from all six petri dishes from a single test condition and divided the result by six (which is the number of plates per group). I also calculated the standard error of the mean . That’s how much the numbers of colonies might vary in general, based on the plates sampled. (For more on how to calculate this number, read this blog post .)

Once I had calculated all the means and standard errors, I graphed the results using a free trial of the program GraphPad Prism .

In the chart, each grouping of three bars represents the colonies counted on the dishes over three days. The groupings are labeled along the bottom, on the x axis . The vertical, or y axis , marks the number of microbial colonies that grew on the plates. The bars on far left represent the control; it had no bologna, just agar and distilled water. To its right is bologna that was never dropped. The two middle groups are bologna dropped on a clean floor and left for five and 50 seconds. The two groups on the right are bologna dropped on a dirty floor and left for five and 50 seconds.

The results show that the microbes needed a little time to grow into bunches big enough to see. On the first day, most of the plates had very few colonies. But by the second and third days, the dishes that had been smeared with eau de bologna sprouted plenty of bacterial colonies. A few microbes even grew on the clean plates swabbed only with distilled water.

From the graph above, it looks like bologna alone grew lots of bacteria. And picking the food up after five seconds appears to have not protected it from microbes. But we can’t make conclusions about the experiment just by looking at the results. We need to use statistics to analyze the data and find out what it all means.

Our hypothesis is that the amount of time on the floor matters: Food picked up after five seconds will have fewer microbial colonies than food picked up after 50 seconds. To test that, we need to compare all six groups at the same time. We’ll analyze the data from day three only.

By day three, the control, on average, grew about nine colonies per plate. In contrast, all the bologna plates grew an average of more than 20 colonies each. Some grew almost 50. (Ewwwww!)

The little Ts sticking out of the bars represent the standard error of the mean. That is how much the data spread. In many of the groups, the data spread a lot. That can make it difficult to tell if there is truly a difference between the groups.

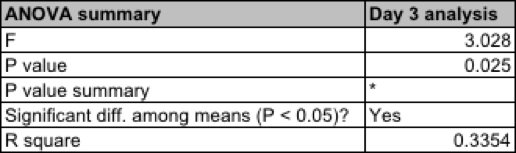

A statistical test called an analysis of variance , or ANOVA, can help here. It’s a test used to compare two or more groups. (For more on ANOVAs, check out this blog post .) GraphPad can calculate the ANOVA. For this data, it generates a table that looks like this:

An ANOVA compares results from one group to those from the other groups. The most important number is the p value (0.025). The p value is the probability of seeing a difference in the number of colonies as large or larger than the one found in my experiment — if there was no actual difference between the groups, and the result happened only by accident. Many scientists accept a p value of 0.05 (five percent) or less to be statistically significant — unlikely to be due to chance. Our p value is less than 0.05. This suggests differences this big would occur only about five percent of the time if the difference wasn’t really there.

But the ANOVA only gives results overall. It says each of the groups are different from each other but not whether there was a difference between the two time periods, five and 50 seconds. A post-hoc test will determine if there are additional differences in the data. GraphPad can calculate this.

The results of the post-hoc test are marked as stars on the graph. Each star represents a p value of less than 0.05 compared to the control. The bologna left on the dirty floor for five seconds had significantly more microbes on it than the control. But so did bologna that was never dropped at all!

What can we conclude? Microbes show up, whether or not food has touched the floor. And time doesn’t matter when it comes to keeping bologna clean.

Any bacteria on that food probably wouldn’t make you sick, fortunately. Our guts are very good at fighting off most germs.

So, can we declare this myth busted? The next post will discuss the limitations of the experiment, and talk about other studies that have taken on the five-second rule.

More Stories from Science News Explores on Health & Medicine

A new type of immune cell may cause lifelong allergies

U.S. lawmakers look for ways to protect kids on social media

9 things to know about lead’s health risks — and how to curb them

Community action helps people cope with Flint’s water woes

Health problems persist in Flint 10 years after water poisoning

Family, friends and community inspired these high school scientists

The teen brain is especially vulnerable to the harms of cannabis

Synthetic biology aims to tackle disease and give cells superpowers

Science News for Students

Designing your own experiment to debunk the ‘five-second rule’

We’ve all been there. You’re excited to take a bite out of your lunch, but then it drops on the floor. You quickly pick it up, but — is it safe to eat?

