A systematic literature review of risks in Islamic banking system: research agenda and future research directions

- Original Article

- Published: 20 December 2023

- Volume 26 , article number 3 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- M. Kabir Hassan 1 ,

- Md Nurul Islam Sohel 2 ,

- Tonmoy Choudhury 3 &

- Mamunur Rashid ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6688-5740 4

116 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This study employs a systematic review approach to examine the existing body of literature on risk management in Islamic banking. The focus of this work is to analyze published manuscripts to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research in this field. After conducting an extensive examination of eighty articles classified as Q1 and Q2, we have identified six prominent risk themes. These themes include stability and resilience, risk-taking behavior, credit risk, Shariah non-compliance risk, liquidity risk, and other pertinent concerns that span various disciplines. The assessment yielded four key themes pertaining to the risk management of the Islamic banking system, namely prudential regulation, environment and sustainability, cybersecurity, and risk-taking behavior. Two risk frameworks were provided based on the identified themes. The microframework encompasses internal and external risk elements that influence the bank's basic activities and risk feedback system. The macro-framework encompasses several elements that influence the risk management environment for Islamic banks (IB), including exogenous institutional factors, domestic endogenous factors, and global endogenous factors. Thematic discoveries are incorporated to identify potential avenues for future research and policy consequences.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Based on Brocke et al. ( 2009 )

Modified from Al Rahahleh et al. ( 2019 )

Similar content being viewed by others

Risk Management Methodologies: An Empirical Macro-prudential Approach for a Resilient Regulatory Framework for the Islamic Finance Industry

Risk Management and Banking Business in Europe

What are the possible future research directions for bank’s credit risk assessment research a systematic review of literature, data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Riba has been at the center of mainstream debate categorizing Islamic finance from its counterpart. While many scholars identify Riba is the excessive amount of additional payment charged or given on the principal amount, for others it is the fixed or predetermined amount of payment on the top of the principal amount. However, the consensus among Islamic scholars forwards the notion that Riba in any form is prohibited in Islam.

Mudarabah is a partnership-based Islamic finance contract between two parties, one party supplying the finance ( rabbulmal ), while the other party gets involved with their physical labor and skills ( mudarib ), granting each party a share of the income at predetermined ratio.

Musharakah is another classical partnership contract in Islamic banking where more than one party contributes in financing a shared company. The contract involves both parties agreeing on sharing profit on an agreed-upon ratio and sharing losses on ratio of equity capital financed.

Operational risk is the potential loss due to inefficient internal processing, system and people, and external factors such as the limited legal support and uncontrollable compliance issues (Čihák & Hesse 2010 ).

AAOIFI. (2010). Governance standards for Islamic financial institutions. In. Bahrain: Accounting and auditing organization for Islamic Financial Institutions

Abdul-Rahman, A., A.A. Sulaiman, and N.L.H.M. Said. 2018. Does financing structure affects bank liquidity risk? Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 52: 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2017.04.004 .

Article Google Scholar

Abedifar, P., P. Giudici, and S.Q. Hashem. 2017. Heterogeneous market structure and systemic risk: Evidence from dual banking systems. Journal of Financial Stability 33: 96–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2017.11.002 .

Abedifar, P., P. Molyneux, and A. Tarazi. 2013. Risk in Islamic Banking. Review of Finance 17 (6): 2035–2096. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfs041 .

Aggarwal, R.K., and T. Yousef. 2000. Islamic banks and investment financing. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 32 (1): 93–120.

Ahmad, A.U.F., M. Rashid, and A. Shahed. 2014. Perception of bankers and customers towards deposit and investment mechanisms of islāmic and conventional Banking: Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Islamic Business and Management 219 (2622): 1–24.

Google Scholar

Akin, T., Z. Iqbal, and A. Mirakhor. 2016. The composite risk-sharing finance index: Implications for Islamic finance. Review of Financial Economics 31: 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rfe.2016.06.001 .

Al-Shboul, M., A. Maghyereh, A. Hassan, and P. Molyneux. 2020. Political risk and bank stability in the Middle East and North Africa region. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 60: 101291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2020.101291 .

Al Rahahleh, N., M.I. Bhatti, and F.N. Misman. 2019. Developments in risk management in Islamic finance: A review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12 (1): 37–58. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12010037 .

Alaabed, A., M. Masih, and A. Mirakhor. 2016. Investigating risk shifting in Islamic banks in the dual banking systems of OIC member countries: An application of two-step dynamic GMM. Risk Management 18 (4): 236–263. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41283-016-0007-3 .

Alam, N., B.A. Hamid, and D.T. Tan. 2019. Does competition make banks riskier in dual banking system? Borsa Istanbul Review 19: S34–S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2018.09.002 .

Alandejani, M., and M. Asutay. 2017. Nonperforming loans in the GCC banking sectors: Does the Islamic finance matter? Research in International Business and Finance 42: 832–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.07.020 .

Alhammadi, S., S. Archer, and M. Asutay. 2020. Risk management and corporate governance failures in Islamic banks: A case study. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 11 (9): 1921–1939.

Ali, M., and C.H. Puah. 2018. Does bank size and funding risk effect banks’ stability? A lesson from Pakistan. Global Business Review 19 (5): 1166–1186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150918788745 .

Ali, S.S., N.S. Shirazi, and M.S. Nabi. 2013. The role of Islamic finance in the development of the IDB member countries: A case study of the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan. Islamic Economic Studies 130 (905): 1–10.

Anwer, Z. 2020. Salam for import operations: Mitigating commodity macro risk. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 11 (8): 1497–1514. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-09-2018-0142 .

Ariffin, N.M., S. Archer, and R.A.A. Karim. 2009. Risks in Islamic banks: Evidence from empirical research. Journal of Banking Regulation 10: 153–163.

