Introduction to Emotional Intelligence

Cite this chapter.

- Aruna Chakraborty &

- Amit Konar

Part of the book series: Studies in Computational Intelligence ((SCI,volume 234))

3356 Accesses

2 Citations

This chapter provides an introduction to emotional intelligence. It attempts to define emotion from different perspectives, and explores possible causes and varieties. Typical characteristics of emotion, such as great intensity, instability, partial perspectives and brevity are outlined next. The evolution of emotion arousal through four primitive phases such as cognition, evaluation, motivation and feeling is briefly introduced. The latter part of the chapter emphasizes the relationship between emotion and rational reasoning. The biological basis of emotion and the cognitive model of its self-regulation are discussed at the end of the chapter.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Albus, J.A.: Meystel, Engineering of the Mind: An Introduction to the Science of Intelligent Systems. Wiley, New York (2001)

Google Scholar

Alvarez, P., Squire, L.R.: Memory consolidation and the medial temporal lobe; a simple network model. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 91, 4045–7041 (1994)

Bar-On, R.: Emotional and Social Intelligence: Insights from the Emotional Quotient Inventory. In: Bar-On, R., Parker, J.D.A. (eds.) The handbook of Emotional Intelligence, pp. 363–388. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco (2000)

Bechara, A., Tranel, D., Damasio, A.R.: Poor Judgement in spite of High Intellect: neurological Evidence for Emotional Intelligence. In: Bar-On, R., Parker, J.D.A. (eds.) Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco (2000)

Ben-Zéev, A.: The Subtlety of Emotions. MIT Press, Cambridge (2000)

Biehl, M., Matsumoto, D., Ekman, P., Hearn, V., Heider, K., Kudoh, T., Ton, K.: Matsumoto and Ekman’s Japanese and Caucasian Facial Expressions of Emotion (JACFEE): Reliability data and cross-national difference. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 21, 3–21 (1997)

Article Google Scholar

Buchel, C., Dolan, R.J., Armony, J.L., Friston, K.J.: Amygdalae-Hippocampal involvement in human aversive trace conditioning revealed through event-related functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. The Journal of Neuroscience 19 (December 15, 1999)

Carver, C.S., Scheier, M.F.: Attention and Self-Regulation: A Control-Theory Approach to Human Behavior. Springer, Berlin (1981)

Carver, C.S., Scheier, M.F.: Autonomy and Self-Regulation. Psychological Inquiry 11, 284–291 (2000)

Carver, C.S., Scheier, M.F.: On the Self-regulation of Behavior. Cambridge University Press, New York (1998)

Carver, C.S., Scheier, M.F.: On the Structure of Behavioral Self-Regulation. In: Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, D., Zeidher, M. (eds.) Handbook of Self-Regulation, pp. 41–84. Academic Press, San Diego (2000)

Chapter Google Scholar

Damasio, A.R.: The brain binds entities and events by multiregional activation from convergence zones. In: Gtfreund, H., Toulouse, G., et al. (eds.) Biology and Computation: A Physicist’s Choice, pp. 749–758. World Scientific, Singapore (1994)

Friston, K.J., Toroni, G., Reeke Jr., G.N., Sporns, O., Edelman, G.M.: Value-dependent selection in the brain: Simulation in a synthetic neural model. Neuroscience 59, 229–243 (1994)

Goleman, D.: Emotional Intelligence. Bantam Books, New York (1995)

Guyton, A.C., Hall, J.E.: Text Book of Medical Physiology. Harcourt Brace & Company Asia PTE LTD, Saunders (1998)

Kant, I.: Groundwork of the metaphysics of morals. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1998)

Konar, A.: Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing: Behavioral and Cognitive Modeling of the Human Brain. CRC Press, Boca Raton (1999)

Lazarus, R.S.: Stress and Emotions. A New Synthesis. Springer, New York (1999)

Lazarus, R.: Emotion and Adaptation. Oxford University Press, New York (1991)

Le Doux, J.E.: Emotion: Clues from the Brain. Annual Review of Psychology 46, 209–235 (1995)

Mattthews, G., Zeidner, M., Roberts, R.D.: Emotional Intelligence: Science and Myth, Bradford Book. MIT Press, Cambridge (2004)

Mayer, J.D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D.R.: Emotional Intelligence as Zeitgeist, as personality, and as a mental ability. In: Bar-On, R., Parker, J.D.A. (eds.) The handbook of emotional intelligence. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco (2000)

Mayer, J.D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D.R.: Competing models of emotional intelligence. In: Sternberg, R.J. (ed.) Handbook of human intelligence. Cambridge University Press, New York (2000)

McGaugh, J.L., Cahill, L., Roozendaal, B.: Involvement of the amygdala in memory storage: Interaction with other brain systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93, 13508–13514 (1996)

Panksepp, J.: Affective Neuroscience: The Foundation of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press, New York (1998)

Panksepp, J.: Towards a general psychological theory of emotions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 5, 407–467 (1982)

Rolls, E.T.: The Brain and Emotion. Oxford University Press, New York (1999)

Russell, S., Norvig, P.: Artificial Intelligence A Modern Approach. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs (1995)

MATH Google Scholar

Salovey, P., Bedell, B.T., Detweiler, J.B., Mayer, J.D.: Coping Intelligently: Emotional Intelligence and the Coping process. In: Snyder, C.R. (ed.) Coping: The Psychology of what works, pp. 141–164. Oxford University, New York (1999)

Schultz, W., Dayan, P., Montague, P.R.: A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275, 1593–1599 (1997)

Senior, C., Russell, T., Gazzaniga, M.S.: Methods in Mind. The MIT Press, Cambridge (2006)

Shallice, T., Burgers, P.: The domain of supervisory processes and the temporal organization of behavior. In: Roberts, A.C., Robbins, T.W. (eds.) The prefrontal cortex: Executive and Cognitive functions, pp. 22–35. Oxford University Press, New York (1996)

Simon, H.A.: Motivational and Emotional Controls of Cognition. Psychological Review 74, 29–39 (1967)

Solomon, R.C.: The Philosophy of Emotions. In: Lewis, M., Haviland, J.M. (eds.) Handbook of Emotions. Guilford Press, New York (1993)

Wells, A., Matthews, G.: Attention and Emotion: A Clinical Perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hove (1994)

Zanden, J.W.V., Crandell, T.L., Crandell, C.H.: Human Development. McGraw-Hill, New York (2006)

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Chakraborty, A., Konar, A. (2009). Introduction to Emotional Intelligence. In: Emotional Intelligence. Studies in Computational Intelligence, vol 234. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-68609-5_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-68609-5_1

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-540-68606-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-540-68609-5

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

REVIEW article

The measurement of emotional intelligence: a critical review of the literature and recommendations for researchers and practitioners.