In Eureka!Lab’s second DIY Science video, science education writer and resident scientist Bethany Brookshire puts the five-second rule to the test. Bethany finds that bacteria don’t really wait for the count of five. If food has fallen, it probably has microbes all over it.

The video and accompanying blog posts walk you through how to design an experiment, grow your own microbes, and analyze results to test whether food left on the floor for only five seconds picks up fewer microbes than food left longer.

View the video below:

Read the blog posts:

- The five-second rule: Designing an experiment

- The five-second rule: Growing germs for science

- The five-second rule: Myth busted?

- The five second rule: Microbes can’t count

Happy experimenting! And hang onto your food.

Related Stories

Lasers, fish-skin bandages and pain-free vaccines: Science News and The New York Times 3rd Annual STEM Writing Contest winners

The New York Times and Science News are accepting submissions for the 2022 STEM Writing Contest!

Star polymers, space origami and singing finches: Science News and The New York Times announce winners of the 2nd Annual STEM Writing Contest

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Curious Cook

The Five-Second Rule Explored, or How Dirty Is That Bologna?

By Harold McGee

- May 9, 2007

A COUPLE of weeks ago I saw a new scientific paper from Clemson University that struck me as both pioneering and hilarious.

Accompanied by six graphs, two tables and equations whose terms include “bologna” and “carpet,” it’s a thorough microbiological study of the five-second rule: the idea that if you pick up a dropped piece of food before you can count to five, it’s O.K. to eat it.

I first heard about the rule from my then-young children and thought it was just a way of having fun at snack time and lunch. My daughter now tells me that fun was part of it, but they knew they were playing with “germs.”

We’re reminded about germs on food whenever there’s an outbreak of E. coli or salmonella, and whenever we read the labels on packages of uncooked meat. But we don’t have much occasion to think about the everyday practice of retrieving and eating dropped pieces of food.

Microbes are everywhere around us, not just on floors. They thrive in wet kitchen sponges and end up on freshly wiped countertops.

As I write this column, on an airplane, I realize that I have removed a chicken sandwich from its protective plastic sleeve and put it down repeatedly on the sleeve’s outer surface, which was meant to protect the sandwich by blocking microbes. What’s on the outer surface? Without the five-second rule on my mind I wouldn’t have thought to wonder.

I learned from the Clemson study that the true pioneer of five-second research was Jillian Clarke, a high-school intern at the University of Illinois in 2003. Ms. Clarke conducted a survey and found that slightly more than half of the men and 70 percent of the women knew of the five-second rule, and many said they followed it.

She did an experiment by contaminating ceramic tiles with E. coli, placing gummy bears and cookies on the tiles for the statutory five seconds, and then analyzing the foods. They had become contaminated with bacteria.

For performing this first test of the five-second rule, Ms. Clarke was recognized by the Annals of Improbable Research with the 2004 Ig Nobel Prize in public health.

It’s not surprising that food dropped onto bacteria would collect some bacteria. But how many? Does it collect more as the seconds tick by? Enough to make you sick?

Prof. Paul L. Dawson and his colleagues at Clemson have now put some numbers on floor-to-food contamination.

Their bacterium of choice was salmonella; the test surfaces were tile, wood flooring and nylon carpet; and the test foods were slices of bread and bologna.

First the researchers measured how long bacteria could survive on the surfaces. They applied salmonella broth in doses of several million bacteria per square centimeter, a number typical of badly contaminated food.

I had thought that most bacteria were sensitive to drying out, but after 24 hours of exposure to the air, thousands of bacteria per square centimeter had survived on the tile and wood, and tens of thousands on the carpet. Hundreds of salmonella were still alive after 28 days.

Professor Dawson and colleagues then placed test food slices onto salmonella-painted surfaces for varying lengths of time, and counted how many live bacteria were transferred to the food.

