Italy’s Food: Traditional Italian Food Recipes

Introduction, food and beverages commonly used, meal patterns and eating customs/habits, diet evaluation, salt, fiber, and fat intake, food for special occasions, cooking methods, additional facts.

Italian cuisine is famous around the world for its delicious and healthy food. It includes thousands of varieties of recipes for different dishes with various ingredients. In Italy, culinary traditions are passed down from generation to generation. One of the features of Italy is the different culinary traditions in each region of the country, which have been formed over the centuries. Italian cuisine occupies one of the first places in terms of the quality and the beneficial properties of the dishes. The distinguishing feature of Italy and its cuisine is in the cooking process and the culture of the meal.

The common Italian foods are pizza, typical appetizers, and desserts of Italian cuisine. Appetizers on the Italian table are mainly various types of cheese and frittata, that is, fried appetizers. Other popular foods are lasagna, minestrone, tortellini, ravioli, risotto, spaghetti and carpaccio. Common beverages in Italy are different sorts of regional wines. Wine production is mainly carried out in the country’s north, where the world-famous Chianti and the slightly less popular Marsala wine are produced. Of course, not only is wine consumed in Italy, but coffee is also widely drunk with meals – espresso, cappuccino, or latte.

It is not customary in Italy to eat in a hurry, so “fast foods” are not popular there. For breakfast in Italy, it is customary to drink natural coffee or latte. Lunch is full of various dishes and includes an appetizer, a first course, a second course, fruit, and the usual coffee. The first course includes pasta, risotto, or vegetable soup, and the second – meat, fish, or cheese with a vegetable side dish. Almost always, lunch and dinner are accompanied by wine and end with a fruit and fennel dessert. Italians often dine out, so the restaurant culture is very developed there.

Italian cuisine is very simple and much lighter than US food since it uses mostly simple ingredients. Italian diet is one of the healthiest and most balanced, and the principles of Italian nutrition underlie the Mediterranean diet (Artese et al., 2021). Italians use wheat bread, not toast bread, which is popular in the US. In general, when compared to the US, the Italian diet is healthier because it contains natural products. Commonly, US cafes and households favor such foods as fast-food, bacon fried in processed oil, sweets, and beverages that contain a high amount of sugar. Dietary restrictions in the Italian diet include fried, oily foods, low-quality bread products, and processed sugars.

An Italian diet contains a high amount of fiber products in its cuisine. Fiber, when eaten excessively, may lead to reduced sugar levels in the blood and flatulence (Ocvirk et al., 2019). Fats also take place in the Italian diet, mostly in olive oil. However, there are not many processed oils in the cuisine, which is beneficial for health. Italians do not usually use too much salt in their dishes since they add more different seasonings. Salt can retain moisture in the human body; that is why it is important to maintain enough amount of salt consumed. Lack of salt can lead to dehydration of the body; in severe cases, hyponatremia can develop with a lack of salt in the body.

The festive menu in Italy differs from the everyday one and includes special dishes for every occasion. For example, on Christmas Eve, fish delights are served on the table: oysters, carpaccio from various seafood, grilled eel or swordfish, sea bream, baked trout, etc. Side dishes of vegetables and potatoes accompany everything. The special occasion meal ends with desserts named Pandoro or Panettone. Yet on Christmas itself, different dishes with meat are served. Various sorts of wines are also served on special occasions and celebrations.

Many dishes of Italian cuisine are prepared with wine, stewed, soaked in wine, and marinated. Most Italian cuisine recipes require minimal heat treatment and a simple preparation method. In this way, one can feel the natural taste of the products. Most commonly, dishes in Italy are boiled, stewed, baked, or smoked. For instance, pasta products are boiled, meat is smoked or stewed, and dishes such as pizza and desserts are baked in ovens. However, cooking methods vary from region to house or even from house to house.

One of the features of Italy is the different culinary traditions in each region of the country, which have been formed over the centuries based on common products in a particular area. Italians prepare very tasty natural ice cream, numbering several dozen types. Many wines are produced in Italy – red, rose, white, dry, semi-dry, carbonated, etc. As a rule, Italians rarely go for a combination of seafood and cheese. In general, they are very zealous about violating the canons of Italian cuisine. However, commonly, true Italian cuisine follows a strict recipe adopted in one region, a city, and sometimes even a family.

In conclusion, Italian cuisine is not only popular around the world for the unique taste of the dishes but also for its healthy approach. The diet is natural and light for the body, including whole products and simple cooking methods. Eating customs and habits in Italy are also special, which can be traced from the common eating trends in the region. Italian cuisine is rich in different types of foods and beverages, which are now beloved by many other countries. Recipes of dishes can vary in different parts of Italy, mostly because of geographical factors. Nevertheless, each dish tends to have some peculiarities in cooking and selection of ingredients.

Artese, M. T., Ciocca, G., & Gagliardi, I. (2021). Analysis of traditional Italian food recipes: Experiments and results. In International Conference on Pattern Recognition (pp. 677-690). Springer, Cham.

Ocvirk, S., Wilson, A. S., Appolonia, C. N., Thomas, T. K., & O’Keefe, S. J. (2019). Fiber, fat, and colorectal cancer: New insight into modifiable dietary risk factors. Current gastroenterology reports , 21 (11), 1-7.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2023, July 21). Italy’s Food: Traditional Italian Food Recipes. https://studycorgi.com/italys-food-traditional-italian-food-recipes/

"Italy’s Food: Traditional Italian Food Recipes." StudyCorgi , 21 July 2023, studycorgi.com/italys-food-traditional-italian-food-recipes/.

StudyCorgi . (2023) 'Italy’s Food: Traditional Italian Food Recipes'. 21 July.

1. StudyCorgi . "Italy’s Food: Traditional Italian Food Recipes." July 21, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/italys-food-traditional-italian-food-recipes/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Italy’s Food: Traditional Italian Food Recipes." July 21, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/italys-food-traditional-italian-food-recipes/.

StudyCorgi . 2023. "Italy’s Food: Traditional Italian Food Recipes." July 21, 2023. https://studycorgi.com/italys-food-traditional-italian-food-recipes/.

This paper, “Italy’s Food: Traditional Italian Food Recipes”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: July 21, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Longreads : The best longform stories on the web

Buon Appetito: A Reading List on Italian Food

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Mastodon (Opens in new window)

This story was funded by our members. Join Longreads and help us to support more writers.

I came to this topic as an eater first. My partner and I fell in love through food. We met during the pandemic and got to know each other through long walks and home-cooked meals. On an early date, she put a glistening mound of pasta in front of me and I thought how lucky I was to have fallen for an Italian. (She was born and raised in Rome.)

Most Italians have a strident pride in their cuisine; a passion which occasionally verges on the maniacal. The food and beverage industry makes up a quarter of Italy’s GDP and a substantial portion of its tourist draw. Food is tightly bound with ideas of national identity and politicians often rely on a kind of gastronationalism. (When running for election, current Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni posted a video of herself making tortellini with a stereotypical Italian nonna.)

And it’s not just Italians who hold this enthusiasm—Italian cuisine is one of the most popular in the world. Home cooks love to prepare Italy’s dishes , and about one-eighth of restaurants in the U.S. serve Italian food. Shows like Stanley Tucci’s Searching for Italy and the Netflix series From Scratch highlight just how ravenous audiences are for luscious, almost erotic depictions of Italian food.

But in researching this list, I’ve learned that beneath the promotional language and tired clichés, Italian food has a complex and often contradictory history. Academics question the true origin of classic dishes like carbonara ; migration from Italy to the U.S. makes it almost impossible to disentangle the two gastronomic traditions.

Italians often obsess over this cultural purity. When Italian chef Gino D’Acampo appeared on morning television in the UK a decade ago, he was horrified by the suggestion that you could substitute ham in carbonara. “If my grandmother had wheels, she would have been a bike,” D’Acampo responded incredulously. The clip went viral, bolstering the stereotype that Italians can be fussy about their food. But the history of Italian cuisine—like the food of any nation—is a melting pot of influences.