- 1 School of Management, QUT Business School, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 2 Clinical Skills Development Service, Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Queensland Health, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 3 School of Psychology, Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD, Australia

- 4 School of Advertising, Marketing and Public Relations, QUT Business School, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Emotional Intelligence (EI) emerged in the 1990s as an ability based construct analogous to general Intelligence. However, over the past 3 decades two further, conceptually distinct forms of EI have emerged (often termed “trait EI” and “mixed model EI”) along with a large number of psychometric tools designed to measure these forms. Currently more than 30 different widely-used measures of EI have been developed. Although there is some clarity within the EI field regarding the types of EI and their respective measures, those external to the field are faced with a seemingly complex EI literature, overlapping terminology, and multiple published measures. In this paper we seek to provide guidance to researchers and practitioners seeking to utilize EI in their work. We first provide an overview of the different conceptualizations of EI. We then provide a set of recommendations for practitioners and researchers regarding the most appropriate measures of EI for a range of different purposes. We provide guidance both on how to select and use different measures of EI. We conclude with a comprehensive review of the major measures of EI in terms of factor structure, reliability, and validity.

Overview and Purpose

The purpose of this article is to review major, widely-used measures of Emotional Intelligence (EI) and make recommendations regarding their appropriate use. This article is written primarily for academics and practitioners who are not currently experts on EI but who are considering utilizing EI in their research and/or practice. For ease of reading therefore, we begin this article with an introduction to the different types of EI, followed by a brief summary of different measures of EI and their respective facets. We then provide a detailed set of recommendations for researchers and practitioners. Recommendations focus primarily on choosing between EI constructs (ability EI, trait EI, mixed models) as well as choosing between specific tests. We take into account such factors as test length, number of facets measured and whether tests are freely available. Consequently we also provide recommendations both for users willing to purchase tests and those preferring to utilize freely available measures.

In our detailed literature review, we focus on a set of widely used measures and summarize evidence for their validity, reliability, and conceptual basis. Our review includes studies that focus purely on psychometric properties of EI measures as well as studies conducted within applied settings, particularly health care settings. We include comprehensive tables summarizing key empirical studies on each measure, in terms of their research design and main findings. Our review includes measures that are academic and/or commercial as well as those that are freely available or require payment. To assist users with accessing measures, we include web links to complete EI questionaries for freely available measures and to websites and/or example items for copyrighted measures. For readers interested in reviews relating primarily to EI constructs, theory and outcomes rather than specifically measures of EI, we recommend a number of recent high quality publications (e.g., Kun and Demetrovics, 2010 ; Gutiérrez-Cobo et al., 2016 ). Additionally, for readers interested in a review of measures without the extensive recommendations we provide here, we recommend the chapter by Siegling et al. (2015) .

Early Research on Emotional Intelligence

EI emerged as a major psychological construct in the early 1990s, where it was conceptualized as a set of abilities largely analogous to general intelligence. Early influential work on EI was conducted by Salovey and Mayer (1990) , who defined EI as the “the ability to monitor one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions” (p. 189). They argued that individuals high in EI had certain emotional abilities and skills related to appraising and regulating emotions in the self and others. Accordingly, it was argued that individuals high in EI could accurately perceive certain emotions in themselves and others (e.g., anger, sadness) and also regulate emotions in themselves and others in order to achieve a range of adaptive outcomes or emotional states (e.g., motivation, creative thinking).

However, despite having a clear definition and conceptual basis, early research on EI was characterized by the development of multiple measures (e.g., Bar-On, 1997a , b ; Schutte et al., 1998 ; Mayer et al., 1999 ) with varying degrees of similarity (see Van Rooy et al., 2005 ). One cause of this proliferation was the commercial opportunities such tests offered to developers and the difficulties faced by researchers seeking to obtain copyrighted measures (see section Mixed EI for a summary of commercial measures). A further cause of this proliferation was the difficulty researchers faced in developing measures with good psychometric properties. A comprehensive discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this article (see Petrides, 2011 for more details) however one clear challenge faced by early EI test developers was constructing emotion-focused questions that could be scored with objective criteria. In comparison to measures of cognitive ability that have objectively right/wrong answers (e.g., mathematical problems), items designed to measure emotional abilities often rely on expert judgment to define correct answers which is problematic for multiple reasons ( Roberts et al., 2001 ; Maul, 2012 ).

A further characteristic of many early measures was their failure to discriminate between measures of typical and maximal performance. In particular, some test developers moved away from pure ability based questions and utilized self-report questions (i.e., questions asking participants to rate behavioral tendencies and/or abilities rather than objectively assessing their abilities; e.g., Schutte et al., 1998 ). Other measures utilized broader definitions of EI that included social effectiveness in addition to typical EI facets (see Ashkanasy and Daus, 2005 ) (e.g., Boyatzis et al., 2000 ; Boyatzis and Goleman, 2007 ). Over time it became clear that these different measures were tapping into related, yet distinct underlying constructs. Currently, there are two popular methods of classifying EI measures. First is the distinction between trait and ability EI proposed initially by Petrides and Furnham (2000) and further clarified by Pérez et al. (2005) . Second is in terms of the three EI “streams” as proposed by Ashkanasy and Daus (2005) . Fortunately there is overlap between these two methods of classification as we discuss below.

Methods of Classifying EI

The distinction between ability EI and trait EI first proposed by Petrides and Furnham (2000) was based purely on whether the measure was a test of maximal performance (ability EI) or a self-report questionnaire (trait EI) ( Petrides and Furnham, 2000 ; Pérez et al., 2005 ). According to this method of classification, Ability EI tests measure constructs related to an individual's theoretical understanding of emotions and emotional functioning, whereas trait EI questionnaires measure typical behaviors in emotion-relevant situations (e.g., when an individual is confronted with stress or an upset friend) as well as self-rated abilities. Importantly, the key aspect of this method of classification is that EI type is best defined by method of measurement: all EI measures that are based on self-report items are termed “trait EI” whereas all measures that are based on maximal performance items are termed “ability EI”.

The second popular method of classifying EI measures refers the three EI “streams” ( Ashkanasy and Daus, 2005 ). According to this method of classification, stream 1 includes ability measures based on Mayer and Salovey's model; stream 2 includes self-report measures based on Mayer and Salovey's model and stream 3 includes “expanded models of emotional intelligence that encompass components not included in Salovey and Mayer's definition” (p. 443). Ashkanasy and Daus (2005) noted that stream 3 had also been referred to as “mixed” models in that they comprise a mixture of personality and behavioral items. The term “mixed EI” is now frequently used in the literature to refer to EI measures that measure a combination of traits, social skills and competencies and overlaps with other personality measures ( O'Boyle et al., 2011 ).