On surfaces that had been contaminated eight hours earlier, slices of bologna and bread left for five seconds took up from 150 to 8,000 bacteria. Left for a full minute, slices collected about 10 times more than that from the tile and carpet, though a lower number from the wood.

What do these numbers tell us about the five-second rule? Quick retrieval does mean fewer bacteria, but it’s no guarantee of safety. True, Jillian Clarke found that the number of bacteria on the floor at the University of Illinois was so low it couldn’t be measured, and the Clemson researchers resorted to extremely high contamination levels for their tests. But even if a floor — or a countertop, or wrapper — carried only a thousandth the number of bacteria applied by the researchers, the piece of food would be likely to pick up several bacteria.

The infectious dose, the smallest number of bacteria that can actually cause illness, is as few as 10 for some salmonellas, fewer than 100 for the deadly strain of E. coli.

Of course we can never know for sure how many harmful microbes there are on any surface. But we know enough now to formulate the five-second rule, version 2.0: If you drop a piece of food, pick it up quickly, take five seconds to recall that just a few bacteria can make you sick, then take a few more to think about where you dropped it and whether or not it’s worth eating.

Food Safety Issues and How to Avoid Them

Norovirus: The virus, which leads to nausea and vomiting, is spreading and extremely contagious. Here’s what to know about norovirus , and how to protect yourself.

Salmonella: People often get sick with salmonellosis, the infection caused by the bacteria, after eating undercooked meat or other contaminated foods. Here is how to protect yourself .

Listeria: Most people who ingest listeria, bacteria naturally found in the soil, don’t get very sick, if they develop symptoms at all. But certain high-risk individuals can fall seriously ill .

Raw Milk: A growing number of states have allowed the sale of raw milk. Its proponents argue that it has several health benefits, but is it really safe ?

Expiration Dates: When is the right time to throw something out? J. Kenji López-Alt explains why many pantry items remain safe well past their expiration dates .

Washing Produce: To minimize the risk of food poisoning, you really do need to wash your fruit and vegetables before eating them. Luckily, no special produce washes are required .

safe food from farm to fork

A systematic look at the five-second rule: Miranda and Schaffner edition

When I meet someone who asks what I do the conversation usually turns to restaurant grades, foods I avoid and the famed 5-second rule. Most have an opinion that confirms their actions (where benefit may outweigh risk depending on what was dropped).

Rutgers graduate student Robyn Miranda and friend of barfblog (and podcast co-host extraordinaire) Don Schaffner tackled the 5-second rule in a more systematic way and put out a press release today after the paper went through peer-review and was published (cuz that’s how Schaffner rolls). The quick answer to whether the oft-cited risk prevention step is a myth? ‘The five-second rule is a significant oversimplification of what actually happens when bacteria transfer from a surface to food. Bacteria can contaminate instantaneously.’

Turns out bacteria may transfer to candy that has fallen on the floor no matter how fast you pick it up.

Rutgers researchers have disproven the widely accepted notion that it’s OK to scoop up food and eat it within a “safe” five-second window. Donald Schaffner, professor and extension specialist in food science, found that moisture, type of surface and contact time all contribute to cross-contamination. In some instances, the transfer begins in less than one second. Their findings appear online in the American Society for Microbiology’s journal, Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

“The popular notion of the ‘five-second rule’ is that food dropped on the floor, but picked up quickly, is safe to eat because bacteria need time to transfer,” Schaffner said, adding that while the pop culture “rule” has been featured by at least two TV programs, research in peer-reviewed journals is limited.

“We decided to look into this because the practice is so widespread. The topic might appear ‘light’ but we wanted our results backed by solid science,” said Schaffner, who conducted research with Robyn Miranda, a graduate student in his laboratory at the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences, Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

The researchers tested four surfaces – stainless steel, ceramic tile, wood and carpet – and four different foods (watermelon, bread, bread and butter, and gummy candy). They also looked at four different contact times – less than one second, five, 30 and 300 seconds. They used two media – tryptic soy broth or peptone buffer – to grow Enterobacter aerogenes, a nonpathogenic “cousin” of Salmonella naturally occurring in the human digestive system.