Archer, S., and R.A.A. Karim. 2009. Profit-sharing investment accounts in Islamic banks: Regulatory problems and possible solutions. Journal of Banking Regulation 10 (4): 300–306.

Archer, S., R.A.A. Karim, and V. Sundararajan. 2010. Supervisory, regulatory, and capital adequacy implications of profit-sharing investment accounts in Islamic finance. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 1 (1): 10–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/17590811011033389 .

Asutay, M. 2007. Conceptualisation of the second best solution in overcoming the social failure of Islamic finance: Examining the overpowering of homoislamicus by homoeconomicus. IIUM Journal in Economics and Management 15 (2): 167–195.

Asutay, M. 2012. Conceptualising and locating the social failure of Islamic finance: Aspirations of Islamic moral economy vs the realities of Islamic finance. Asian and African Area Studies 11 (2): 93–113.

Aysan, A.F., and M. Disli. 2019. Small business lending and credit risk: Granger causality evidence. Economic Modelling 83: 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.02.014 .

Baele, L., M. Farooq, and S. Ongena. 2014. Of religion and redemption: Evidence from default on Islamic loans. Journal of Banking & Finance 44: 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.03.005 .

Baker, M.J. 2000. Writing a literature review. The Marketing Review 1 (2): 219–247.

Basher, S.A., L.M. Kessler, and M.K. Munkin. 2017. Bank capital and portfolio risk among Islamic banks. Review of Financial Economics 34: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rfe.2017.03.004 .

Basiruddin, R., and H. Ahmed. 2019. Corporate governance and Shariah non-compliant risk in Islamic banks: Evidence from Southeast Asia. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 20 (2): 240–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-05-2019-0138 .

BCBS. (2001). Customer Due Diligence for Banks. Switzerland: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.

Belkhir, M., J. Grira, M.K. Hassan, and I. Soumaré. 2019. Islamic banks and political risk: International evidence. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 74: 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2018.04.006 .

Bitar, M., M.K. Hassan, and T. Walker. 2017. Political systems and the financial soundness of Islamic banks. Journal of Financial Stability 31: 18–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2017.06.002 .

Berger, A.N., N. Boubakri, O. Guedhami, and X. Li. 2019. Liquidity creation performance and financial stability consequences of Islamic banking: Evidence from a multinational study. Journal of Financial Stability 44: 100692.

Boukhatem, J., and M. Djelassi. 2020. Liquidity risk in the Saudi banking system: Is there any Islamic banking specificity? The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 77: 206–219.

Bouslama, G., and Y. Lahrichi. 2017. Uncertainty and risk management from Islamic perspective. Research in International Business and Finance 39: 718–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2015.11.018 .

Brocke, J. V., Simons, A., Niehaves, B., Niehaves, B., Reimer, K., Plattfaut, R., & Cleven, A. (2009). Reconstructing the giant: On the importance of rigour in documenting the literature search process. Paper presented at the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS).

Butt, M., and M. Aftab. 2013. Incorporating attitude towards Halal banking in an integrated service quality, satisfaction, trust and loyalty model in online Islamic banking context. International Journal of Bank Marketing 31 (1): 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652321311292029 .

Chamberlain, T., S. Hidayat, and A.R. Khokhar. 2020. Credit risk in Islamic banking: Evidence from the GCC. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 11 (5): 1055–1081. https://doi.org/10.1108/jiabr-09-2017-0133 .

Chattha, J.A., M.S. Alhabshi, and A.K.M. Meera. 2020. Risk management with a duration gap approach: Empirical evidence from a cross-country study of dual banking systems. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 11 (6): 1257–1300. https://doi.org/10.1108/jiabr-10-2017-0152 .

Chattha, J.A., and S.M. Alhabshi. 2018. Benchmark rate risk, duration gap and stress testing in dual banking systems, 62, 101063. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2018.08.017 .

Chong, B.S., and M.-H. Liu. 2009. Islamic banking: Interest-free or interest-based? Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 17 (1): 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2007.12.003 .

Choudhury, T.T., S.K. Paul, H.F. Rahman, Z. Jia, and N. Shukla. 2020. A systematic literature review on the service supply chain: Research agenda and future research directions. Production Planning & Control 31 (16): 1–22.

Čihák, M., and H. Hesse. 2010. Islamic Banks and Financial Stability: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Financial Services Research 38 (2): 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-010-0089-0 .

Cooper, H.M. 1988. Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowledge in Society 1 (1): 104.

Cox, S. 2005. Developing the Islamic capital market and creating liquidity. Review of Islamic Economics 9 (1): 75.

Daher, H., M. Masih, and M. Ibrahim. 2015. The unique risk exposures of Islamic banks’ capital buffers: A dynamic panel data analysis. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 36: 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2015.02.012 .

Dar, H.A., and J.R. Presley. 2000. Lack of profit loss sharing in Islamic banking: Management and control imbalances. International Journal of Islamic Financial Services 2 (2): 3–18.

David, R.J., and S.K. Han. 2004. A systematic assessment of the empirical support for transaction cost economics. Strategic Management Journal 25 (1): 39–58.

Effendi, K.A., and D. Disman. 2017. Liquidity risk: Comparison between Islamic and conventional banking. European Research Studies Journal. 20 (2A): 308–318. https://doi.org/10.35808/ersj/643 .

Elamer, A.A., C.G. Ntim, H.A. Abdou, and C. Pyke. 2019. Sharia supervisory boards, governance structures and operational risk disclosures: Evidence from Islamic banks in MENA countries. Global Finance Journal 46: 100488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2019.100488 .