But what of the future? Migration patterns, together with demographic trends and climate change, mean that the cuisine must adapt. Since 2003, Europe has experienced an unprecedented number of heatwaves, prompting Italy’s largest farmers’ union to estimate that almost a third of national agricultural production is now threatened by climate change. Italian food—so rooted in tradition and adamant in its authenticity—will have to change.

But for now, I’m excited to visit Rome for the holidays and soak up the city’s culinary delights: creamy cacio e pepe, indulgent layers of tiramisu, and moreish slices of pizza. I’ll photograph the food, luxuriate in it, and come home with a suitcase full of olive oil and cheese. This time, I hope to enjoy the food while knowing more about the context that underpins it. Like the best Italian dishes, this topic is rich with complexity and nuance. So please devour this collection of articles that complicate the understanding of Italian food and what it means both within Italy’s borders and beyond.

Everything I, an Italian, Thought I Knew About Italian Food is Wrong (Marianna Giusti, Financial Times , March 2023)

This Italian-language podcast , hosted by Alberto Grandi and Daniele Soffiati, also explores the true history of Italian food and aims to separate marketing from truth.

In this fascinating piece, Italian journalist Marianna Giusti aims to uncover the truth about classic Italian dishes like carbonara, tiramisu, and panettone—which are celebrated for their authenticity despite being relatively recent inventions. She speaks with older family members and friends from across Southern Italy, asking about the food they ate as children (lots of beans and potatoes) and how it contrasts with the food on menus today.

Inaccuracies about the origins of Italian food may be considered harmless—if it wasn’t for how gastronationalism influences Italian politics and culture. She cites the example of the archbishop of Bologna, Matteo Zuppi, suggesting that pork-free “welcome tortellini” be added to the menu for the San Petronio feast. What was intended as a gesture of inclusion to communities that don’t eat pork, was slammed by far-right Lega party leader Matteo Salvini. “They’re trying to erase our history, our culture,” he said. To me, food is one of life’s great unifiers. I love to bring people together around food, but just as often, food is used to divide people. This piece made me reconsider what I thought I understood about Italian food and think critically about who and what is welcome at the table.

It’s all about identity,” Grandi tells me between mouthfuls of osso buco bottoncini. He is a devotee of Eric Hobsbawm, the British Marxist historian who wrote about what he called the invention of tradition. “When a community finds itself deprived of its sense of identity, because of whatever historical shock or fracture with its past, it invents traditions to act as founding myths,” Grandi says.

There Is No Such Thing As Italian Food (John Last, Noema , December 2022)

In this provocatively-titled piece, journalist John Last examines how climate change and immigration patterns are changing food in Italy. It examines how ingredients from abroad and the labor of migrants were used to build one of the world’s most loved cuisines. It also cites a study that found that the role of immigrants in Italy’s farming and culinary sectors has been systematically ignored. Italian food is often celebrated for connecting eaters with unadulterated, authentic cuisine. The reality is much more complicated. I enjoyed how this deeply-reported essay challenges ideas of culinary purity and questions who that narrative excludes. I was interested to read how Italy’s microclimates produce regional specialities, and how they will be forced to adapt due to climate change. If you’re curious about the future of Italian cuisine, this is the essay for you! It has also been anthologized in Best American Food Writing 2023 for its examination of how food shapes our culture.

It’s this obsessive focus on the intersection of food and local identity that defines Italy’s culinary culture, one that is at once prized the world over and insular in the extreme. After all, campanilismo might be less charitably translated as “provincialism” — a kind of defensive small-mindedness hostile to outside influence and change.

What the Hole Is Going On? The Very Real, Totally Bizarre Bucatini Shortage of 2020 (Rachel Handler, Grub Street , December 2020)

If you’re interested in the pasta-making process or more pandemic-era pasta content, I recommend Mission Impastable from The Sporkful .

The early months of the pandemic were characterized by lockdowns, widespread anxiety, and a national pasta shortage . In this funny, engaging piece written by the self-described “Bernstein of Bucatini,” I learned why some pasta shapes were especially difficult to find due to production challenges. This piece is an enjoyable, twisty romp that points to the sensual delight of pasta during a dark time.

I’d like to go a step further and praise its innate bounciness and personality. If you boil bucatini for 50 percent of the time the box tells you to, cooking it perfectly al dente, you will experience a textural experience like nothing else you have encountered in your natural life. When cooked correctly, bucatini bites back. It is a responsive noodle. It is a self-aware noodle. In these times, when human social interaction carries with it the possible price of illness, bucatini offers an alternative: a social interaction with a pasta.

America, Pizza Hut, and Me (Jaya Saxena, Eater , March 2016)

I really enjoyed this thoughtful personal essay about a young girl’s obsession with Pizza Hut and the influence of food on her identity. The author questions her intersecting heritage: she’s a mixed kid with an Indian father and a white mother, a New Yorker who craves stuffed crusts in Pizza Hut rather than an “authentic” dollar slice, and a pre-teen who wants to eat “white food” while her family enjoys soupy dal and potatoes flavored with cumin and turmeric. This piece is also a useful primer on the history of Italians in America, tracing the path from “other” to mainstream acceptability.

I was half Indian, half white, and all New Yorker. In simple assimilation calculus, going to Pizza Hut with my Indian grandparents in Fort Lee should have earned me points for eating in real life what the cool kids were eating in commercials. And yet, I was still a New Yorker: My ideal sense of self was white, but worldly, opinionated, and judgmental.

Finding Comfort and Escape in Marcella Hazan’s Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking (A. Cerisse Cohen, Lit Hub , November 2022)

I loved this essay about how the author learned to cook during the pandemic and the comfort she found in the reassuring, authoritative voice of Marcella Hazan. The piece vividly describes the flavors of Italian food (“mellow, gentle, comfortable”) and the solace found in cookbooks at a time of unprecedented uncertainty. Before learning to cook, the author considered it a domestic task inextricably linked with traditional notions of femininity and heterosexual marriage. But Hazan, who is widely considered to be the doyenne of Italian cuisine, teaches her that cooking for herself and her chosen family is an essential element of survival, not only literally but existentially. This essay brought me back to the early days of 2020. As the pandemic spiraled out of control, I found my equilibrium through brisk morning walks and the comfort of a pot bubbling on the stove. I still cook most days. Sometimes, it’s a pleasure. More often, it’s a chore. For me, this beautiful essay evoked the visceral, bodily demands of appetite and how satiating them can provide not just culinary satisfaction, but a feeling of peace and wellbeing.

Hazan helped me see that nourishing oneself, and sharing a family meal, is simply foundational. To privilege invention and labor outside the kitchen, but not inside it, is to play into patriarchal distinctions of value. Hazan herself was a cook, an educator, and an incredible creative success. She remains influential for many contemporary cooks. Her adoration of the anchovy—“Of all the ingredients used in Italian cooking, none produces headier flavor than anchovies. It is an exceptionally adaptable flavor”—foreshadows the long reign of Alison Roman. Her careful ideas about layering flavors and her scientific approach to the kitchen find their echoes in the methodologies of Samin Nosrat (who, in her blurb for the new book, also credits Hazan with beginning her obsession with the bay leaf).

Eating the Arab Roots of Sicilian Cuisine (Adam Leith Gollner, Saveur , March 2016)

If you’d like to continue your study of Sicilian cuisine and perhaps try a recipe, you might enjoy this Salon piece about the author’s love of oily fish, simple pasta, and bright flavors.

My partner and I recently returned from a holiday in Sicily. The island is considered to be a melting pot of North African, Arab, French, Spanish, and other cultures—which for me, was best understood through the food. We enjoyed regional delicacies like deep-fried lasagne, cookies made with beef and chocolate, and cremolata, a sherbet-like dessert that originated in Arab cuisine. It was a delight to remember the trip while reading this mouth-watering travel essay which aims to disentangle how Italian and Arab culinary history mixes on the island. What begins as an academic question quickly becomes a catalog of exquisite meals as the author explores the island’s rich, colonial past through its food. He traces the ingredients that are core to Italian cuisine—including the durum wheat used to make pasta—to migrants who arrived on Sicily’s shores and “gifted this land with what’s sometimes known as Cucina Arabo-Siculo.”