Transfer scenarios were evaluated for each surface type, food type, contact time and bacterial prep; surfaces were inoculated with bacteria and allowed to completely dry before food samples were dropped and left to remain for specified periods. All totaled 128 scenarios were replicated 20 times each, yielding 2,560 measurements. Post-transfer surface and food samples were analyzed for contamination.

Not surprisingly, watermelon had the most contamination, gummy candy the least. “Transfer of bacteria from surfaces to food appears to be affected most by moisture,” Schaffner said. “Bacteria don’t have legs, they move with the moisture, and the wetter the food, the higher the risk of transfer. Also, longer food contact times usually result in the transfer of more bacteria from each surface to food.”

Perhaps unexpectedly, carpet has very low transfer rates compared with those of tile and stainless steel, whereas transfer from wood is more variable. “The topography of the surface and food seem to play an important role in bacterial transfer,” Schaffner said.

So while the researchers demonstrate that the five-second rule is “real” in the sense that longer contact time results in more bacterial transfer, it also shows other factors, including the nature of the food and the surface it falls on, are of equal or greater importance.

“The five-second rule is a significant oversimplification of what actually happens when bacteria transfer from a surface to food,” Schaffner said. “Bacteria can contaminate instantaneously.”

The paper can be downloaded here , abstract below.

WORLD: Longer contact times increase cross-contamination of Enterobacter aerogenes from surfaces to food 02.sep.16 Appl. Environ. Microbiol. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.01838-16 Robyn C. Miranda and Donald W. Schaffner Bacterial cross-contamination from surfaces to food can contribute to foodborne disease. The cross-contamination rate of Enterobacter aerogenes was evaluated on household surfaces using scenarios that differed by surface type, food type, contact time (<1, 5, 30 and 300 s), and inoculum matrix (tryptic soy broth or peptone buffer). The surfaces used were stainless steel, tile, wood and carpet. The food types were watermelon, bread, bread with butter and gummy candy. Surfaces (25 cm2) were spot inoculated with 1 ml of inoculum and allowed to dry for 5 h, yielding an approximate concentration of 107 CFU/surface. Foods (with 16 cm2 contact area) were dropped on the surfaces from a height of 12.5 cm and left to rest as appropriate. Post transfer surfaces and foods were placed in sterile filter bags and homogenized or massaged, diluted and plated on tryptic soy agar. The transfer rate was quantified as the log % transfer from the surface to the food. Contact time, food and surface type all had a highly significant effect (P<0.000001) on log % transfer of bacteria. The inoculum matrix (TSB or peptone buffer) also had a significant effect on transfer (P = 0.013), and most interaction terms were significant. More bacteria transferred to watermelon (~0.2-97%) relative to other foods, while fewer bacteria transferred to gummy candy (~0.1-62%). Transfer of bacteria to bread (~0.02-94%) and bread with butter (~0.02-82%) were similar, and transfer rates under a given set of condition were more variable compared with watermelon and gummy candy.

Science Friday

- Science Diction

- Best Of 2019

The Origin Of ‘The Five-Second Rule’

It has to do with Genghis Khan and Julia Child.

First Known Use:

The first written reference to a “rule” about the acceptability of eating dropped food appeared in 1995 —but the household guideline was already long in the making.

Whether you call it the five-second rule, three-second rule, or the ____-second rule, you know what this rule is. Someone drops a tasty morsel of food on the ground and scoops it right back up, declaring that, according to the “rule,” there was no time for the bacteria to glom onto the treat. As usual, the history of this idiom is a little more complicated than that, and the science is, too. Is there any scientific validity to the five-second rule?

Genghis Khan, Julia Child, And The Five-Second Rule

The five-second rule as we know it today has murky origins. The book Did You Just Eat That? by food scientist Paul Dawson and food microbiologist Brian Sheldon traces the origins to legends around Genghis Khan. The Mongol ruler is rumored to have implemented the “Khan Rule” at his banquets. “If food fell on the floor, it could stay there as long as Khan allowed,” write Dawson and Sheldon. The idea was that “food prepared for Khan was so special that it would be good for anyone to eat no matter what.”