Elgharbawy, A. 2020. Risk and risk management practices: A comparative study between Islamic and conventional banks in Qatar. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 11 (8): 1155–1581. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-06-2018-0080 .

Ergeç, E.H., and B.G. Arslan. 2013. Impact of interest rates on Islamic and conventional banks: The case of Turkey. Applied Economics 45 (17): 2381–2388. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2012.665598 .

Fakhfekh, M., N. Hachicha, F. Jawadi, N. Selmi, and A.I. Cheffou. 2016. Measuring volatility persistence for conventional and Islamic banks: An FI-EGARCH approach. Emerging Markets Review 27: 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2016.03.004 .

Fischl, M., M. Scherrer-Rathje, and T. Friedli. 2014. Digging deeper into supply risk: A systematic literature review on price risks. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 19 (5): 480–503. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-12-2013-0474 .

Gait, A. H., & Worthington, A. C. (2007). A primer on Islamic finance: Definitions, sources, principles and methods, University of Wollongong Research Online, Australia. Retrieved from https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/341

Gheeraert, L. 2014. Does Islamic finance spur banking sector development? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 103: S4–S20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.02.013 .

Gheeraert, L., and L. Weill. 2015. Does Islamic banking development favor macroeconomic efficiency? Evidence on the Islamic finance-growth nexus. Economic Modelling 47: 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2015.02.012 .

Ginena, K. 2014. Sharī‘ah risk and corporate governance of Islamic banks. Corporate Governance (bingley) 14: 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-03-2013-0038 .

Grassa, R. 2016. Ownership structure, deposits structure, income structure and insolvency risk in GCC Islamic banks. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 7 (2): 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-11-2013-0041 .

Hamid, B.A., W. Azmi, and M. Ali. 2020. Bank risk and financial development: Evidence from dual banking countries. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 56 (2): 286–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2019.1669445 .

Hamza, H., and Z. Saadaoui. 2013. Investment deposits, risk-taking and capital decisions in Islamic banks. Studies in Economics and Finance 30 (3): 244–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEF-Feb-2012-0016 .

Hassan, M.K., M. Rashid, A.S. Wei, B.O. Adedokun, and J. Ramachandran. 2019a. Islamic business scorecard and the screening of Islamic businesses in a cross-country setting. Thunderbird International Business Review 61 (5): 807–819.

Hassan, M.K., S. Aliyu, M. Huda, and M. Rashid. 2019b. A survey on Islamic Finance and accounting standards. Borsa Istanbul Review 19: S1–S13.

Hassan, M.K., A. Khan, and A. Paltrinieri. 2019c. Liquidity risk, credit risk and stability in Islamic and conventional banks. Research in International Business and Finance 48: 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2018.10.006 .

Hassan, M.K., O. Unsal, and H.E. Tamer. 2016. Risk management and capital adequacy in Turkish participation and conventional banks: A comparative stress testing analysis. Borsa Istanbul Review 16 (2): 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2016.04.001 .

Hernandez, J.A., K.H. Al-Yahyaee, S. Hammoudeh, and W. Mensi. 2019. Tail dependence risk exposure and diversification potential of Islamic and conventional banks. Applied Economics 51 (44): 4856–4869. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1602716 .

How, J.C., M.A. Karim, and P. Verhoeven. 2005. Islamic financing and bank risks: The case of Malaysia. Thunderbird International Business Review 47 (1): 75–94.

Ibrahim, M.H., and S.A.R. Rizvi. 2018. Bank lending, deposits and risk-taking in times of crisis: A panel analysis of Islamic and conventional banks. Emerging Markets Review 35: 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2017.12.003 .

Ibrahim, M.H., and F. Sufian. 2014. A structural VAR analysis of Islamic financing in Malaysia. Studies in Economics and Finance 31: 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEF-05-2012-0060 .

IFSB. (2020). Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report. Kuala Lumpur: IFSB.

Imam, P., and K. Kpodar. 2016. Islamic banking: Good for growth? Economic Modelling 59: 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.08.004 .

Kabir, M.N., A. Worthington, and R. Gupta. 2015. Comparative credit risk in Islamic and conventional bank. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 34: 327–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2015.06.001 .

Khan, F. 2010. How ‘Islamic’is Islamic banking? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 76 (3): 805–820.

Khediri, K.B., L. Charfeddine, and S.B. Youssef. 2015. Islamic versus conventional banks in the GCC countries: A comparative study using classification techniques. Research in International Business and Finance 33: 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2014.07.002 .

Kisman, Z. 2020. Risk management: Comparative study between Islamic banks and conventional banks. Journal of Economics and Business 3 (1): 232–237. https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1992.03.01.192 .

Kweh, Q.L., W.-M. Lu, M. Nourani, and M.H. Ghazali. 2018. Risk management and dynamic network performance: An illustration using a dual banking system. Applied Economics 50 (30): 3285–3299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1420889 .

Lassoued, M. 2018. Comparative study on credit risk in Islamic banking institutions: The case of Malaysia. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 70: 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2018.05.009 .

Lee, S.P., M. Isa, and N.A. Auzairy. 2020. The relationships between time deposit rates, real rates, inflation and risk premium: The case of a dual banking system in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 11 (5): 1033–1053. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-01-2018-0010 .

Louhichi, A., and Y. Boujelbene. 2016. Credit risk, managerial behaviour and macroeconomic equilibrium within dual banking systems: Interest-free vs. interest-based banking industries. Research in International Business and Finance 38: 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2016.03.014 .

Louhichi, A., S. Louati, and Y. Boujelbene. 2020. The regulations–risk taking nexus under competitive pressure: What about the Islamic banking system? Research in International Business and Finance . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.101074 .

Mahdi, I.B.S., and M.B. Abbes. 2018. Behavioral explanation for risk taking in Islamic and conventional banks. Research in International Business and Finance 45: 577–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.07.111 .