Sicily has had so many conquerors, and there’s simply no way to pull apart all the intermingling strands of culture in order to ascertain what is precisely “Italian” and what’s “Arab” and what’s not anything of the kind. At a certain point—ideally sometime after having a homemade seafood couscous lunch in Ortigia and sampling the life-changing pistachio ice cream at Caffetteria Luca in Bronte—you have to give up trying to isolate the various influences and accept that countless aspects of life in Sicily have been informed by Arab culture in some way. It’s deep and apparent and meaningful, but it’s also a cloud of influence as dense and intangible as the lemon gelato sky that greeted me upon my arrival.

Clare Egan is a queer freelance writer based in Dublin. She writes about food (among other things) for her newsletter and is working on her first book.

Editor: Carolyn Wells

Copyeditor: Krista Stevens

Support Longreads

By clicking submit, you agree to share your email address with the site owner and Mailchimp to receive marketing, updates, and other emails from the site owner. Use the unsubscribe link in those emails to opt out at any time.

Life in Italy, Italian Language, Italian Culture, Italy News, Tourism News, Italian Food

The History of Italian Cuisine I

It is easy to love good food , and we Italians know a couple of things about it. When you enjoy cooking, you become acquainted with ingredients and flavors with a pleasurable delight. You get to know how they mix with each other, which type of scent their fragrance produces, and how they will taste once they touch your tongue. Ah… food : like poetry and painting, it’s impossible to resist the beauty, forms, and colors it creates when it’s spread out on a table and, of course, it’s even harder to refrain from tasting it. In this article, we’re going to review the history of Italian cuisine from the Roman Empire to the Middle Ages.

The History of Italian Cuisine

When you love food, there are two things you really want to do: eat it and make it. That’s why it’s nice to have a well-furnished kitchen, and plenty of interesting recipes to try, as well as a gang of good friends, to invite over to justify your spending every single weekend surrounded by pots and pans, making your best impression of a domestic goddess/god.

But you know what, there’s something we barely stop thinking about when in the kitchen, the history behind what we’re making and eating. Have you ever thought of it? You guys, on the other side of the pond, are usually more aware of it, as your cuisine is a delicious melting pot of flavors and cultures hailing from every corner of the Earth, the heritage and history of which is usually well rooted into the community.

In Italy, things are a bit different: we usually care deeply and lovingly about our family’s cooking history. Grandmas and moms’ recipes are passed on with care and pride, a symbol itself of one’s own heritage and roots. Some of us are more aware than others of regional characteristics typical of each dish. It is not usual though, when it comes to the kitchen, to look further back than a couple of generations. Our knowledge of why we cook in a certain way and why we eat certain things is normally based on oral sources (our elders) and therefore has a limited time span.

The history of Italian cuisine , however, is as long and rich as the country’s history itself, its origins laying deep into the ancestral history of Rome, its people, and its political, cultural, and social power. Italian cuisine has evolved and changed following the evolution and the changes of Italy itself throughout centuries of wars, cultural mutations, and contacts: it’s a history as rich, colorful, and fascinating as the most amazing of recipes.

This is what we’re going to tell you today: a tale of food, traditions, kings and warriors, the centuries-long tale of Italian kitchens . The history of Italian cuisine.

The Roman Empire and the early Middle Ages

Our ancestors, the Romans , loved feasting on food: the banquet was not simply a moment of social conviviality, but also the place where new dishes were served and tried. The Empire embraced the flavors and ingredients of many of the lands it had conquered: spices from the Middle East, fish from the shores of the Mediterranea, and cereals from the fertile plains of North Africa; Imperial Rome was the ultimate fusion cuisine hot spot. The Romans, though, contrarily to how we’re today, liked complex, intricated flavors and their dishes often required sophisticated preparation techniques. Ostrich meat, fish sauces, roasted game, all watered by liters of red wine mixed with honey and water, never failed to appear on the table of Rome’s rich and famous.

Of course: we’re talking about the jet-set here, certainly not about the majority of people, who very much, on the other hand, based their diet on the simple union of three things (and the products made of them): the vine, the olive, and cereals. This was called Mediterranean Triad and is still today considered central to the diet known worldwide as the Mediterranean diet . Wine, olive oil, and bread, then, plus healthy helpings of vegetables, legumes, and cheese: this is what the people of Rome would eat on daily basis.

The coming of the Barbarians in the peninsula didn’t only cause the end of the Roman Empire, but also that of such a tradition of, let us say, banqueting in style: this rugged-looking, harsh-speaking people from central and northern Europe had very little in common with Romans and their lifestyle.

As it always happens when cultures meet and clash, the two influenced each other, also in the kitchen: the Barbarians (who, as a matter of fact, ended up being the last straw needed to provoke the fatal collapse of the Empire, but who embraced with pure eagerness all that was Roman culturally, spiritually and socially) introduced the consumption of butter and beer, whereas the Romans passed on to them a taste for wine and olive oil.

History of Italian cuisine – the Middle Ages

Different was the culinary passage into the Middle Ages of Sicily which, since the 9 th century, had become an Arabic colony : islanders embraced the exotic habits and tastes of their colonizers, a fact mirrored also in their cuisine. Spices and dried fruit became a common concoction and are still often found in Sicilian dishes. Many may not know that dried pasta, today a quintessentially Italian thing, was brought to the country, specifically to Sicily, by the Arabs, who appreciated the fact it was easy to carry and preserve, hence perfect for long sea trips and sieges. From the ports of Sicily, dried pasta made its way to those of Naples and Genoa, as well as France and Spain. So, contrary to what we hear often when talking about the history of pasta , it wasn’t Marco Polo that brought noodles to Italian shores. This is how, we can truly say, an Italian legend was born.

It wasn’t only the influence of other populations to change and influence the Italian way of cooking and eating in the early centuries of the Middle Ages , but also that of religion. After Constantine declared Christianity a legal religion of the Empire and especially after it became the sole Imperial religion with the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, under the reign of emperor Theodosius I, Christianity began exercising heavy regulations upon people’s behaviors and habits , including the way they ate.

Food and eating were strongly associated with sin and with sexuality: pride, of course, was Adam and Eve’s sin, but it did manifest itself through the acts of a woman, who ate the forbidden fruit. As a consequence, spiritual perfection could be obtained through abstinence and fasting and, in particular, through renunciation to meat consumption.

Very much up to the year 1000, the monks of Italy (and of the whole of Europe, as a matter of fact) ate a strict diet of bread and legumes, with very spare additions of cheese and eggs on allowed days, along with some seasonal fruit . The meat was considered a dangerous aliment not only for its symbolic meaning: it was refused as food both because its production involved an act of blatant violence, the killing of an animal, but also because it was considered an energetic food, which could provoke in its consumer’s unclean desires and passions. In other words, Medieval Christians thought, meat could make you lose your chastity more easily than salad.

Roman banquets and the Barbarians’ habit to eat meat continuously on one side, Christian restrain of the other: the duality came to an end when Charlemagne managed to reconcile the two by declaring righteous an alternation of ascetic fasting with days of pleasurable feasting when even religious authorities and the faithful could give in to the pleasures of the table and consider it an offering to the greatness and goodness of God.

During these days of the feast, food became one and only with celebrating and honoring the Lord, just as fasting and restrictions did during the rest of the week. Monasteries slowly but steadily abandoned those strict ascetic regulations that had characterized them up to that point and opened to the flavors and tastes of good food on special occasions, which also became moments of prayer and reflection.

And what about castles and their inhabitants? What did they eat in the early Middle Ages? Let’s have a look into that side of the history of Italian cuisine!

Early middle ages as society

The social structure built around the castle and its lord had become, by the 11 th century, organized in an autarchic economical system which allowed most of its members (craftsmen, members of the military, servants, peasants) to eat regularly and with relative ease. The lord of the castle, of course, was the one with the fuller stomach, but even to him and his family, food was far from being a gastronomic matter: up to when living in the cities flourished again, in Italy before than everywhere else, and people’s mores became, once again, more refined, medieval banqueting remained closer to barbaric food feasts than to old, lavish and harmonious Roman banquets.