“In reality,” they write, “people had little basic knowledge of microorganisms and their relationship to human illness until much later in our history. Thus, eating dropped food was probably not taboo before we came to this understanding. People could not see the bacteria, so they thought wiping off any visible dirt made everything fine.”

Roughly six centuries after Khan’s death, germ theory evolved into, as the Encyclopedia Britannica writes, “perhaps the overarching medical advance of the 19th century.” Researchers determined that tiny, invisible microorganisms caused certain diseases and infections—and French chemist Louis Pasteur proved that those same kinds of microorganisms are behind both wine fermentation and the souring of milk. But despite knowing that germs are everywhere, it can still be tough to walk away from a tempting treat that slipped through one’s fingers.

We see the rule pop up once again in a 1963 episode of Julia Child’s cooking show The French Chef , which may have helped canonize the attitude, if not the phrase, into popular imagination. The famous chef attempted to flip a potato pancake in a pan, but she missed, and the pancake landed squarely on the stovetop.

“When I flipped it, I didn’t have the courage to do it the way I should’ve,” Child said. “But you can always pick it up if you’re alone in the kitchen. Who is going to see?”

The flopped pancake sits on the stovetop for about four seconds before Child tosses it back into the pan, but by the time the phrase begins to solidify and appear in print, people take their own liberties with the exact amount of acceptable seconds. According to the Oxford English Dictionary , the first mention in print of some sort of rule came from the 1995 novel Wanted: Rowing Coach , which referenced a “twenty-second rule.” A few years later, in the 2001 animated film Osmosis Jones , a character follows the “ten-second rule” and eats a germ-infested egg, which sends his body’s immune system into disarray.

So, Is The Five-Second Rule Actually Real?

Robyn Miranda, a Ph.D candidate in food science at Rutgers University, published a study in Applied and Environmental Microbiology with her adviser that scientifically investigated the validity of the five-second rule.

“It was not what I expected to do for my master’s,” she says. “We saw this as a really important opportunity to look at this rule that people truly follow, that consumers really use. So, let’s see if this matters, from a public health standpoint.”

Miranda stocked up on four different food types: watermelon, bread, bread and butter, and gummy candy. Then, she methodically dropped each food onto one of four surfaces typically found in kitchens—stainless steel, tile, wood, and carpet—and let each food item sit for exactly less than a second, five seconds, 30 seconds, and five minutes to measure bacterial transmission. Miranda and a team of undergraduates did 20 replicates of each food, on each surface, for each length of time, over the course of six months. “I’m not going to lie; doing the experiments lost its luster after a while,” she says. “But the results were very interesting.”

The Science Behind The Five-Second Rule

Wearing a food seat belt.

While microorganisms are to blame for infections, not all bacteria are created equal.

“We carry four pounds of bacteria around with us on our bodies all the time,” Paul Dawson tells Science Friday. “And we have more bacterial cells in and on our body than we have our human cells—so we’re kind of in symbiotic relationship with it. And we’re more and more finding they are part of our health, the delicate balance there, so to speak.”

There is some truth to the idea that exposure to certain bacteria and compounds can help build immunity, says Dawson. But we also know that people can become seriously sick from certain infections, so random exposure may not be the best practice. Dawson compares eating food off the floor to wearing a seatbelt: “You probably could do both of those your whole life and never be injured or get sick, but we know with the seat belt that if you have an accident or there is bacteria there, you’re going to be exposed to it.”

“Speaking specifically about the five-second rule and when eating food off the floor, probably in reality there’s not much risk in that,” he says. “But I don’t know if there’s much to be gained either though, as far as immunity.”

But often, it’s not immunity that’s in the forefront of people’s minds when a morsel hits the floor.

“I don’t eat food off the floor, but I also don’t drop food on the floor,” says Robyn Miranda. “But if I [did], it would depend.” Watermelon? No way, she says. Skittles? Maybe. “I guess you’d be surprised what people will do for a food that they care about.”