Masood, O., J. Younas, and M. Bellalah. 2017. Liquidity risk management implementation for selected Islamic banks in Pakistan. Journal of Risk 19 (S1): S57–S69. https://doi.org/10.21314/JOR.2017.375 .

Megeid, N.S.A. 2017. Liquidity risk management: Conventional versus Islamic banking system in Egypt. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 8 (1): 100–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-05-2014-0018 .

Mirza, N., B. Rahat, and K. Reddy. 2015. Business dynamics, efficiency, asset quality and stability: The case of financial intermediaries in Pakistan. Economic Modelling 46: 358–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2015.02.006 .

Mohamad, S., J. Othman, R. Roslin, and O.M. Lehner. 2014. The use of Islamic hedging instruments as non-speculative risk management tools. Venture Capital 16 (3): 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2014.922824 .

Mohammad, S., M. Asutay, R. Dixon, and E. Platonova. 2020. Liquidity risk exposure and its determinants in the banking sector: A comparative analysis between Islamic, conventional and hybrid banks. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 66: 101196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2020.101196 .

Mokni, R.B.S., A. Echchabi, D. Azouzi, and H. Rachdi. 2014. Risk management tools practiced in Islamic banks: Evidence in MENA region. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 5: 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-10-2012-0070 .

Mollah, S., M.K. Hassan, O. Al Farooque, and A. Mobarek. 2017. The governance, risk-taking, and performance of Islamic banks. Journal of Financial Services Research 51 (2): 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-016-0245-2 .

Neifar, S., and A. Jarboui. 2018. Corporate governance and operational risk voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Islamic banks. Research in International Business and Finance 46: 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.09.006 .

Newbert, S.L. 2007. Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strategic Management Journal 28 (2): 121–146.

Noor, N.S.M., M.H.M. Shafiai, and A.G. Ismail. 2019. The derivation of Shariah risk in Islamic finance: A theoretical approach. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 10 (5): 663–678. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-08-2017-0112 .

Oz, E., Ali, M. M., Khokher, Z. U. R., & Rosman, R. (2016). Sharī’ah Non-Compliance Risk in the Banking Sector: Impact on Capital Adequacy Framework of Islamic Banks. Working Paper Series: WP-05/03/2016, Kuala Lumpur: IFSB.

Paltrinieri, A., Dreassi, A., Rossi, S., & Khan, A. (2020). Risk-adjusted profitability and stability of Islamic and conventional banks: Does revenue diversification matter?. Global Finance Journal, In press, 100517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2020.100517

Pappas, V., S. Ongena, M. Izzeldin, and A.-M. Fuertes. 2017. A survival analysis of Islamic and conventional banks. Journal of Financial Services Research 51 (2): 221–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-016-0239-0 .

Rashid, M., J. Ramachandran, and T.S.B.T.M. Fawzy. 2017. Cross-country panel data evidence of the determinants of liquidity risk in Islamic banks: A contingency theory approach. International Journal of Business and Society 18 (S1): 3–22.

Rizwan, M.S., M. Moinuddin, B. L’Huillier, and D. Ashraf. 2018. Does a one-size-fits-all approach to financial regulations alleviate default risk? The case of dual banking systems. Journal of Regulatory Economics 53: 37–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-017-9340-z .

Rosly, S.A., M.A. Naim, and A. Lahsasna. 2017. Measuring Shariah non-compliance risk (SNCR): Claw-out effect of al-bai-bithaman ajil in default. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 8 (3): 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-02-2016-0018 .

Rosman, R., and A.R.A. Rahman. 2015. The practice of IFSB guiding principles of risk management by Islamic banks: International evidence. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 6 (2): 150–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-09-2012-0058 .

Rowley, J., and F. Slack. 2004. Conducting a literature review. Management Research News 27 (6): 31–39.

Saeed, M., and M. Izzeldin. 2016. Examining the relationship between default risk and efficiency in Islamic and conventional banks. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 132: 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.02.014 .

Safiullah, M., and A. Shamsuddin. 2018. Risk in Islamic banking and corporate governance. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 47: 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2017.12.008 .

Shah, S.A.A., R. Sukmana, and B.A. Fianto. 2020. Duration model for maturity gap risk management in Islamic banks. Journal of Modelling in Management 15 (3): 1167–1186. https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-08-2019-0184 .

Smaoui, H., K. Mimouni, and A. Temimi. 2020. The impact of Sukuk on the insolvency risk of conventional and Islamic banks. Applied Economics 52 (8): 806–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1646406 .

Sobarsyah, M., W. Soedarmono, W.S.A. Yudhi, I. Trinugroho, A. Warokka, and S.E. Pramono. 2020. Loan growth, capitalization, and credit risk in Islamic banking. International Economics 163: 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2020.02.001 .

Sorwar, G., V. Pappas, J. Pereira, and M. Nurullah. 2016. To debt or not to debt: Are Islamic banks less risky than conventional banks? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 132: 113–126.

Srairi, S. 2019. Transparency and bank risk-taking in GCC Islamic banking. Borsa Istanbul Review 19 (Supplement 1): 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2019.02.001 .

Srairi, S. 2013. Ownership structure and risk-taking behaviour in conventional and Islamic banks: Evidence for MENA countries. Borsa Istanbul Review 13 (4): 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2013.10.010 .

Toumi, K., J.-L. Viviani, and Z. Chayeh. 2019. Measurement of the displaced commercial risk in Islamic Banks. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 74: 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2018.03.001 .

Touri, O., R. Ahroum, and B. Achchab. 2020. Management and monitoring of the displaced commercial risk: A prescriptive approach. International Journal of Emerging Markets . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-07-2018-0407 .