Prior to moving on, we note that Petrides and Furnham's (2000 ) trait vs. ability distinction is sufficient to categorize the vast majority of EI tests. Utilizing this system, both stream 2 (self-report) and stream 3 (self-report mixed) are simply classified as “trait” measures. Indeed as argued by Pérez et al. (2005) , this method of classification is probably sufficient given that self-report measures of EI tend to correlate strongly regardless of whether they are stream 2 or stream 3 measures. However, given that the terms “stream 3” and “mixed” are so extensively used in the EI literature, we will also use them here. We are not proposing that these terms are ideal or even useful when classifying EI, but rather we wish to adopt language that is most representative of the existing literature on EI. In the following section therefore, we refer to ability EI (stream 1), trait EI (steam 2), and mixed EI (stream 3). As outlined later, decisions regarding which measure of EI to use should be based on what form of EI is relevant to a particular research project or professional application.

For the purposes of this review, we refer to “ability” based measures as tests that utilize questions/items comparable to those found in IQ tests (see Austin, 2010 ). These include all tests containing ability-type items and not only those based directly on Mayer and Salovey's model. In contrast to trait based measures, ability measures do not require that participants self-report on various statements, but rather require that participants solve emotion-related problems that have answers that are deemed to be correct or incorrect (e.g., what emotion might someone feel prior to a job interview? (a) sadness, (b) excitement, (c) nervousness, (d) all of the above). Ability based measures give a good indication of individuals' ability to understand emotions and how they work. However since they are tests of maximal ability, they do not tend to predict typical behavior as well as trait based measures (see O'Connor et al., 2017 ). Nevertheless, ability-based measures are valid, albeit weak, predictors of a range of outcomes including work related attitudes such as job satisfaction ( Miao et al., 2017 ), and job performance ( O'Boyle et al., 2011 ).

In this review, we define trait based measures as those that utilize self-report items to measure overall EI and its sub dimensions. We utilize this term for measures that are self-report, and have not explicitly been termed as “mixed” or “stream 3” by others. Individuals high in various measures of trait EI have been found to have high levels of self-efficacy regarding emotion-related behaviors and tend to be competent at managing and regulating emotions in themselves and others. Also, since trait EI measures tend to measure typical behavior rather than maximal performance, they tend to provide a good prediction of actual behaviors in a range of situations ( Petrides and Furnham, 2000 ). Recent meta-analyses have linked trait EI to a range of work attitudes such as job satisfaction and organization commitment ( Miao et al., 2017 ), Job Performance ( O'Boyle et al., 2011 ).

As noted earlier, although the majority of EI measures can be categorized using the terms “ability EI” and “trait EI”, we adopt the term “mixed EI” in this review when this term has been explicitly used in our source articles. The term mixed EI is predominately used to refer to questionnaires that measure a combination of traits, social skills and competencies that overlap with other personality measures. Generally these measures are self-report, however a number also utilize 360 degree forms of assessment (self-report combined with multiple peer reports from supervisors, colleagues and subordinates) (e.g., Bar-On, 1997a , b ) This is particularly true for commercial measures designed to predict and improve performance in the workplace. A common aspect in many of these measures is the focus on emotional “competencies” which can theoretically be developed in individuals to enhance their professional success (See Goleman, 1995 ). Research on mixed measures have found them to be valid predictors of multiple emotion-related outcomes including job satisfaction, organizational commitment ( Miao et al., 2017 ), and job performance ( O'Boyle et al., 2011 ). Effect sizes of these relationships tend to be moderate and on par with trait-based measures.

We note that although different forms of EI have emerged (trait, ability, mixed) there are nevertheless a number of conceptual similarities in the majority of measures. In particular, the majority of EI measures are regarded as hierarchical meaning that they produce a total “EI score” for test takers along with scores on multiple facets/subscales. Additionally, the facets in ability, trait and mixed measures of EI have numerous conceptual overlaps. This is largely due to the early influential work of Mayer and Salovey. In particular, the majority of measures include facets relating to (1) perceiving emotions (in self and others), (2) regulating emotions in self, (3) regulating emotions in others, and (4) strategically utilizing emotions. Where relevant therefore, this article will compare how well different measures of EI assess the various facets common to multiple EI measures.