The later Middle Ages and the Renaissance

In the later Middle Ages, town life blossomed again with the development of the comuni culture: this supported the inception of early productive cores upon which a whole new social class was to found its roots: the bourgeoisie . Craftsmen were hit by higher demands, dictated by the higher number of people living in urban areas, as well as by a steep increase in commerce, both within and without the borders of Italy as we know it today.

The Crusades had opened up Europe to the idea of communicating with one’s neighbor and products began to circulate with much ease: a new social class, that of merchants was born. It is, then, among this crafts and commerce crowd that the pleasure of good food became, once again, a symbol of social and economic status . Cooking returned to be a matter of enjoyment and refinement, a voyage among flavors and combinations. Meats and vegetables were once again roasted and braised, the old art of stewing and dressing dishes in rich, flavorsome sauces was rediscovered.

The lords of the castle were going that extra mile to make things even more flamboyant, and embraced with flair the old imperial habit to present food and dishes on the plate spectacularly: birds were served decorated with their own feathers as if they were still living, pork was brought onto the table with its head still attached to the body, surrounded by pounds and pounds of sides.

Such a rediscovery of old, traditional ideas in the kitchen, coincided with the introduction of new culinary elements especially on the lords’ table: spices and cane sugar, introduced to Italy by the Arabs and grown in Sicily, substituted salt, pepper, or honey in many a dish and helped to create new flavors and recipes. It is, for instance, during the 13 th century that sugared almonds (called confetti in Italy) were created and usually served as a sign of culinary distinction at the end of very important dinners: of course, we’re talking about modern confetti, covered with a delicious sugar shell here, but the idea of having almonds or even aniseeds covered in a sweet shell was common already in Roman times. However, the Romans didn’t know sugar, so they would use a paste of honey and flour instead.

In general, almonds preparations became very popular, especially thanks to Sicilian cuisine and its love for Arabic flavors: it was in Sicily, for instance, that the Arabs introduced an ancestor of marzipan, which was to become a very popular medieval dessert. What many don’t know is that, very probably, the most famous of all Sicilian dessert , the cassata, may have Arabic origins, too. The cake, made with sheep ricotta mixed with sugar, sponge cake, royal paste (a sweet paste made of almond flour and sugar) and candied fruit, was created during the Arab domination of island, between the 9 th and the 11 th century.

Arabs had introduced sugar cane, lemons, and oranges to the cultures of Sicily and very soon they all became part of its cuisine: all these ingredients concurred, along with sheep ricotta, always produced in the South of Italy, and almonds, to create the cassata. Even its name may come from the Arabic word qas’at , which means “small basket,” and could indicate the container where the cake was made. However, other linguists think the name actually comes from the Latin caseum , which means “cheese.”

Either way, the roots of the dish itself are certainly Middle Eastern, even though it changed greatly throughout the centuries: for instance, the pasta di mandorle – a paste made with almond flour and sugar, which is an ingredient of marzipan – began to be used only during the Norman period to cover cassate . Before then, they were encased in shortbread.

Some place the origin of another delicious Italian sweet treat in the same period, and at the hand of the same people, the Arabs: it seems, in fact, that the history of gelato , the world famous Italian-style ice cream, is very much rooted on Sicilian soil and in Arabic culinary tradition. The Arabs commonly produced a sorbet-like concoction of sugar and fruit juices, turned into ice by keeping it immersed in a mixture of ice and salt.

They exported the method in Sicily, where fruits were plenty, marine salt local produce, and ice came easily from the peaks of Mount Etna . Even though gelato as we know it became a fixture of European tables only in the 1600s, thanks to the popularity it reached in France, Arabic Sicily wins the medal for having been the first place in the western world where its ancestor was produced.

The history of Italian cuisine and food is still long and fascinating. Get to learn more about what Italy inherited from the New World and the evolution of the Italian way of cooking up to modern times in the second part of our adventure in the history of Italian food .

History of Italian food part 2

History of Italian Food part 3

History of Italian food part 4

Related Posts:

Actually Etruscans already had pasta so…

Hi I always heard of “Amari” ( Bitter liqueur drink ) made by Monaci ( Monks ) and Frati but I will ask Francesca about Food recipes, she will know more than I do

Were there any medieval monks famous for cooking or cook books?

L’Italia e stata e sara’ sempre alla vanguardia della cultura. Viva L’Italia!

In response to Ventura who said (on Oct 2, 2019): “Italy is only 100 years old. How are you tracing Italian food back centuries.” The Italian NATION came into political existence approximately 150 years ago, after the wars of unification. BUT the italian culture is ancient, as are the foods, recipes and agriculture which produces the foods. I took three different university courses on italian food (NOT cooking, but history and culture). They had sophisticated cookbooks even in the 1400s and some still producing olive trees are 1,000 yrs old. So, Ventura, you can’t say that the political NATION determines how old a culture is, and that includes its foods.

The Roman legions grew wheat for their pasta……….long before Marco Polo. Catherine de Medici brought her chefs to France AND THAT IS WHEN THEY DISCOVERED HOW TO COOK! In Bath you can see the BATHS…….the Romans were CLEAN………and you can see the latrines they constructed of marble with a unique FLUSH of wast in Provence. FRANCE IS 100 YEARS OLD! HA HA.

Hello Rob, the tomato came later, with the discovery of America, as you mention. It’s on the second part of this article: https://www.lifeinitaly.com/history-of-food/the-history-of-italian-cuisine-ii

All that and not one mention of the tomato which is central in many dishes. They came from Mesoamerica after the Conquest. The word itself is Nahuatl, “tomatl”. What would Italian food be without the tomato?

Viva la Italiano!

Not true my friend the French have always been behind in Italian culture. Several years back the NYT had an article based on the power Italians have on fashion, food and the people themselves no comparison. The article gave credit to the French for their perfumy claiming they need it for their body oder. Italians have it all locked down oh did I mention looks also!!

Italy is only 100 years old. How are you tracing Italian food back centuries.

Thank God I was born in an italian family,the best food in the world. 🍷

The French taught the italiansvhow to make great food

Molto interessante. Very interesting. Thanks for sharing your knowledge. Looking forward to reading the other parts.

Grazie mille!

Recent Posts & News

Visiting Italy in April and May

April 25: Liberation Day

Travel in Italy for Single Women

Italy in May

After Easter… Pasquetta!

History of food.

In Italian Food, What's Authentic and Does It Really Even Matter?

Italians are passionate about their food culture, but the ingredients we eat and how we eat them are constantly evolving and changing over time.

I pride myself on having a profound understanding of what Italian food is and what makes it authentic. I know the difference between carciofi alla giudea , twice-fried artichokes in the style of the Roman ghetto, and carciofi alla romana , braised artichokes with garlic and mint in the style of Rome. I know that acqua cotta , one of the classics of Tuscan cooking, comes in at least three radically different versions depending on what part of Tuscany you are in. I know that even if an Italian would never sprinkle grated Parmigiano over his shellfish pasta, he would happily eat crostini with melted mozzarella and anchovies. I know that asparagus and tomatoes are not cooked together, because wherever you are on the boot they are not in season together. I know that long cooking of vegetables is a hallmark of Italian food wherever you are: no barely blanched green beans or asparagus for Italians, please!

I believe that my understanding of the flavor combination of fresh mozzarella, sun-ripened tomatoes, basil, and olive oil is a foundation that can steer me to many plates beyond the simple classic insalata Caprese I first ate, still sticky with salt from a morning in the water, at a beach-side restaurant in Capri. I laugh to myself at the many ridiculous combinations I come across outside of Italy, knowing that nobody with any understanding of Italian food would ever combine nettle-ricotta ravioli with puttanesca sauce.