Trad, N., M.A. Trabelsi, and J.F. Goux. 2017. Risk and profitability of Islamic banks: A religious deception or an alternative solution? European Research on Management and Business Economics 23: 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2016.09.001 .

Tranfield, D., D. Denyer, and P. Smart. 2003. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management 14 (3): 207–222.

Wahab, H.A., B. Saiti, S.A. Rosly, and A.M.M. Masih. 2017. Risk-Taking Behavior and Capital Adequacy in a Mixed Banking System: New Evidence from Malaysia Using Dynamic OLS and Two-Step Dynamic System GMM Estimators. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 53 (1): 180–198.

Warninda, T.D., I.A. Ekaputra, and R. Rokhim. 2019. Do Mudarabah and Musharakah financing impact Islamic Bank credit risk differently? Research in International Business and Finance 49: 166–175.

Wiryono, S.K., and K.A. Effendi. 2018. Islamic Bank Credit Risk: Macroeconomic and Bank Specific Factors. European Research Studies Journal 21 (3): 53–62.

Yahya, M.H., J. Muhammad, and A.R.A. Hadi. 2012. A comparative study on the level of efficiency between Islamic and conventional banking systems in Malaysia. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 5 (1): 48–62.

Zaher, T.S., and M. Hassan. 2001. A comparative literature survey of Islamic finance and banking. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments 10 (4): 155–199.

Zainol, Z., and S.H. Kassim. 2012. A critical review of the literature on the rate of return risk in Islamic banks. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 3: 121–137.

Zheng, C., S. Moudud-Ul-Huq, M.M. Rahman, and B.N. Ashraf. 2017. Does the ownership structure matter for banks’ capital regulation and risk-taking behavior? Empirical evidence from a developing country. Research in International Business and Finance 42: 404–421.

Zhou, G., and G. Ye. 1988. Forward-backward search method. Journal of Computer Science and Technology 3 (4): 289–305.

Zins, A., and L. Weill. 2017. Islamic banking and risk: The impact of Basel II. Economic Modelling 64: 626–637.

Zorn, T., and N. Campbell. 2006. Improving the writing of literature reviews through a literature integration exercise. Business Communication Quarterly 69 (2): 172–183.

Download references

We did not receive any funding to complete this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of New Orleans, New Orleans, USA

M. Kabir Hassan

University of Kent, Canterbury, UK

Md Nurul Islam Sohel

King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Tonmoy Choudhury

Christ Church Business School, Canterbury Christ Church University, Canterbury, UK

Mamunur Rashid

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mamunur Rashid .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A1: List of journals reviewed

Rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hassan, M.K., Sohel, M.N.I., Choudhury, T. et al. A systematic literature review of risks in Islamic banking system: research agenda and future research directions. Risk Manag 26 , 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41283-023-00135-z

Download citation

Accepted : 07 November 2023

Published : 20 December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41283-023-00135-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Islamic finance

- Islamic banking

- Risk management

- Systematic literature review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

12 Islamic banking: A Review of the Empirical Literature and Future Research Directions

Narjess Boubakri is the Bank of Sharjah Chair in Banking and Finance, Professor of Finance and Head of the Finance Department at the School of Business Administration of the American University of Sharjah. Her research interests include, among other things, privatization, corporate governance, political economy of reforms, institutional economics, and the impact of institutional infrastructure on corporations. Her papers have been published in the Journal of Finance, the Journal of Financial Economics, the Journal of International Business Studies, the Journal of Accounting Research, and the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, among others. She acts as Associate Editor for the Journal of Corporate Finance, as Editor in Chief for Finance Research Letters, co-editor for the Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, and is on the editorial boards of Emerging Markets Review and the Journal of International Financial Markets Institutions and Money.

Ruiyuan Ryan Chen is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the West Virginia University. His current research focuses on state ownership, corporate governance, and corporate cash holdings. His research has been published in Emerging Markets Review, the Journal of Corporate Finance, and the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis.

Omrane Guedhami is the C. Russell Hill Professor of Economics and Professor of International Finance at the Moore School of Business at the University of South Carolina. His current research focuses on corporate governance, privatization, corporate social responsibility, and formal and informal institutions and their effects on corporate policies and firm performance. His research has been published in the Journal of Financial Economics, the Journal of Accounting Research, the Journal of Accounting and Economics, the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, the Journal of International Business Studies, and Management Science, and the Review of Finance, among others. He is a member of the editorial boards of major journals, such as Contemporary Accounting Research and the Journal of International Business Studies, and is currently serving as a Section Editor at the Journal of Business Ethics and Associate Editor of the Journal of Corporate Finance and the Journal of Financial Stability.

Xinming Li is an Associate Professor of Finance at the School of Finance at Nankai University and a consultant at the World Bank Group. He is also the holder of the Emerging Scholars Award by the Federal Reserve and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors. His research areas include a variety of topics related to banking and financial institutions, corporate finance, and international finance.

- Published: 06 November 2019

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The last two decades have witnessed a tremendous global growth in Islamic finance and banking, mainly prompted by the global financial crisis. This growth has been accompanied by an increasing interest among researchers, policymakers, managers of financial institutions, and the public about the functionalities of the Islamic banking system and how it differs from conventional banking. Against this backdrop, we start this chapter with an overview and assessment of the practice of Islamic banking around the world. Then, we discuss its primary characteristics, including its underlying principles and common financial products. Next, we review the key findings in the empirical literature on the differences between Islamic and conventional banking at the micro and macro levels. We conclude with a discussion of avenues for future research.