Sources And Further Reading

- Special thanks to Robyn Miranda and Paul Dawson

- Did You Just Eat That? Two Scientists Explore Double-Dipping, the Five-Second Rule, and Other Food Myths in the Lab by Paul Dawson and Brian Sheldon

- “Longer Contact Times Increase Cross-Contamination of Enterobacter aerogenes from Surfaces to Food” (American Society for Microbiology: Applied and Environmental Microbiology)

- “History of medicine: Verification of the germ theory” (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- The Oxford English Dictionary

Meet the Writer

About johanna mayer.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

Explore More

The origin of the word ‘tuberculosis’.

Why did we stop calling the disease 'consumption'?

What Happens When You Double Dip That Chip?

Does double-dipping a chip really infect the dip? Is the five-second rule real? Plus, a look at other food myths.

Privacy Overview

- All Publications

- Priorities Magazine Spring 2018

- The Next Plague and How Science Will Stop It

- Priorities Magazine Winter 2018

- Priorities Magazine Fall 2017

- Little Black Book of Junk Science

- Priorities Magazine Winter 2017

- Should You Worry About Artificial Flavors Or Colors?

- Should You Worry About Artificial Sweeteners?

- Summer Health and Safety Tips

- How Toxic Terrorists Scare You With Science Terms

- Adult Immunization: The Need for Enhanced Utilization

- Should You Worry About Salt?

- Priorities Magazine Spring 2016

- IARC Diesel Exhaust & Lung Cancer: An Analysis

- Teflon and Human Health: Do the Charges Stick?

- Helping Smokers Quit: The Science Behind Tobacco Harm Reduction

- Irradiated Foods

- Foods Are Not Cigarettes: Why Tobacco Lawsuits Are Not a Model for Obesity Lawsuits

- The Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis: A Review

- Are "Low Dose" Health Effects of Chemicals Real?

- The Effects of Nicotine on Human Health

- Traditional Holiday Dinner Replete with Natural Carcinogens - Even Organic Thanksgiving Dinners

- A Primer On Dental Care: Quality and Quackery

- Nuclear Energy and Health And the Benefits of Low-Dose Radiation Hormesis

- Priorities in Caring for Your Children: A Primer for Parents

- Endocrine Disrupters: A Scientific Perspective

- Good Stories, Bad Science: A Guide for Journalists to the Health Claims of "Consumer Activist" Groups

- A Comparison of the Health Effects of Alcohol Consumption and Tobacco Use in America

- Moderate Alcohol Consumption and Health

- Irradiated Foods Fifth Edition

- Media/Contact

- Write For Us

When the '5-Second Rule' Works (and When it Doesn't)

Ever wonder if it’s really safe to eat food quickly after dropping it on the ground?

Science suggests that it may actually be alright to do so -- however, there are conditions -- because it all depends on what you drop and where you drop it. But given the proper circumstances, you can have reasonable faith that the so-called "5-second rule” works to keep illness at bay.

That's also the view presented in a report on the Discovery Science Channel called the “The Quick and the Curious.” And, as you might expect, time plays a role in determining what's considered edible, and what's considered risky.

E. coli , Salmonella and Listeria thrive in wet places, and they suck up nutrient-rich water needed in order to reproduce. So when food is left on the ground or dirty surface for 30 seconds, according to Discovery 10 times the bacteria jumps on moist food than if left for just three seconds. But as far as bacteria goes, the 5-second rule stands for food hitting dry surfaces, according to veteran San Diego County health inspector Robert Romaine.

“If the food is dry, and there’s no stickiness to it, it’s less likely that bacteria will stick to it,” Romaine said. “If it’s dry food, then we’re just talking about filth, like hair or whatever is on the soles of shoes.” What this really means is that you're dealing with what you can see -- and can possibly brush or blow off -- as opposed to bacteria which you can't see.

And then there are surfaces. The Discovery video report also stated that some bacteria will always climb onto fallen food, but that fewer germs can migrate from rugs than linoleum. That's due to the small, separated tufts on rugs, upon which less surface area of food makes contact.