And yet, I ask myself, what is authenticity and does it really matter? Italians are, of course, passionate about their food culture and ready at all times to chastise a foreigner for not understanding that right combinations or sequences of flavors. Salad always comes after the entrée -- never before. Pasta and soup fill the same slot in the meal, so you eat one or the other and not both. Plum tomatoes are for pasta sauce, globe tomatoes are for salad. And so it goes, a dizzying array of rules and regulations for how you eat. But still I wonder, what is the importance of authenticity?

Italian food and flavors changed dramatically after 1492 with the influx of the New World fruits and vegetables -- tomatoes, corn, beans, peppers, potatoes -- that were gradually integrated over four centuries of gardening and cooking and are at the core of today's version of Italian food. If we wanted to be really authentic with Italian food, shouldn't we do away with all the invasive species? Doesn't that make tomato sauce and polenta inauthentic?

Food is not static. What we eat is constantly evolving and changing. New things become available. When I was a child in Rome, cilantro, limes, and yams were unknown and unavailable; today, thanks to immigration and the global produce trade, you can probably find all three at the corner vegetable stand. When I first started paying attention to my neighbors' farm in Tuscany, they were extremely self-sufficient in terms of their food. They grew, raised, and foraged probably 90 percent of what they consumed. Their food and flavors were delicious and unvarying, and the dishes Mita cooked formed the basis of my understanding of Italian food.

And yet as the times changed and they began to watch television and shop for some food at the supermarket, variances drifted in. One year we had pasta with a canned truffle and cream sauce. Another Easter my mother was surprised by violets in the salad. "I saw it on TV," Mita said. Is it inauthentic to be inspired by new ingredients? Is it inauthentic to take the combination of insalata Caprese and manipulate the ingredients until they no longer resemble mozzarella, tomatoes, and basil but the flavor combination remains the same?

I cringe when Americans do strange things to classic Italian food: Spaghetti and meatballs has me running out the door with an excuse about my house burning down. Yet while I have never seen spaghetti and meatballs on a menu in Italy, I have seen plenty of fresh-off-the-boat Italian chefs appropriate the dish and add it to their repertoire.

Much as Italian food was changed by the discovery of the Americas and recently by immigration and a global market, Italian immigrants who came to America 100 years ago were influenced by the new ingredients and the lack of availability of ingredients that were common back home. Is it inauthentic to use Vietnamese fish sauce when we are pretty sure that 2,000 years ago the ancient Romans made and consumed fish sauce themselves?

As a chef who has tied my career to cooking "authentic" Italian food, who prides herself on knowledge of what is proper Italian and what is not, I have been amazed and intrigued at what Italians make their own. Years ago in Puglia I ate in a little tiny restaurant that prided itself on everything coming from the garden out back or the farm down the road. The different cheeses we ate were described as yesterday's cheese and last month's cheese. But when I went back the next day to cook with them, I was amazed to find them happily using Kraft singles in their eggplant Parmesan. I thought I had misheard or misseen, but no, they really were using Kraft singles without any sense of destroying the authenticity of their food.

Recently, I had an Italian chef in my kitchen who requested Worcestershire and Tabasco to put in her tomato sauce. Is that inauthentic? Or is it simply adapting in the same way that people adapted new products like corn to their traditional dishes of grain gruel made with millet, barley, or farro? Do I really care if someone sprinkles mint over fried artichokes? It actually sounds good. I have found the combination of soy sauce and extra virgin olive oil to be delicious. Is that a bad thing? It's certainly inauthentic right now, but will it be considered a standard element in Italian cuisine 50 years from now?

I think that as a non-native Italian it has been tremendously important to me to define my understanding of the cuisine as an understanding of the traditions that go into the food. It becomes terrifically important to be able to say "I might not have an Italian name or been born in Italy, but my ability to know and cook what is authentic means I am just as Italian as Luciano Pavarotti." I do believe that often there is a reason behind many of the dishes we love and cherish and revere as authentic to us. And I do believe you have to really understand the classics in anything to start rearranging them. But food is not static, and our tastes are not static. And perhaps if I was Italian to the bone I would feel freer to add Worcestershire sauce to my tomato sauce. Maybe I would roast sweet potatoes with rosemary and garlic and not think twice about it.

When I taste traditional French food with its flour-thickened, rich, long-cooked sauces, I don't enjoy it. It tastes old and stale and boring. I don't agree that innovation for the sake of innovation is necessarily a good thing, and I don't enjoy molecular gastronomy necessarily any more than I do classic haute cuisine French food of the 1950s. But for me a truly confident chef is able and eager to appropriate new ingredients and techniques. Things change, our palates change and what was new today may become the tradition of tomorrow -- a tradition so ensconced that the minute you think of that cuisine you think of the dish, the way pasta with New World tomato sauce or New World polenta immediately makes you think of Italy.

Image: Petrafler/ Shutterstock .

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — National Cuisine — The History of Italian Cuisine: Delicacies and Traditions

The History of Italian Cuisine: Delicacies and Traditions

- Categories: National Cuisine Table Manners

About this sample

Words: 1275 |

Published: Aug 1, 2022

Words: 1275 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 371 words

2 pages / 850 words

1 pages / 554 words

4 pages / 1716 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on National Cuisine

Food and culture share an intimate and intricate relationship, weaving together the flavors, traditions, and stories that define societies across the globe. This essay embarks on a journey to explore the profound connection [...]

Food is a universal language that unites cultures and brings people together. However, not all foods are created equal, and some dishes are subject to misconceptions and misunderstandings. One such dish is mofongo, a traditional [...]

Floribbean cuisine, also known as “new era cuisine”, has emerged as one of America’s new and most innovative regional cooking styles. Floribbean cuisine is representative of the variety and quality of foods indigenous to Florida [...]

According to Oxford dictionary, the definition of culture is the art and manifestations such as humanities, literature, music and painting of human intellectual acquirement considered common. It is also set of learned [...]

Thai cuisine is world famous cuisine or food. Thai cuisine is basically from southeastern Asia and national cuisine of Thailand. Thai food is generally for its spiciness and tantalizing tastes. Thai food as demonstrating [...]

With the increase in willingness to experiment with their flavors on the plate, an increasing number of people are willing to try ethnic food of various other cuisines which would help them get a feel of the place that cuisine [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Culture of Italian Food Essay Example

The culture of Italian food stretches back to the origins of the Roman Empire. The majority of their ingredients came from a land far away which they have conquered. A predominantly Mediterranean diet was the main food consumed. By the first century, chronicles began preserving Roman recipes of what was being eaten and how they were prepared. This ushered in the new period known as the Middle Ages, where new groups of people took charge and brought with them different types of spices, fruits, methods of cooking, and diets based on following their religion. It was during the Renaissance rebirth that a multitude of foods from all over the world was imported into Italy. Italian cuisine evolved using these new ingredients, creating both new and changing old recipes as they found their way into various regions. Eventually, the food shared as recipes, at festivals, with friends and relatives, became part of the rest of the world. Now, one can discover and try a taste, an exotic variation of distinctive flavors.

The importance of food was vital to life as well as its respect in all ways. Health was a concern of the people who chose to stick to a Mediterranean diet. This is a diet that contains vegetables, spices, olive oil, herbs, and others, which gives nourishment to the body during holidays like Saint Day and on an everyday basis. In contrast, for other holidays like Christmas, families tend to eat light since on Christmast they eat heavy foods such as pasta, meat, etc. others. It is usually mom who cooks in Italian culture since she takes great pride in her food, using ingredients from ancestors or making sure to use the freshest vegetables and herbs in a particular area, making the food taste particularly good. The things mom used were pasta, meat, olive oil, and sauce. Several-course meals are traditionally shared with the family since dried vegetables and cheese are both consumed. They would then have pasta and cheese before continuing with meat or seafood, such as fish, and then drink coffee and wine. Another important part of culture is lunchtime. During lunchtime, people can spend an hour eating at home. By cooking at home, it allows people to have a healthier diet because they're providing the family with healthy options. In this culture, people experience less unemployment as food provides energy, so they stay healthy and are more productive at work.