12.1 Introduction

The last two decades have witnessed dramatic global growth in Islamic finance and banking. Since the founding of the first Islamic bank in 1975, Islamic financial assets in the banking, capital markets, and insurance sectors have reached over $2 trillion (IFSB, 2018 ), 1 and more than 350 Islamic banks now operate worldwide.

The term “Islamic banking” refers generally to banking operations conducted under Sharia law, which mandates banking transactions be subject to three sets of constraints. First, payments or receipts of interest ( Riba ), whether nominal or real, are prohibited. In this sense, Islamic banking is basically an interest-free model. Thus, because money cannot reward money, Islamic transactions must be backed by tangible assets. Second, Gharar and Maysar , speculation and excessive risk-taking or betting, respectively, are prohibited. In practice, this means, for example, that Islamic banks cannot trade derivative products. 2 Third, Islamic banks are prohibited from financing activities that are illegal under Islamic law, or that are viewed as having a negative impact on society, such as those involving alcohol or gambling.

In this chapter, we provide an overview and assessment of the practice of Islamic banking around the world. Section 12.2 provides a brief review of the growth of Islamic banking. In section 12.3 , we discuss its primary characteristics, including its underlying principles and common financial products. In sections 12.4 and 12.5 , we review key findings in the empirical literature on the differences between Islamic and conventional banking at the micro and macro levels. We conclude in section 12.6 with avenues for future research.

12.2 Growth of Islamic Banking around the World

Modern Islamic banking dates to the 1970s. The first international Islamic bank, the Islamic Development Bank (IDB), was founded in 1975 by members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. IDB’s aim was to cater to the Muslim population’s needs while fostering economic and social development in accordance with the principles of Sharia law, a set of Islamic principles derived from the Koran.

The first modern (private) Islamic bank, Dubai Islamic Bank, was also established in 1975. Although privately owned and operated, it relied on a committee of religious Sharia advisors to conduct its operations. Next, the Kuwait Finance House was established in 1977. Unlike Dubai Islamic Bank, Kuwait Finance House was majority owned by government ministries. Two additional Islamic banks were founded by governments in 1977, Faisal Islamic Bank of Sudan and Faisal Islamic Bank of Egypt. 3

During the 1980s, reforms in Iran and Sudan removed all interest-based operations from the banking sector, resulting in the first fully Islamic national banking systems (Wealth Monitor, 2016 ; Hassan and Aliyu, 2018 ). Islamic banks were also introduced in other countries with large Muslim populations, such as Malaysia, Bangladesh, Mauritania, and Saudi Arabia (Imam and Kpodar, 2016 ).

The 1990s witnessed a greater acceleration in the establishment of Islamic banks “after the applications of Islamic finance functions were acknowledged by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank [in] the early 1990s (Iqbal and Molyneux, 2005 )” (Alandejani, Kutan, and Samargandi, 2017 ). The pace quickened again after the global financial crisis (GFC), 4 because it cast doubts on the proper functioning of conventional banking, which, in turn, created interest in alternative models such as Islamic banking (Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Merrouche, 2013 ; Hassan and Aliyu, 2018 ).

Zaher and Hassan ( 2001 ) argue that the liberalization of capital markets, the global integration of financial markets, structural macroeconomic reforms, and the introduction of innovative Islamic products also contributed to the growth of Islamic banking. The substantial rise in consumer demand for Sharia -compliant contracts has led multinational banks such as Chase Bank, Citibank, ABN Amro, and HSBC to establish Islamic finance branches while conducting separate conventional banking operations.

In 1991, to support this growth, the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) was created to set accounting, auditing, and Sharia standards for Islamic financial institutions. In 2002, the AAOIFI was complemented by the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), which sets prudential standards and regulates the industry, and the International Islamic Financial Market (IIFM), which focuses on developing a robust, transparent, and efficient Islamic financial market. 5

As we note in the Introduction, today there are more than 350 Islamic banks worldwide, operating in countries as diverse as Switzerland, the US, France, Germany, Thailand, Singapore, India, China, and Australia. In January 2018, Islamic banking was also present in South America, where a conventional bank in Suriname was recently converted to a Sharia -compliant Islamic bank (IFSB, 2018 ). Despite the wide reach of Islamic banking, however, industry assets are highly concentrated in a small number of countries. In particular, the oil-exporting Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Malaysia, and Iran together account for more than 80 percent of the industry’s assets (Islamic Finance Outlook, 2018 ). 6

At a country level, as shown by Figure 12.1 , Iran has the largest share of the Islamic banking market with 34.4 percent of global Islamic banking assets, followed by Saudi Arabia (20.4 percent), United Arab Emirates (9.3 percent), Malaysia (9.1 percent), Kuwait (6 percent), and Qatar (6 percent) (IFSB, 2018 ). Within countries, the share of Islamic banking has been growing as well. For example, Islamic banking now accounts for 61.8 percent of the domestic market in Brunei, followed by Saudi Arabia at 51.5 percent of the domestic market (IFSB, 2018 ).

Shares of Global Islamic Banking Assets (1H2017).

Looking at different sectors of the Islamic banking industry, the IFSI Stability Report (IFSB, 2018 ) shows that assets and financing each grew at a compounded rate of 8.8 percent between 2013 and 2017, while deposits grew at a compounded rate of 9.4 percent over the same period. In countries with a smaller Islamic base, these growth rates have been even more notable. Oman, for example, saw increases in Islamic banking assets, financing, and deposits of more than 30 percent each in 2Q2017. In the United Arab Emirates, both Islamic banking assets and financing grew by 7.4 percent, exceeding the average asset growth of 4.9 percent for conventional banks over the 2Q2016-2Q2017 period.