Emotional Intelligence Scales

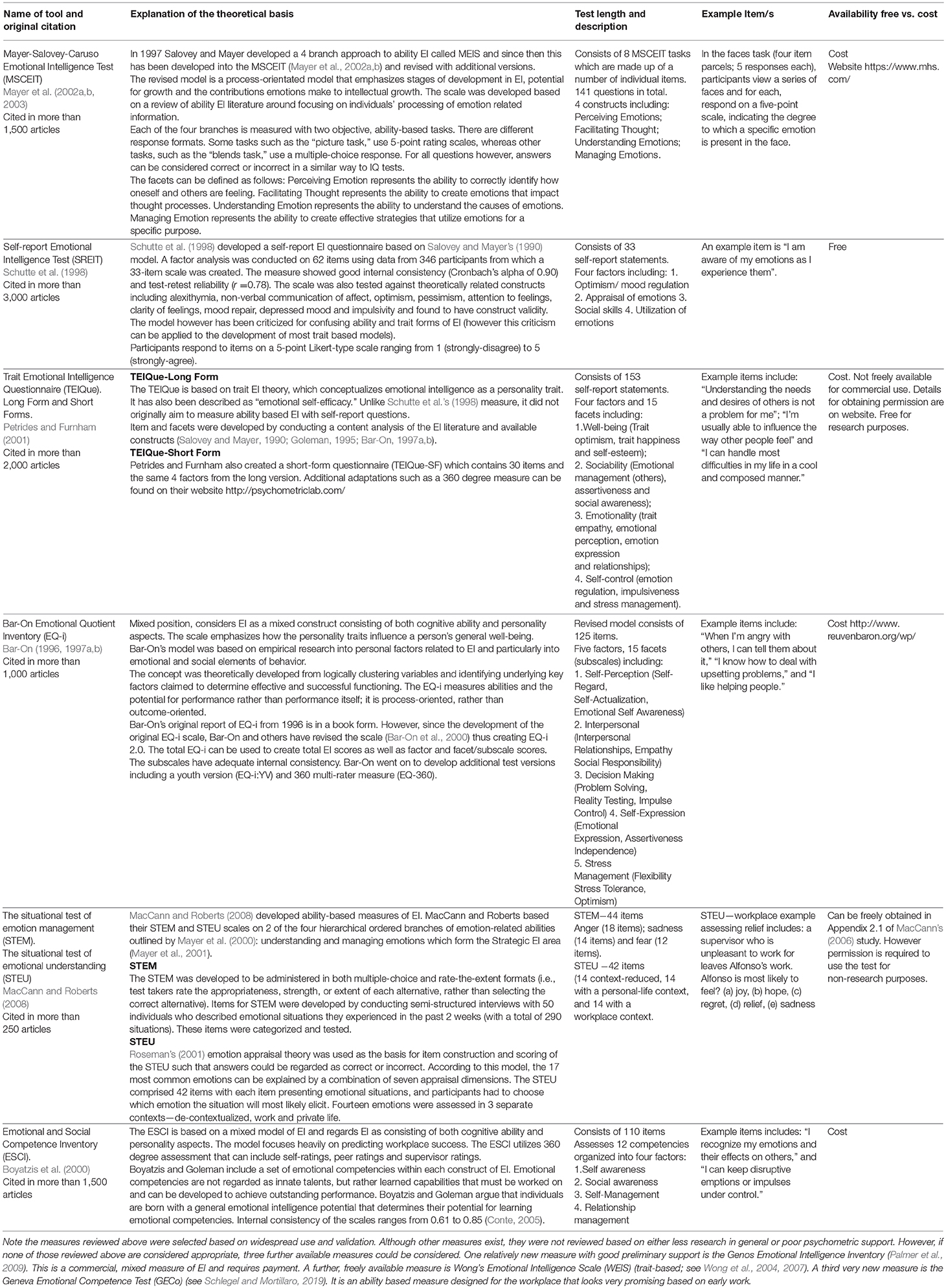

The following emotional intelligence scales were selected to be reviewed in this article because they are all widely researched general measures of EI that also measure several of the major facets common to EI measures (perceiving emotions, regulating emotions, utilizing emotions).

1. Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Tests (MSCEIT) ( Mayer et al., 2002a , b ).

2. Self-report Emotional Intelligence Test (SREIT) ( Schutte et al., 1998 )

3. Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue) ( Petrides and Furnham, 2001 )

4. Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) ( Bar-On, 1997a , b )

5. i) The Situational Test of Emotional Management (STEM) ( MacCann and Roberts, 2008 )

ii) The Situational Test of Emotional Understanding (STEU) ( MacCann and Roberts, 2008 )

6. Emotional and Social competence Inventory (ESCI) ( Boyatzis and Goleman, 2007 )

The complete literature review of these measures is included in the Literature Review section of this article. The following section provides a set of recommendations regarding which of these measures is appropriate to use across various research and applied scenarios.

Recommendations Regarding the Appropriate Use of Measures

Deciding between measuring trait ei, ability ei and mixed ei.

A key decision researchers/practitioners need to make prior to incorporating EI measures into their work is whether they should utilize a trait, ability or mixed measure of EI. In general, we suggest that when researchers/practitioners are interested in emotional abilities and competencies then they should utilize measures of ability EI. In particular ability EI is important in situations where a good theoretical understanding of emotions is required. For example a manager high in ability EI is more likely to make good decisions regarding team composition. Indeed numerous studies on ability EI and decision making in professionals indicates that those high in EI tend to be competent decision makers, problem solvers and negotiators due primarily to their enhanced abilities at perceiving and understanding emotions (see Mayer et al., 2008 ). More generally, ability EI research also has demonstrated associations between ability EI and social competence in children ( Schultz et al., 2004 ) and adults ( Brackett et al., 2006 ).

We suggest that researchers/practitioners should select trait measures of EI when they are interested in measuring behavioral tendencies and/or emotional self-efficacy. This should be when ongoing, typical behavior is likely to lead to positive outcomes, rather than intermittent, maximal performance. For example, research on task-induced stress (i.e., temporary states of negative affect evoked by short term, challenging tasks) has shown trait EI to have incremental validity over other predictors ( O'Connor et al., 2017 ). More generally, research tends to show that trait EI is a good predictor of effective coping styles in response to life stressors (e.g., Austin et al., 2010 ). Overall, trait EI is associated with a broad set of emotion and social related outcomes adults and children ( Mavroveli and Sánchez-Ruiz, 2011 ; Petrides et al., 2016 ) Therefore in situations characterized by ongoing stressors such as educational contexts and employment, we suggest that trait measures be used.

When both abilities and traits are important, researchers/practitioners might choose to use both ability and trait measures. Indeed some research demonstrates that both forms of EI are important stress buffers and that they exert their protective effects at different stages of the coping process: ability EI aids in the selection of coping strategies whereas trait EI predicts the implementation of such strategies once selected ( Davis and Humphrey, 2014 ).

Finally, when researchers/practitioners are interested in a broader set of emotion-related and social-related dispositions and competencies we recommend a mixed measure. Mixed measures are particularly appropriate in the context of the workplace. This seems to be the case for two reasons: first, the tendency to frame EI as a set of competencies that can be trained (e.g., Goleman, 1995 ; Boyatzis and Goleman, 2007 ) is likely to equip workers with a positive growth mindset regarding their EI. Second, the emphasis on 360 degree forms of assessment in mixed measures provides individuals with information not only on their self-perceptions, but on how others perceive them which is also particularly useful in training situations.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Trait and Ability EI

There are numerous advantages and disadvantages of the different forms of EI that test users should factor into their decision. One disadvantage of self-report measures is that people are not always good judges of their emotion-related abilities and tendencies ( Brackett et al., 2006 ; Sheldon et al., 2014 ; Boyatzis, 2018 ). A further disadvantage of self-report, trait based measures is their susceptibility to faking. Participants can easily come across as high in EI by answering questions in a strategic, socially desirable way. However, this is usually only an issue when test-takers believe that someone of importance (e.g., a supervisor or potential employer) will have access to their results. When it is for self-development or research, individuals are less likely to fake their answers to trait EI measures (see Tett et al., 2012 ). We also note that the theoretical bases of trait and mixed measures have also been questioned. Some have argued for example that self-report measures of EI measure nothing fundamentally different from the Big Five (e.g., Davies et al., 1998 ). We will not address this issue here as it has been extensively discussed elsewhere (e.g., Bucich and MacCann, 2019 ) however we emphasize that regardless of the statistical distinctiveness of self-report measures of EI, there is little question regarding their utility and predictive validity ( O'Boyle et al., 2011 ; Miao et al., 2017 ).