The country is full of flavors, tastes, and the quality of the different regions. Different varieties of food are seen to be eaten in each region because of access and what grows. Due to the climate, the soil, and the ingredients grown in the place, each region has a different blend of ingredients, and the locals would be required to incorporate their traditions into new recipes that combine fresh ingredients to make something delicious. A great variety of herbs and spices are used in all regions of the world, and there is a great deal of fish in the dishes. Typically, Italians cook simple dishes well known to their country, which is important because they're looking to capture the taste and all the flavors of a few quality ingredients to make a great meal. Food is their passion, as everything becomes simple when they cook. The effort and time to create something beautiful with lots of colors are evident in their cooking. Along with the food being cooked for a short time, a good meal can also be enjoyed for a few hours between breaks when families gather to share their experiences and reconnect with old memories. Ingredients can be an important part of Italian cultures such as olive oil, pasta, and wine. Olive oil was considered a source used to substitute fat from animals or even butter because it was considered healthier than a Mediterranean diet used in sauces, pasta, meat, and seafood. Pasta is considered a separate course usually eaten with just sauce. Considered an important part of the culture which is shared throughout Italy which was influenced by a product brought back by Marco Polo which was soon slowly eaten made out of durum wheat. This food comes in lots of varieties where each region eats pasta in its own style where people love to enjoy it slowly because of all the different tastes and flavors combined.

It is said that the Italian and American food cultures are very different because the Italian food culture is about sharing simple ingredients with family and friends while the American food culture is about comfort foods that are not healthy. Fresh ingredients in season and those that are local to the region are what Italians eat because they tend to have more flavor and are tastier. Freshly grown fruits and vegetables are sold at farmer markets. Breakfast is considered to be a light meal similar to a snack. During lunch and dinner, they eat multiple courses and eat them in small portions so that they can digest everything properly. The weekends are a time for eating at home with others and interacting where few people go out. The food in America is also influenced by the cultures of the different countries and the territories they once occupied. A quarter of the people eat fast food each day here. People here enjoy fast food. American cheeses, meats, and sugar are the major foods consumed by Americans. As convenient as eating out at restaurants, ready-made food is just as convenient, considering nobody enjoys cooking since it takes a lot of time and would be very difficult given that they're classless and never learned to cook from their parents. Assuming individuals are paying for a meal, they want larger portions As for other countries, foods can be expensive so taking the family out to eat will cost more than they expected. This is similar to how 90 percent of Italians eat at home on Sunday. Americans dislike breakfast most because it is a time-consuming meal, and they are always busy doing other things so they take out time to eat. During lunch, people are rushed because there is little time to eat, so they usually eat sandwiches and salads, and whatever they don't finish gets thrown away because they don't have time and the price is cheap so nobody wastes anything. It is not uncommon for many families to not have a good relationship where no one communicates with each other at dinner time. As seen health is never questioned when taking good care of yourself because the cost will be too much to worry about making the best choice of what to put in your body as others feel they have been doing what is right all the time without knowing the bad stuff.

The Italian food culture has always stuck to the true quality of simplicity using what you got with a few requirements to make a meal. Different cultures' influences on the Italian food has made the food eaten very unique with different dishes in each region all using local products to create their own traditional meals. These can be shared at festivals or with family to create memories with those who like good food as others.

Related Samples

- The Removal Act of 1830. Essay on Genocide Against native Americans

- Traditional Grading System in America Free Essay Sample

- Iranian Hostage Crisis Essay Example

- Three Theories on How the Pyramids Were Made: Ancient Egypt Essay Example

- What it Means to Live in Cuba Essay Example

- Essay on Ancient Greeks Inventions: The Impact on Modern Day Society

- Essay Sample about Sweetened Beverages

- Essay on Algonquin Tribe

- 50s and 60s: The Time of Great American Technological Innovations Essay Example

- Kite Runner Essay Sample

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

How Italy blends culture with cuisine - a photo essay

Photographer Harriet Zawedde was born in Rome but raised in the UK. Her series Nightshade, combines portraits with botanical images of the tomato plant and the subjects’ recipes

T he English word tomato derives from the Aztec word tomatl . It is believed the Aztecs and Incas were cultivating and eating the tomato from 700AD. Though the tomato originated from the Andean region, it eventually spread north to Mexico. The scientific name for the tomato is solanum lycoperscicum .

While the Spanish were responsible for bringing the tomato to Europe in the early 16th century, its first reference in Italy was in 1544 in Pietro Andrea Mattioli’s Herbal, who refers to the tomato as pomi d’oro meaning golden apple. The tomato was not used in cooking until the 18th century as it was often viewed with fear and suspicion as a member of the nightshade plant family, which had plants such as the mandrake among them.

Once the names the tomato were called were amended and confusion and ambiguity as to what it was subsided, it was able to illustrate its full potential. After its family ties became less relevant and it was allowed to exist for what it was, not how it looked, it thrived. This took an element of trust.

Below, Nightshade’s subjects discuss their favourite recipes.

I can tell you, lasagna is the first dish I learned to cook. I moved out from my parents’ house without knowing how to cook even a common pasta but since lasagna and pollo con patate, are my favourite dishes, I learned how to cook them first. Even though making the ragu isn’t so easy. I tried my best and my lasagna is one of the best in town, if you get in Brianza by any chance, you’ve got to taste it.

Evelyne’s lasagna Ingredients: Egg lasagna | Passata | Celery | Carrots | Onions | Mince | Parmesan | Olive oil | Homemade béchamel | Salt | Pepper | Basil Fry the onion until softened. Add the carrot and cook for five minutes, then add the celery and cook for another two minutes. Turn up the heat, add the chopped beef and cook until browned all over. Make a ragu over an afternoon, pour in the wine and passata, season with salt, pepper and a pinch of grated nutmeg, then bring to a simmer. Make your own béchamel. Place cooked ragu into an overproof dish and layer. Top with parmesan. Garnish with basil.

This is a classic Italian recipe. If you ever jump on a plane to Italy , don’t miss it.

Since I was a child, this has been my favourite recipe. I remember cooking it for every family party, even for my sister’s wedding. With this recipe you will never go too far wrong. Your guests will love Crostata. This recipe is a mix of authentic Italian flavours, in which lemon and marmellata (jam) are the main ingredients for a unique and refined taste.

Good luck and enjoy!

Claudia’s crostata alla marmellata Ingredients: 250g cold butter from the fridge | 200g of icing sugar | 500g of 00 flour | 2 eggs | The rind of an untreated lemon | 400g of jam | Enough milk to brush the surface | A pinch of salt Put the flour, butter and a pinch of salt in the mixer. Mix in order to obtain an uneven sandblasting. Add the eggs, icing sugar and lemon peel to flavour the pastry and allow the citric acid to make it crumbly. Knead the dough before putting it onto a work surface. Start working it with the fingertips, to create a nice compact dough. Wrap it in clingfilm and let it rest for 30 minutes in the fridge, or ideally overnight. After letting the dough rest, we heat it and flatten it. Aim for a thickness of 7/8mm. Transfer the dough into a 24cm diameter cake pan and pinch the bottom with a fork. Then we make our short pastry with jam, we distribute it on the edge. After that, prepare 3 or 4cm strips of dough and place on to the jam, applying pressure to the edges. Lay the strips diagonally creating a grid of pastry and diamond shapes of jam. To make the tart shiny, brush the milk on the pastry with a pastry brush. After that, we bake the tart in a pre-heated oven at 170C for 50 minutes.

Fiorentina is one of the most popular and biggest steak in Italian cuisine.

I have eaten this more than three times and its taste was undeniable. I think it is one of the best dishes that I often have because it reminds me of Tuscany’s fabulous and iconic lifestyle.

Simon’s fiorentina

Ingredients: T-bone steak | Salt | Pepper (coal fire) Use the highest quality steak, ideally Tuscan or Italian. Cook on an open fire if possible (on the embers of the grill). Rare or medium rare only. Garnish with salt and pepper.

Pizza has always been a reason to gather with my friends. Pizzerias were fancy enough for our student pockets. When my mum would make pizza at home, we were always very excited.