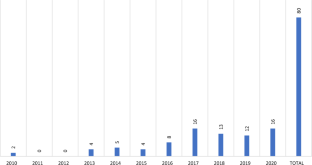

To provide further evidence on the worldwide growth of Islamic banking, we turn to Bankscope, 7 which contains detailed information about Islamic banking over the 1999–2014 period, and is widely viewed as an excellent source of information on Islamic finance. Figure 12.2 plots the number of Islamic banks between 1999 and 2014. As can be seen, the number reporting to Bankscope increased from thirty-six in 1999 to 104 in 2014, with a peak of 116 in 2011.

Figure 12.3 plots the total assets of Islamic banks. The figure shows that total assets increased dramatically, from around $18 billion in 1999 to $262 billion in 2014, with the level more than doubling after the GFC. In Figure 12.4 , we note that Islamic banks account for a small share of total bank assets globally—less than 3 percent of total banking sector assets in 2014—but, in Figure 12.5 , we see the share has been increasing. For example, in the twenty-eight countries with at least one Islamic bank over the 1999–2014 period, the proportion of Islamic bank assets increased from less than 1 percent in 1999 to a peak of more than 3 percent in 2013. Figure 12.5 shows that, in a large number of countries, and mainly in GCC countries, Islamic banks account for a significant share of assets in the domestic market. Note that the entire banking systems of Iran and Sudan are Islamic, while in Brunei they account for more than 57 percent, followed by Saudi Arabia (51.1 percent), and Kuwait (39 percent).

Number of Islamic Banks Reporting to Bankscope.

Islamic Banks’ Total Assets (million $).

Share of Islamic Banks’ Assets in Total Banking Sector Assets (%).

Share of Islamic Banks’ Assets in Total Banking Sector by Country (1H2016).

Looking ahead, Islamic banking is expected to continue growing. Imam and Kpodar ( 2013 ) show that factors contributing to the development of Islamic banking in a given country include the size of the Muslim population, income per capita, the level of interest rates, whether the country is a net exporter of oil, the size of trade with the Middle East, the level of economic stability, and proximity to Malaysia and Bahrain (two Islamic financial centers). However, while important for conventional banking, they find that the quality of a country’s institutional environment does not matter for the diffusion of Islamic banking. 8 As Figure 12.6 shows, the Muslim population is projected to increase from 1.3 billion in 2010 to over 1.6 billion in 2030. Because people in countries where the majority of residents identify as Muslim tend to have at least some familiarity with Islamic banking (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2014 ), growth in the world’s Muslim population alone supports an increase in Islamic banking over time. The fact that Islamic banks are regarded as following an ethically and socially responsible business model and are perceived to show higher resilience during times of economic distress are likely to further contribute to the growth.

World Islamic Population 1990, 2010, and 2030 (millions).

12.3 Characteristics of Islamic Banking

12.3.1 islamic banking: underlying principles.

Islamic banks follow the religious principles of equity, participation, and ownership as embedded in Sharia law. Accordingly, as we discuss above, Islamic banks cannot charge predetermined interest rates ( Riba ), take excessive risk, speculate ( Gharar ), or bet ( Maysar ), and they are prohibited from trading in asset classes associated with illegal activity or negative social outcomes, such as alcohol, drugs, and weapons. As Zaher and Hassan ( 2001 , p. 158) put it, “exploitative contracts based on Riba (interest or usury) or unfair contracts that involve risk or speculation” are prohibited.

To elaborate, Riba —an important feature of conventional banking—corresponds to the “fixing in advance of a positive return on a loan as a reward for waiting to be repaid” (Zaher and Hassan, 2001 , p. 156). The prohibition of Riba , which is an increase in money not connected to a tangible real economic increase, is consistent with the principle of equity. Thus, the weaker contracting party in a financial transaction is protected from an increase in wealth that is not related to a productive activity (Hussain, Shahmoradi, and Turk, 2015 ). Moreover, the prohibition of Riba is consistent with the principle of participation, which ensures both borrower and lender share in the risk of a project (Zaher and Hassan, 2001 ). The prohibition of Gharar , or excessive risk-taking, is similarly in line with the equity principle, as it decreases information asymmetry and contract ambiguity. Instead, Islamic banks rely on the idea of risk sharing on both the liability and asset side. They also follow the idea “that all transactions have to be backed by a real economic transaction that involves a tangible asset” (Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Merrouche, 2013 , p. 433), which is in line with the participation and ownership principles. For example, profit-and-loss sharing involve providing financing to anyone with a productive business venture idea. The borrower and the lender work closely together and share the risk of the venture, which is selected based on its projected returns. The return earned on capital is thus associated with productive activity, is backed by an asset (i.e., the requirement of asset ownership before a return can be earned), and is determined only ex post by the asset’s performance and not the passage of time (Hussain, Shahmoradi, and Turk, 2015 , p. 6). This idea of “zero risk entails zero return,” where risk relates “primarily to the real-sector uncertainties, not the risk of borrower delinquency” (Ariff, 2014 , p. 734), is a key feature of Islamic banking. Under this framework, Zaher and Hassan ( 2001 ) argue that depositors in Islamic banks can be viewed as “shareholders,” because they earn dividends when the bank makes a profit and lose money when the bank records a loss.

The principles above are at the core of the differences between Islamic and conventional banking systems, as summarized by Errico and Farahbaksh ( 1998 ) and illustrated in Table 12.1 .

12.3.2 Islamic Banking: Financial Products

Islamic scholars have developed several Sharia -compliant financial instruments that not only avoid the payment or receipt of interest at a predetermined rate (Čihák and Hesse, 2010 ), but also include risk sharing. These Islamic financial contracts fall into two asset categories: equity and debt. Table 12.2 summarizes the six basic Islamic finance instruments, which are discussed in more detail next.