One advantage of ability based measures is that they cannot be faked. Test-takers are told to give the answer they believe is correct, and consequently should try to obtain a score as high as possible. A further advantage is that they are often more engaging tests. Rather than simply rating agreement with statements as in trait based measures, test-takers attempt to solve emotion-related problems, solve puzzles, and rate emotions in pictures.

Overall however, there are a number of fundamental problems with ability based measures. First, many personality and intelligence theorists question the very existence of ability EI, and suggest it is nothing more than intelligence. This claim is supported by high correlations between ability EI and IQ, although some have provided evidence to the contrary (e.g., MacCann et al., 2014 ). Additionally, the common measures of ability EI tend to have relatively poor psychometric properties in terms of reliability and validity. Ability EI measures do not tend to strongly predict outcomes that they theoretically should predict (e.g., O'Boyle et al., 2011 ; Miao et al., 2017 ). Maul (2012) also outlines a comprehensive set of problems with the most widely used ability measure, the MSCEIT, related to consensus-based scoring, reliability, and underrepresentation of the EI construct. Also see Petrides (2011) for a comprehensive critique of ability measures.

General Recommendation for Non-experts Choosing Between Ability and Trait EI

While the distinction between trait, ability and mixed EI is important, we acknowledge that many readers will simply be looking for an overall measure of emotional functioning that can predict personal and professional effectiveness. Therefore, when potential users have no overt preference for trait or ability measures but need to decide, we strongly recommend researchers/ practitioners begin with a trait-based measure of EI . Compared to ability based measures, trait based measures tend to have very good psychometric properties, do not have questionable theoretical bases and correlate moderately and meaningfully with a broad set of outcome variables. In general, we believe that trait based measures are more appropriate for most purposes than ability based measures. That being said, several adequate measures of ability EI exist and these have been reviewed in the Literature Review section. If there is a strong preference to use ability measures of EI then several good options exist as outlined later.

Choosing a Specific Measure of Trait EI

Based on our literature review we suggest that a very good, comprehensive measure of trait EI is the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire, or TEIQue ( Petrides and Furnham, 2001 ). If users are not restricted by time or costs (commercial users need to pay, researchers do not) then the TEIQue is a very good option. The TEIQue is a widely used questionnaire that measures 4 factors and 15 facets of trait EI. It has been cited in more than 2,000 academic studies. It is regarded as a “trait” measure of EI because it is based entirely on self-report responses, and facet scores represent typical behavior rather than maximal performance. There is extensive evidence in support of its reliability and validity ( Andrei et al., 2016 ). The four factors of the TEIQue map on to the broad EI facets present in multiple measures of EI as follows: emotionality = perceiving emotions, self-control = regulating emotions in self, sociability = regulating emotions in others, well-being = strategically utilizing emotions.

One disadvantage of the TEIQue however is that it is not freely available for commercial use. The website states that commercial or quasi-commercial use without permission is prohibited. The test can nevertheless be commercially used for a relatively small fee. The relevant webpage can be found here ( http://psychometriclab.com/ ). A second disadvantage is that the test can be fairly easily faked due to its use of a self-report response scale. However, this is generally only an issue when individuals have a reason for faking (e.g., their score will be seen by someone else and might impact their prospects of being selected for a job) (see Tett et al., 2012 ). Consequently, we do not recommend the TEIQue to be used for personnel selection, but it is relevant for other professional purposes such as in EI training and executive coaching.