Clemson University Professor Paul Dawson backed up this claim in a 2006 study in which he placed bologna and bread on Salmonella -inoculated squares of carpet, tile and wood for various amounts of time. He found that 48 to 70 percent of the bacteria attached to the food from the tile and wood. Comparatively, the food was found to have had less than one percent of the bacteria from the carpet.

According to Dawson , "It looks like what’s at issue is less how long your food languishes on the floor and much more how infested with bacteria that patch of floor happens to be." A similar study from Aston University found similar results. This U.K. study found that 87 percent of people asked had no problem eating fallen food, and that 55 percent were women.

One should still display caution, Ruth Frechman, MA, RD, tells WebMD. "Bacteria are all over the place, and 10 types -- including E. coli -- cause foodborne illnesses, such as fever, diarrhea, and flu-like symptoms."

About 76 million Americans contract foodborne illnesses each year, according to the CDC . And about 300,000 are hospitalized, while 5,000 die.

"Err on the side of safety," Frechman says. "At least, wash it first."

View the discussion thread.

By ACSH Staff

Latest from ACSH Staff :

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The 5 Second Rule Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday Courage

Related Papers

IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science

Fabio Quaranta

Stanley Sheft

: This three-year research project had the basic aim of understanding the role of binaural hearing in the ability to segregate multiple sound sources in complex sound environments. There were four main projects undertaken over the past three years: (1) To determine the role of binaural cues in sound source identification, (2) To determine the role of spatial separation in processing amplitude modulation, (3) To develop and validate a paradigm for studying analytic and synthetic processing of multiple sound sources, (4) To investigate the role of echoes on the ability of listeners to locate and determine the sources of sound. We found that binaural cues do aid in sound source identification, but that the effects were much greater for three rather than for two sound sources. The ability to process amplitude modulation is aided, but only slightly so, by spatially separating the modulated sources. We developed SALT (Synthetic and Analytic Listening Task) for studying processing of multi...

Israel Journal of Health Policy Research

ifat vainer

Vaccinating children against influenza has shown both direct and indirect beneficial effects. However, despite being offered free of charge, childhood influenza vaccine coverage in Israel has been low. Our objective was to evaluate the factors associated with childhood influenza vaccination in Israel. A cross-sectional language-specific telephone survey was conducted among adults 18 years or older, to examine childhood influenza vaccination practices and their associations with socio-demographic and relevant health variables. We further explored the reasons for these practices among parents. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with childhood influenza vaccine acceptance. Of a total of 6518 individuals contacted by mobile phone, 1165 eligible parents, ≥18 years old with children 1-18 years of age, were interviewed, and 1040 of them completed the survey successfully. Overall, factors associated with childhood influenza vaccination were younger chil...

Channa Rajanayaka

ion from surface and groundwater bodies alters river flow regimes. The economic and social benefits of abstraction need to be balanced against their consequences for hydrology dependent ecological functions, ecosystem services, cultural values and recreation. However, impacts of an abstraction on flow regimes are often assessed in isolation and so cumulative impacts of many spatially distributed abstractions on the catchment are not understood. While spatially distributed, high-resolution model(s) (e.g. MODFLOW) can be developed to understand the cumulative impacts of abstractions, this is cost prohibitive and the demand for data is high (e.g., system properties, hydroclimatic) to develop such a model at regional scales and, further, such site specific models cannot be transferred to other spatial locations. We have developed a model to estimate cumulative streamflow depletion at given locations of a stream network resulting from both surface and groundwater abstractions. The surfac...

Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Pediatrics

Kamil Orhan

Annals of Global Health

Keamogetse Setlhare

Ahi Evran Üniversitesi Kırşehir Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi

Tolga TOPCUBAŞI

Edgar Enrique Velásquez Camelo

The aim of the paper is to reflect on the cathartic function of literary works as a crucial element in the hermeneutic process. It is based on the contributions of Gadamer and Ricoeur concerning the setting up of the world of the text in relation to the world of the reader within the context of literature. The paper argues that when we understand a work of art, we understand ourselves in a better way and different horizons of understanding are established due to the applicability of the literary object. In fact, the interpretative process of a literary work occurs when an understanding of the world of the text is enabled by the world of the reader, that is, when the interpreter is able to establish a link between the experiences described in the literary work and her own experiences. That is precisely why it is so important to understand the human being in relation to its own time, because it makes possible to develop interpretative processes which enable the cathartic function of t...