On the equity side, Islamic banks offer Mudaraba (silent partnership) and Musharaka (joint partnership) contracts. A Mudaraba contract is structured as a profit-sharing and loss-bearing contract, whereby a principal (the bank or investor) provides funds to an agent (entrepreneur), who in turn provides effort and management expertise for the project. Under this contract, although the entrepreneur controls and runs the business, the bank that provides the capital can participate in the decision-making. In this case, losses are borne exclusively by the bank, while profits are shared at a pre-agreed percentage. This structure is comparable to conventional limited partnerships.

A Musharaka contract is an alternative profit-and-loss partnership arrangement. Under this type of agreement, two parties (the bank and the client) provide the capital needed to finance a project, so profits as well as losses are shared by both parties. Here, profits are shared based on a pre-agreed percentage, while losses are shared in proportion to each party’s equity participation. This type of contract comes closest to the principles of equity and participation that form the basis of Sharia law, since it involves risk sharing, asset ownership, and no interest. It is most suitable for financing long-term projects.

On the debt side, Islamic banks offer Murabaha, Ijara, Salam , and Istisna . A Murabaha contract is a cost-plus-profit transaction commonly used for consumer loans, trade finance, corporate credit, real estate, and project financing. Under this type of contract, the Islamic bank purchases goods on behalf of the customer and then resells them to the customer at a mark-up. This type of contract is essentially an asset-backed loan plus a deferred payment sale transaction. The contract terms cannot be altered during the life of the contract, even if the client defaults or is late making payments. The mark-up is determined based on LIBOR, the type of good being financed, the overall amount of the transaction, and the client’s credit history. Under this type of contract, the benefits and risks of asset ownership are transferred to the client along with ownership, but the bank shares in the project’s risk because it assumes liability if the goods it purchased were defective. In case of default, however, the ownership rights of the asset return to the bank.

Under an Ijara contract, the bank retains ownership of the goods, leasing them out for pre-agreed payments (to avoid speculation) over a pre-agreed period of time, just as in a conventional leasing contract. Because the bank owns the asset, it assumes responsibility for its maintenance and insurance. Ijara payments can be changed during the contract period, unlike Murabaha payments.

A Salam contract is a forward agreement whereby delivery occurs at a future date in exchange for spot payments. According to Hussain, Shahmoradi, and Turk ( 2015 , p. 9), “Such transactions were originally allowed to meet the financing needs of small farmers as they were unable to yield adequate returns until several periods after the initial investment.” To be Sharia -compliant, payment under these contracts must be made in full at the beginning of the contract period. This type of contract thus entails a spot obligation for the client and a future obligation for the bank.

Under the last type of debt contract, Istisna , both payment and delivery occur in the future. This type of contract is effectively a pre-delivery financing and leasing contract. It is used primarily to finance large-scale, long-term projects (Zaher and Hassan, 2001 ). Notably, Istisna is a three-party contract. The bank acts as an intermediary between the client, from which it receives payments, and the manufacturer, to which it makes installment payments, because it is the bank that commits to buying the assets. Of the various types of debt instruments in Islamic banking, the last two types, Salam and Istisna , are used least often.

In practice, several of these Sharia -compliant products do not appear to differ that much from conventional products. This is because of the “close alignment of the competitive rates paid by Islamic banks on investment deposits with deposit rates at conventional banks, as well as with the benchmarking of Islamic financing rates on the asset side of the balance sheet to the LIBOR” (Hussain, Shahmoradi, and Turk, 2015 , p. 12). 9 Moreover, in terms of their business models, Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Merrouche ( 2013 ) and Čihák and Hesse ( 2010 ) find few significant differences in business orientation, asset quality, efficiency, or stability between Islamic and conventional banking. However, a closer look at the two sets of products reveals major differences in terms of asset ownership, 10 interest, equity, and risk sharing, as explained above. Moreover, there are differences in the degree of permissibility of some Sharia -compliant products from one country to another (Song and Oosthuizen, 2014 ). For example, Tawarruq , instruments used by Islamic banks to fulfill clients’ demands to extend personal loans, are permitted in the UAE but not in Iran.

The most recent Stability Report (IFSB, 2018 , p. 88) reports that household and personal financing constitute the main financing activities of Islamic banks (42 percent of total Islamic bank financing in 2017) (p. 94), followed by manufacturing and retail trade with 21 percent. In terms of contracts, Murabaha and Ijara dominate Islamic banking transactions, accounting for up to 7 percent. In comparison, profit-and-loss-sharing contracts represent only 5 percent of transactions with Islamic banks (Hassan and Aliyu, 2018 ). In Oman, where Islamic banking is growing at the fastest rate, Musharaka and Ijara account for 76.5 percent of total financing by Islamic banks, with these contracts used largely for real estate purchases and consumer financing (IFSB, 2018 ).

12.3.3 Islamic Banking versus Conventional Banking Balance Sheets

Van Greuning and Iqbal ( 2007 ) provide a detailed comparison of the balance sheets of a conventional bank (Table 12.3 ) and an Islamic bank (Table 12.4 ), highlighting differences in terms of risk. For a conventional bank, the liability side includes demand and savings deposits, term certificates, and capital. The asset side includes marketable securities, lending to consumers (individuals/households) and corporations, and trading accounts. According to van Greuning and Iqbal ( 2007 , chapter 2 , pp. 16–21), this structure (1) generates an asset-liability mismatch, because “the deposits create instantaneous pre-determined liabilities irrespective of the outcome of the usage of the funds on the asset side,” and (2) exposes the bank to maturity mismatch risk, reducing their incentives to fund long-term non-liquid projects because “medium- to long-term assets are financed by the stream of short-term liabilities.” Because they do not typically have access to traditional money markets, managing short-term liquidity positions in Islamic banks can be challenging.