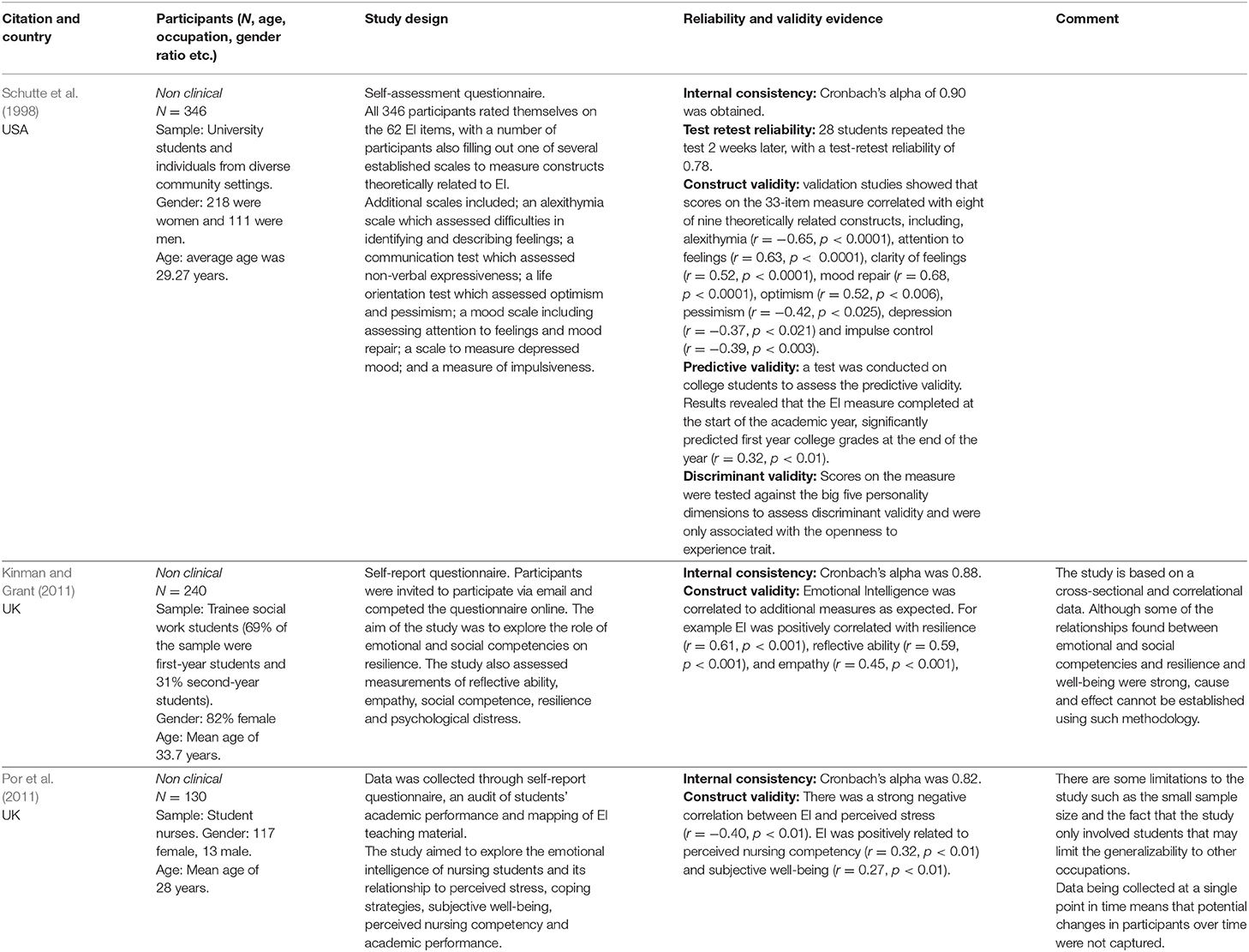

There are very few free measures of trait EI that have been adequately investigated. One exception is the widely used, freely available measure termed the Self-Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SREIT, Schutte et al., 1998 ). The SREIT has been cited more than 3,000 times. The full paper which includes all test items can be accessed here ( https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247166550_Development_and_Validation_of_a_Measure_of_Emotional_Intelligence ). Although it was designed to measure overall EI, subsequent research indicates that it performs better as a multidimensional scale measuring 4 distinct factors including: optimism/mood regulation, appraisal of emotions, social skills and utilization of emotions. These four scales again map closely to the broad facets present in many EI instruments as follows: optimism/mood regulation = regulating emotions in self, appraisal of emotions = perceiving emotions in self, social skills = regulating emotions in others, and utilization of emotions = strategically utilizing emotions. Please note that although one study has comprehensively critiqued the SREIT ( Petrides and Furnham, 2000 ), it actually works well as a multidimensional measure. This was acknowledged by the authors of the critique and has been subsequently confirmed (e.g., by O'Connor and Athota, 2013 ).

Long vs. Short Measures of Trait EI

The TEIQue is available in long form (153 items, 15 facets, 4 factors) and short form (30 items, 4 factors/subscales). A complete description of all factors and facets can be found here ( http://www.psychometriclab.com/adminsdata/files/TEIQue%20interpretations.pdf ). We recommend using the short form when users are interested in measuring only the 4 broad EI factors measured by this questionnaire (self-control, well-being, sociability, emotionality). Additionally, there is much more research on the short form of the questionnaire (e.g., Cooper and Petrides, 2010 ) (see Table 5 ), and the scoring instructions for the short form are freely available for researchers. If the short form is used, it is recommended that all factors/subscales are utilized because they predict outcomes in different ways (e.g., O'Connor and Brown, 2016 ). The SREIT is available only as a short, 33 item measure. All subscales are regarded as equally important and should be included if possible. Again it is noted that this test is freely available and the article publishing the items specifically states “Note: the authors permit free use of the scale for research and clinical purposes.”

When users require a comprehensive measure of trait EI, the long form of the TEIQue is also a good option (see Table 5 ). Although not as widely researched as the short version, the long version nevertheless has strong empirical support for reliability and validity. The long form is likely to be particularly useful for coaching and training purposes, because the use of 15 narrow facets allows for more focused training and intervention than measures with fewer broad facets/factors.