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

Khalid Mahmoud

Background Whilst the impact of Covid-19 infection in pregnant women has been examined, there is a scarcity of data on pregnant women in the Middle East. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine the impact of Covid-19 infection on pregnant women in the United Arab Emirates population. Methods A case-control study was carried out to compare the clinical course and outcome of pregnancy in 79 pregnant women with Covid-19 and 85 non-pregnant women with Covid-19 admitted to Latifa Hospital in Dubai between March and June 2020. Results Although Pregnant women presented with fewer symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, and shortness of breath compared to non-pregnant women; yet they ran a much more severe course of illness. On admission, 12/79 (15.2%) Vs 2/85 (2.4%) had a chest radiograph score [on a scale 1-6] of ≥3 (p-value = 0.0039). On discharge, 6/79 (7.6%) Vs 1/85 (1.2%) had a score ≥3 (p-value = 0.0438). They also had much higher levels of laboratory indicators of severity wi...

Anna Marciniuk-Kluska

The paper elaborates on the issues showing the need for the development of tourism at the level of local government units, i.e. communes and districts. Special attention is paid to the benefits deriving from the development of tourism and the possibility of creating conditions facilitating tourism development by communes. A very important element in the tourism development at the level of a commune or district is the positive attitude of local authorities, bodies which can strongly and diversely support the development of tourism. This can be done by adequate promotion, especially by communes and tourism organisations. Local area natural values or protected landscape areas are only two of many factors significant in the development of tourism in a given commune.

RELATED PAPERS

Juan Camilo Rodríguez Gómez

Zaiton Osman

Diritto Pubblico Europeo Rassegna online

Gennaro Ferraiuolo

Észak-magyarországi stratégiai füzetek

Blaga Agnes

Case Reports in Pediatrics

Sourabh Verma

Jose Luis Muñoz

Agon Rrezja

Higher Education in Asia: Quality, Excellence and Governance

Lilian Mayagoitia

Multimedia Tools and Applications

Annals of Nuclear Energy

Waclaw Gudowski

IFAC Proceedings Volumes

Nedjeljko Peric

Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France

Jean-louis Olivet

Journal of Language and Education

Pilar Gerns

Neurophysiology

Natalia Yatsenko

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

More results...

Researchers Reveal the Truth About the ‘Five Second Rule’

- September 26, 2016

Unfortunately, researchers have now proven that the ‘five second rule’ for eating food off the floor is, in fact, not scientifically accurate.

The time it takes bacteria to transfer onto food can actually be less than one second, according to researchers at Rutgers University led by professor Donald Schaffner, an extension specialist in food science.

A ‘Pop Culture’ Myth

“The popular notion of the ‘five-second rule’ is that food dropped on the floor, but picked up quickly, is safe to eat because bacteria need time to transfer,” said Professor Schaffner.

“We decided to look into this because the practice is so widespread. The topic might appear ‘light’ but we wanted our results backed by solid science,” he added.

Their first findings confirmed that moisture, surface type and the fabled contact time all have a part to play in cross contamination.

Those variables were explored further by testing four food types (watermelon, bread, bread and butter, and gummy sweets), four surfaces (ceramic tiles, wood, stainless steel and carpet) and four contact times (less than one second, 5 seconds, 30 seconds, 300 seconds) at the university labs in New Brunswick.

So what did they find?

Watermelon was the most easily contaminated food, which led researchers to conclude that moisture is the strongest player in terms of cross contamination. If you do drop your watermelon, though, make sure it’s on a carpet, which had lower transfer rates than stainless steel and ceramic tiles. Gummy sweets were found to be the safest food to drop.