For me, it was nice to see the first generation of immigrants learning the Italian cooking as their way of integration.

Abigail’s pizza al prosciutto e funghi Ingredients: Semolina pizza dough | tablespoon olive oil | 2 cloves chopped garlic | 5 mushrooms thinly sliced | mozzarella cheese | 1 can tomatoes | chopped roma | 1 bell pepper| thinly sliced prosciutto | salt & pepper to taste | oregano | pepper flakes Preheat oven to its hottest setting for 45 minutes. With about 1 teaspoon olive oil, sauté the sliced mushrooms and a pinch of salt over medium heat for 5-10 minutes, until well browned. Set aside. Sprinkle semolina on your baking sheet. Place the dough on top of the semolina and roll out into a circular shape. Brush the outer edges with olive oil and chopped garlic. Spread chopped tomatoes from the centre out to the edge of the oiled crust. Evenly place your toppings (mushrooms, mozzarella, bell pepper, etc) on the dough. Sprinkle with salt, Italian seasoning and pepper flakes, to taste. Add Parmesan cheese if desired. Transfer the pizza onto your stone by sliding it off the baking sheet. Bake for 10+ minutes, or until the crust is nicely browned and the cheese is bubbly. Remove with tongs and let rest for five minutes.

I usually cook it during summer for lunch, after a long morning at the beach. It is easy, quick and everyone loves it, including my kids. The pepper is not that hot. It is a plate that I particularly love because I buy the shrimps fresh from the local fish store near the beach.

Nadege’s pasta con gamberoni, peperoncino e pangrattato Ingredients: Shrimps from Marsala Tomatoes from pachino | 300g spaghetti | Olive oil | Garlic | Hot pepper | Salt In a frying pan add some oil, garlic and hot pepper then mix all together until the mixture becomes a little golden. In the meantime, boil some water for the pasta. Add two or three tablespoons of the boiling water into the mixture. Then let it sit for a couple of minutes until the pasta is cooked. Add salt and pepper. Mix everything together.

Aubergines are my all-time favourite late summer/winter vegetable. This dish reminds me of childhood, having a family meal at a local tavola calda. It can be eaten as a standalone dish or as part of a secondo piatto. It’s one of the most unassuming yet deliciously hearty dishes. I’ve probably adulterated the dish to suit my palette but this is a firm favourite for me to prepare for my nearest and dearest. If you want a leaner version of this dish, try grilling the aubergines instead. An exceptionally tasty vegetarian treat.

Tiwonge’s melanzane alla parmigiana Ingredients: 3 large aubergines | 1 bottle of tomato passata | 2 cloves of garlic 2 balls of mozzarella | 1 cup of parmigiano reggiano (grated) | 1 cup of extra virgin olive oil | 1 cup flour | 1 cup vegetable oil | Black pepper to taste | Fresh basil to taste | Salt to taste Preheat oven to 180C (356F). Slice aubergines lengthways but leave skin on. Place in a bowl and sprinkle two tablespoons of salt over them and leave for an hour to remove the moisture. In the meantime prepare the sauce. Add two teaspoons of olive oil to a pan and finely chop garlic cloves. Fry until softened. Add passata and cook on medium heat on hob for 15 minutes. Tear and add fresh basil and black pepper and salt. Cook for a further 10 minutes. Chop mozzarella into small cubes. Place flour into a bowl. Take aubergines out of salt and coat each in the flour. Prepare a new pan with two tablespoons vegetable oil and fry off flour coated aubergines- about 1-2 minutes each side. Place on kitchen towel to absorb oil. Add more cooking oil to pan if required.Prepare an oven baking dish. Start by spoon- ing some of the passata onto the base. Then place a layer of aubergines on top, add some passata, parmesan and mozzarella. Repeat until all ingredients have been used. Bake for 25-30 minutes. Serve with a sprig of basil and enjoy this heart-warming beautiful dish.

This is a classic Italian antipasto. It is the perfect dish for when you invite your friend for dinner because it is easy to make and very tasty.

Bintou’s caprese Ingredients: Mozzarella | Tomato | Extra virgin olive oil | Oregano | Salt | Pepper Slice mozzarella and tomato and place on plate. Apply a generous amount of extra virgin olive oil. Season with salt, pepper and fresh oregano.

This dish reminds me of the long summers in my childhood, and I used to enjoy this on a picnic or by the beach. It brings memories of laughs, sun, water, running barefoot in the hot sand, beach games and the joy of eating all together.

Cinzia’s pomodori di riso alla romana Ingredients: 4-5 medium firm ripe round tomatoes seeded and hollowed out | 1 cup uncooked rice (I used long grain par boiled) 185 grams | 1 teaspoon oregano 1/2 gram | 1 teaspoon basil 1/2 gram | 1/2 teaspoon salt 2 1/2 grams | 1/2 gram *6 springs fresh chopped Italian parsley | 1 clove garlic chopped | 1/4 - 1/2 cup chopped tomato pulp 55-82 grams | 2-3 tablespoons olive oil Pre-heat oven to 180C (375F) and lightly oil a large baking pan. In a medium bowl add rice and cover with water, allowing it soak for one hour, then drain and rinse. Rinse and dry tomatoes, carefully cut off top of tomato and set aside. Remove seed and pulp from the tomatoes, set aside the pulp and discard the seeds. In a medium bowl mix chopped tomato pulp, oregano, salt, parsley, garlic, 2-3 tablespoons (45 grams) olive oil and rice. Fill hollowed out tomatoes with mixture. Place tops back on tomatoes, sprinkle tomatoes with a little salt and drizzle with olive oil. Add roasted potatoes with rosemary and bake for approximately 45- 60 minutes or until potatoes and rice are tender. Serve immediately. Enjoy.

This is my favourite dish for three reasons: though based on rather basic ingredients, it is unabashedly rich and indulgent; its reddish/orangey colours evoke those of my favourite team (AS Roma), and you can do an excellent version of it in under 30 minutes.

Joseph’s amatriciana

Ingredients: Guanciale (cured Italian pig cheek. Do not use pancetta in any circumstance) | Pecorino Romano (abundant) | Tomato passata Calabrian chili | Salt | Pepper | Rigatoni or bucatini | Wine Dice the guanciale into thin strips. Remember to remove the hard part of the skin, and to slice off a bit of fat if the ratio of meat to fat is less than 1:3. Add to a non-stick pan at medium heat and let it heat gently until the guanciale is crispy and the fat renders. Add a splash of dry white wine (like a frascati), to deglaze the pan. This step is optional. Once the alcohol has evaporated, add some flakes of chilli and a high-quality tomato passata (or blended chopped tomatoes). Add some seasoning (but not too much salt), and let it simmer on a medium heat. In the meantime, bring water to the boil, and add either rigatoni (short pasta) or bucatini, depending on your (and guests’) preference. Tip: growing up I was always told that the water of the pasta must be as salty as the Mediterranean. Few things are more upsetting than an under-salted pasta. So be generous when salting the boiling water for pasta. Two minutes before the pasta is ready, set aside some of the starchy boiling water, and then quickly decant and add to the sauce. Another tip: always toss pasta into sauce, not vice versa. The pasta is at its most absorbent in the 10 seconds after it has been drained, so don’t waste time in mixing it with the sauce. As you toss it in, add in generous heaps of grated pecorino cheese, which should gently melt. This renders the sauce less red but also thicker. Use the water set aside to regulate the consistency. A good amatriciana must have a touch of sleepiness to it. Plate - on a heated plate preferably, add some grated pecorino and buon appetito .

www.harrietfairbairn.com | @harrietoflondon

- The Guardian picture essay

- Italian food and drink

Italian academic cooks up controversy with claim carbonara is US dish

Tomato-free pizza on UK menus as chefs choke on the price of fruit and veg

The secret behind Britain’s top pasta chef’s winning dish? It’s gluten free and vegan

A local’s guide to Parma, Italy: city of cheese, ham and stunning baroque buildings

Italian researchers find new recipe to extend life of fresh pasta by a month

There’s more to spritz than Aperol

'Stop this madness': NYT angers Italians with 'smoky tomato carbonara' recipe

Italian or British? Writer solves riddle of spaghetti bolognese

Most viewed.