Choosing Between Measures of Ability EI

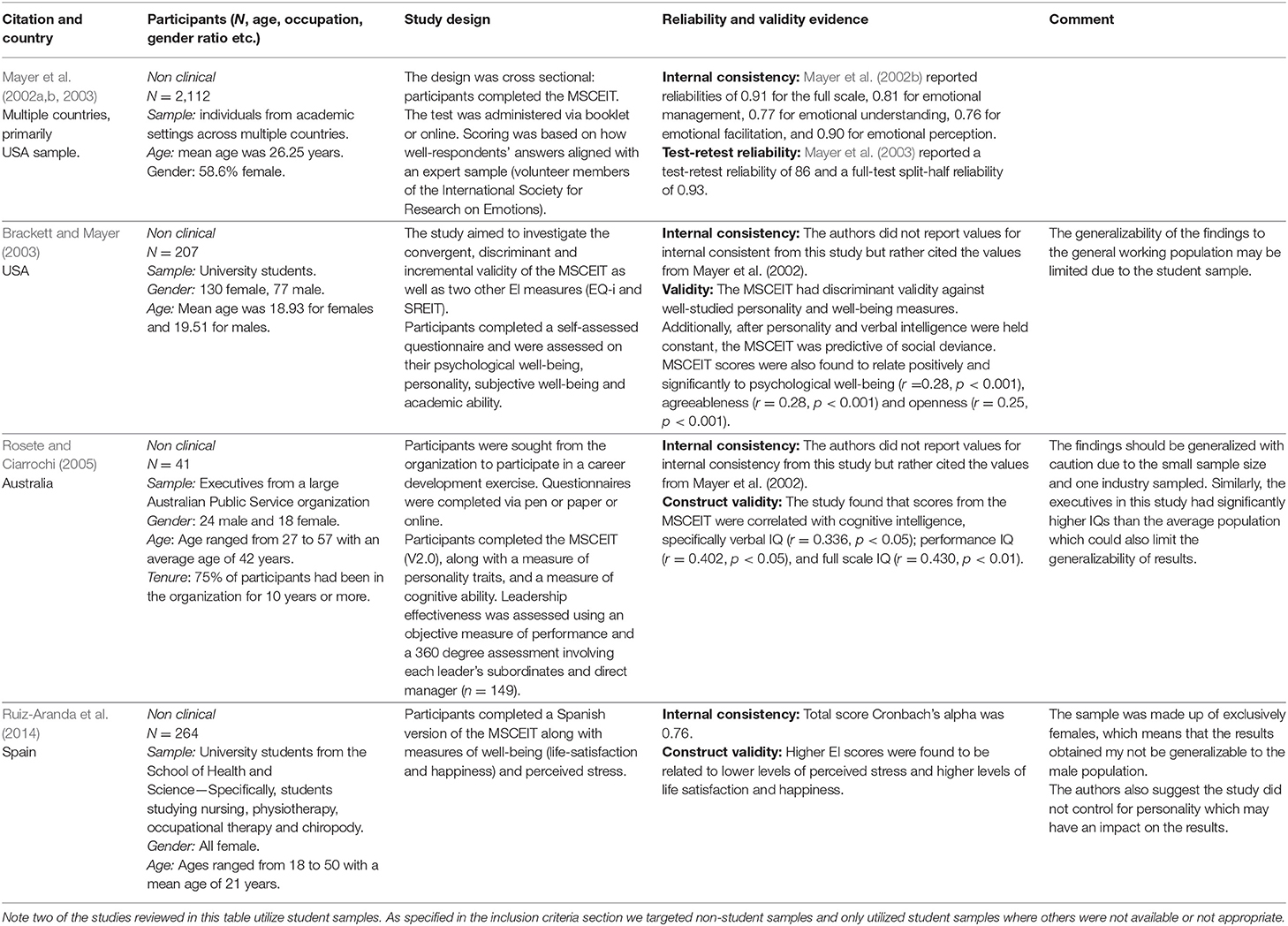

The most researched and supported measure of ability EI is the Mayer, Salovey, Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) (see Tables 2 , 3 ). It has been cited in more than 1,500 academic studies. It uses a 4 branch approach to ability EI and measures ability dimensions of perceiving emotions, facilitating thought, understanding emotions and managing emotions. These scales broadly map onto the broad constructs present in many measures of EI as follows: facilitating thought = strategically utilizing emotions, perceiving emotions = perceiving emotions in self and others, understanding emotions = understanding emotions, and managing emotions = regulating emotions in self and others. However, this is a highly commercialized test and relatively expensive to use. The test is also relatively long (141 items) and time consuming to complete (30–45 min).

A second, potentially more practical option includes two related tests of ability EI designed by MacCann and Roberts (2008) (see Tables 2 , 7 ). These tests are called the Situational Test of Emotion Management (STEM) and the Situational Test of Emotional Understanding (the STEU). These tests are becoming increasingly used in academic articles; the original paper has now been cited more than 250 times. The two aspects of ability EI measured in these tests map neatly onto two of the broad EI constructs present in multiple measures of EI. Specifically, the STEM can be regarded as a measure of emotional regulation in oneself and the STEU can be regarded as a measure of emotional understanding. As indicated in Table 7 , there is strong psychometric support for these tests (although the alpha for STEU is sometimes borderline/low). A further advantage of STEU is that it contains several items regarding workplace behavior, making it highly applicable for use in professional contexts.

If researchers/practitioners decide to use the STEM and STEU, additional measures might be required to measure the remaining broad EI constructs present in other tests. Although these measures could all come from relevant scales of tests reviewed in this article (see Table 1 ), there is a further option. Users should consider the Diagnostic Analysis of Non-verbal Accuracy scale (DANVA) which is a widely used, validated measure of perceiving emotion in others (see Nowicki and Duke, 1994 for an introduction to the DANVA). Alternatively, for those open to using a combination of ability and trait measures, users might wish to use Schutte et al.'s (1998) SREIT to assess remaining facets of EI (see Table 4 ). This is because it is free and captures aspects of EI not measured by STEM/STEU. These include appraisal of emotions (for perceiving emotions) and utilization of emotions (for strategically utilizing emotions), respectively.

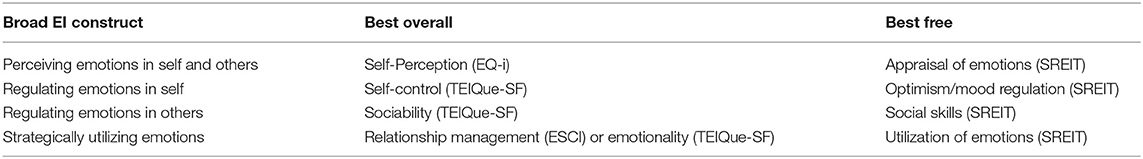

Table 1 . Summary of recommended emotional intelligence assessment measures for each broad EI construct.

Therefore, if there is a strong preference to utilize ability based measures, the STEM, STEU, and DANVA represent some very good options worth considering. The advantage of using these over the MSCEIT is the lower cost of these measures and the reduced test time. Although the STEM, STEU, and DANVA do not seem to be freely available for commercial use, they are nevertheless appropriate for commercial use and likely to be cheaper than alternative options at this point in time.

Deciding Between Using a Single Measure or Multiple Measures

When seeking to measure EI, researchers/practitioners could choose to use (1) a single EI tool that measures overall EI along with common EI facets (i.e., perceiving emotions in self and others, regulating emotions in self and others and strategically utilizing emotions) or (2) some combination of existing scales from EI tool/s to cumulatively measure the four constructs.

The first option represents the most pragmatic and generally optimal solution because all information about the relevant facets and related measures would usually be located in a single document (e.g., test manual, journal article) or website. Additionally, if a paid test is used it would only require a single payment to a single author/institution. Furthermore, single EI tools are generally based on theoretical models of EI that have implications for training and development. For example EI facets in Goleman's (1995 ) model (as measured using the ESCI, Boyatzis and Goleman, 2007 ) are regarded as characteristics that can be trained. Therefore, if a single EI tool is selected, the theory underlying the tool could be used to model the interventions.

However, a disadvantage of the first option is that some EI measures will not contain the specific set of EI constructs researchers/practitioners are interested in assessing. This will often be the case when practitioners are seeking a comprehensive measure of EI but prefer a freely available measure. The second option specified above would solve this problem. However, the trade-off would be increased complexity and the absence of a single underlying theory that relates to the selected measures. Tables 2 – 8 describe facets within each measure as well as reliability and validity evidence for each facet and can be used to assist the selection of multiple measures if users choose to do this.

Table 2 . Summary of major emotional Intelligence assessment measures.

Table 3 . Review of selected studies detailing psychometric properties of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT).

Table 4 . Review of selected studies detailing psychometric properties of the Self-report Emotional Intelligence Test (SREIT).