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Food and Language

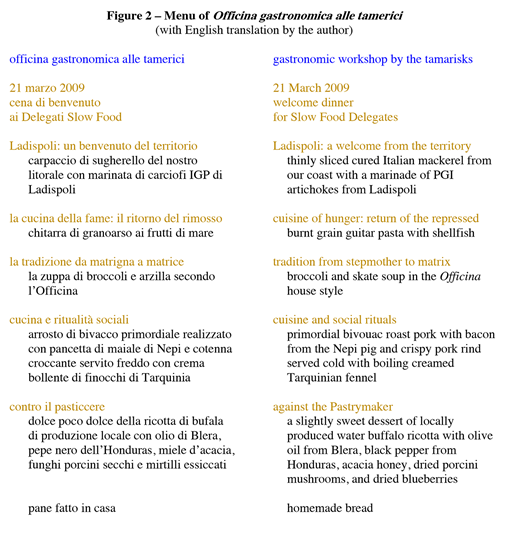

Language of food activism in italy, slow food restaurant menu and dinner at officina gastronomica alle tamerici, conclusion: language and food activism, acknowledgments, food activism and language in a slow food italy restaurant menu.

Carole Counihan is professor emerita of anthropology at Millersville University and has been studying food, gender, culture, and activism in Italy and the United States for forty years. She has published several book chapters and journal articles and the following books: Italian Food Activism in Urban Sardinia (Bloomsbury 2019; Italian edition Rosenberg and Sellier 2020), A Tortilla Is Like Life: Food and Culture in the San Luis Valley of Colorado (Texas University Press 2009), Around the Tuscan Table: Food, Family and Gender in Twentieth-Century Florence (Routledge 2004), and The Anthropology of Food and Body (Routledge 1999). She is the co-editor of Food and Culture: A Reader (Routledge 1997, 2008, 2013, 2018), Taking Food Public (Routledge 2012), Food Activism (Bloomsbury 2014), and Making Taste Public: Ethnographies of Food and the Senses (Bloomsbury 2018). She is editor-in-chief of the scholarly journal Food and Foodways .

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

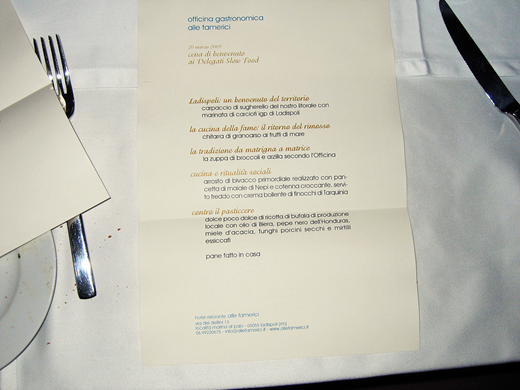

Carole Counihan; Food Activism and Language in a Slow Food Italy Restaurant Menu. Gastronomica 1 November 2021; 21 (4): 76–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2021.21.4.76

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

This essay explores how food activists in Italy purposely shape food and language to construct meaning and value. It is grounded in years of ethnographic fieldwork on food and culture in Italy and looks specifically at the Slow Food Movement. The essay explores language and food activism through a detailed unpacking of the text of a menu prepared for a restaurant dinner for delegates to the Slow Food National Chapter Assembly in 2009. The menu uses descriptive poetic language to construct an idealized folk cuisine steeped in local products, poverty, history, and peasant culinary traditions. As I explore the language of the menu and the messages communicated by the food, I ask if they intensify people’s activism, advance Slow Food’s goals of “good, clean and fair food,” and promote food democracy.

Food activists in Italy mutually shape food and language in the construction of meaning and value. Food and language intertwine in many ways and pointed language can shape new understandings of cuisine and culture. This essay uses the Italian Slow Food Movement as an example of food activism and considers its goals and tactics, particularly as they are conveyed through alimentary language. Food activism consists of “people’s efforts to promote social and economic justice by transforming food habits” ( Counihan 2019 : 1) and includes buying organic and Fairtrade products, frequenting farmers markets, establishing community gardens, organizing against pesticides or GMOs, maintaining quality product designations, supporting legislation, and so on. Overall, it pursues food democracy: “the vision of an ecologically sound, economically viable, and socially just system of food and agriculture” ( Hassanein 2003 : 84).

The essay examines the kind of food activism Slow Food promotes by performing a detailed exegesis of the menu of a restaurant dinner for delegates to the Slow Food National Chapter Assembly in 2009. It considers food not only as discourse created through the language of the menu but also as material substance on the plate, analyzing its symbolism in the context of Italian history and culture. The essay asks if the alimentary language of one menu in particular, and of food activism in general, can help produce the counter-hegemonic attitudes and behaviors fundamental to food system change.

Analysis of the menu reveals its construction of an idealized folk cuisine based on local, humble, tasty dishes grounded in historically important places and traditions. 1 Folk cuisine is similar to what pioneering folklorist Don Yoder called “folk cookery…traditional domestic cookery marked by regional variation” ( 2015 : 21). It includes “the foods themselves, their morphology, their preparation, their preservation, their social and psychological functions, and their ramifications into all other aspects of folk-culture.” For Italians, folk cuisine is cucina popolare , “popular cuisine, cuisine of the people,” or cucina povera , “humble cuisine, cuisine of poverty” ( Montanari 2001 ). 2 In Italy, folk cuisine has historically been rooted in the countryside and the peasant families who comprised the majority of the population for most of Italian history. Today folk cuisine is an idealized construct rather than daily fare. Since the 1930s, Italians have steadily abandoned peasant farming, and the percentage of the population employed in agriculture dropped from 47 percent in 1930 to 4 percent in 2008, where it remains today ( Pratt and Luetchford 2013 : 27). Since the 1980s, Italians have increasingly consumed processed, imported, and mass-produced foods in place of the locally raised foods of the past ( Vercelloni 2001 ).

The folk cuisine depicted in the Slow Food dinner menu accentuated three threads. First, it was local food, rooted in place, with the implication that locality was crucial to (although not synonymous with) quality and environmental sustainability. Second, folk cuisine was steeped in history and tradition, which generated pride but also a potential undercurrent of xenophobia. Third, it was a cuisine of poverty, born from scarcity, hunger, and inexpensive foods, which raised issues of access and equity. As I explore the language of the Slow Food dinner menu and the messages communicated by the food, I ask what kind of activism they promote and whether they advance Slow Food’s overriding goals of “good, clean and fair food”—“good: quality, flavorsome and healthy food; clean: production that does not harm the environment; fair: accessible prices for consumers and fair conditions and pay for producers.” 3

Founded in Italy in 1986, Slow Food is a global association claiming a million supporters and 100,000 dues-paying members in 160 countries organized into roughly 1,500 local chapters called “convivia” worldwide and condotte in Italy. 4 The association is an important player in Italy’s landscape of food activism, taking place alongside of and sometimes participating in other initiatives including community or school gardens, solidarity purchase groups, farmers markets, Fairtrade, farmworker organizing, and so on. Slow Food has grown beyond its early focus on good food to “becoming a legitimate actor in the political arenas of food production and consumption…climate change…energy and biodiversity” ( Siniscalchi 2018 : 186). Some adherents, such as twenty-six-year-old Riccardo Astolfi from Bologna, described its evolution from the “old soul” ( vecchia anima) to the “new soul” ( nuova anima ): “When I say the old soul, I refer to people who get together exclusively for hedonistic pleasure, for gourmet food for rich people. The new soul was born on the road to Terra Madre and is summarized…in the triad ‘good, clean and fair.’” Terra Madre is the biannual meeting Slow Food has held since 2004 for producers, consumers, chefs, and activists from all over the world, and within the association it represents the shift toward “eco-gastronomy” linking good food to environmentalism and labor justice. 5 The evolution from the old soul to the new soul has not been without conflicts and tensions, which members told me have often played out in the condotte .