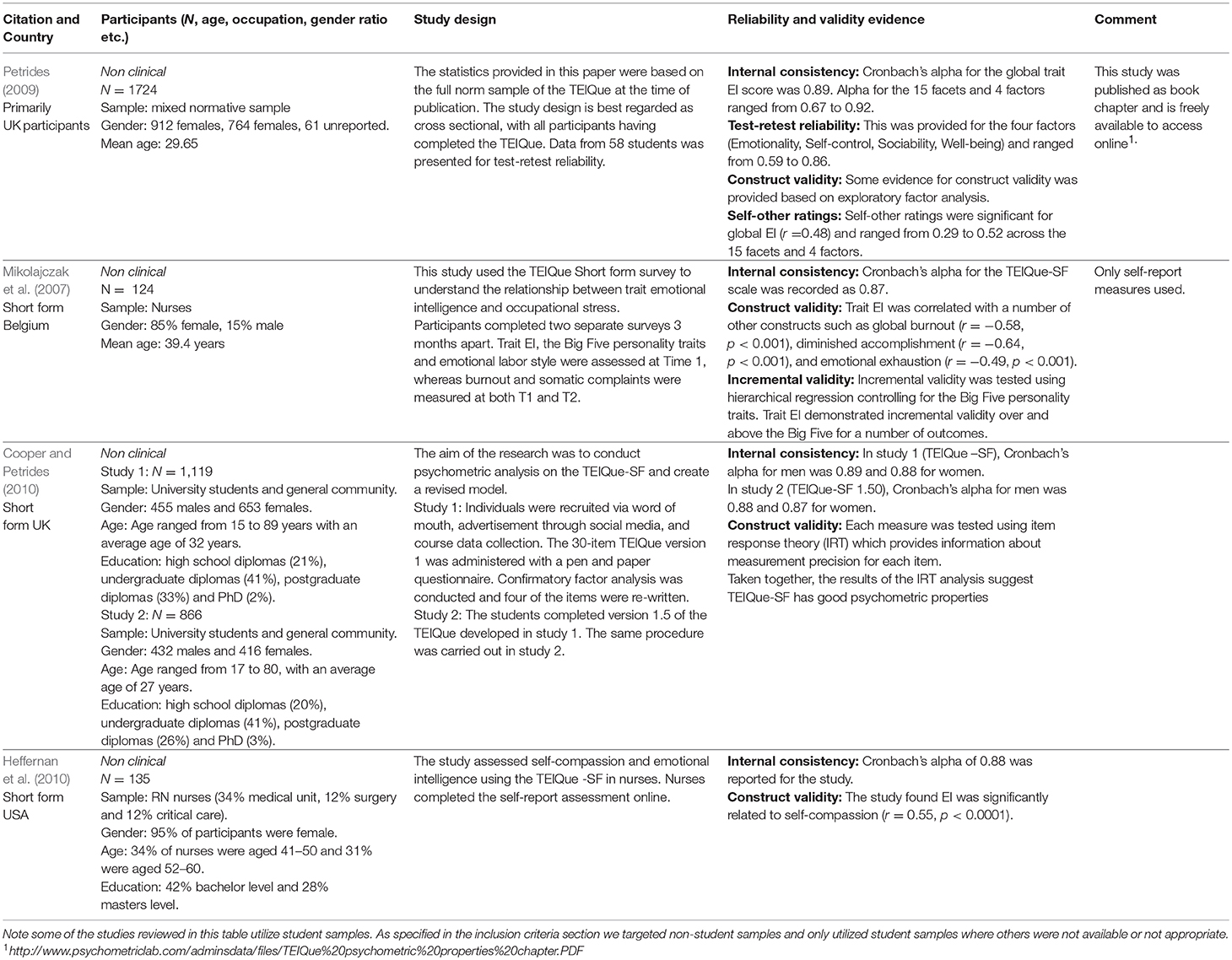

Table 5 . Review of selected studies on psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue).

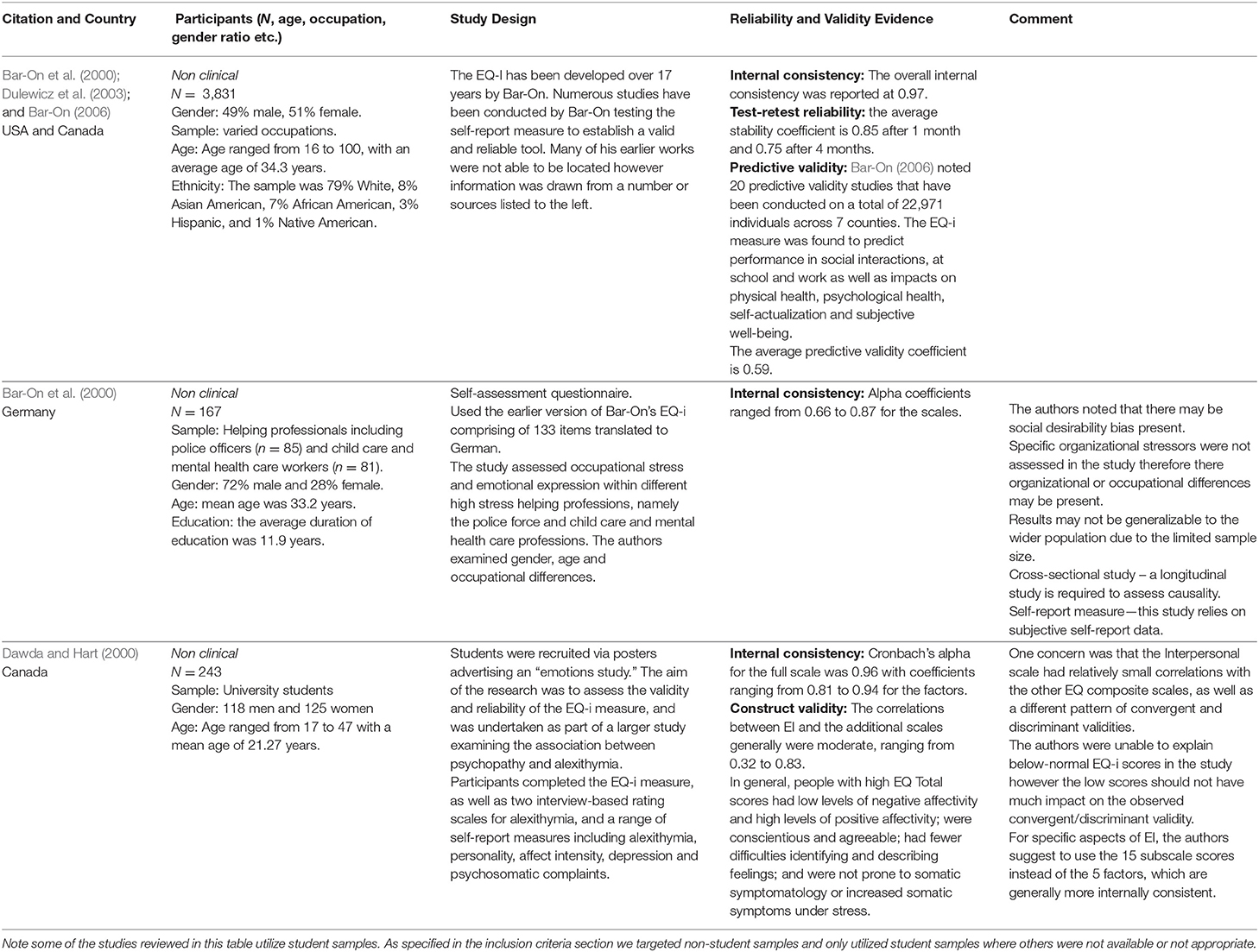

Table 6 . Review of selected studies on psychometric properties of the Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) ( Bar-On, 1997a , b ).

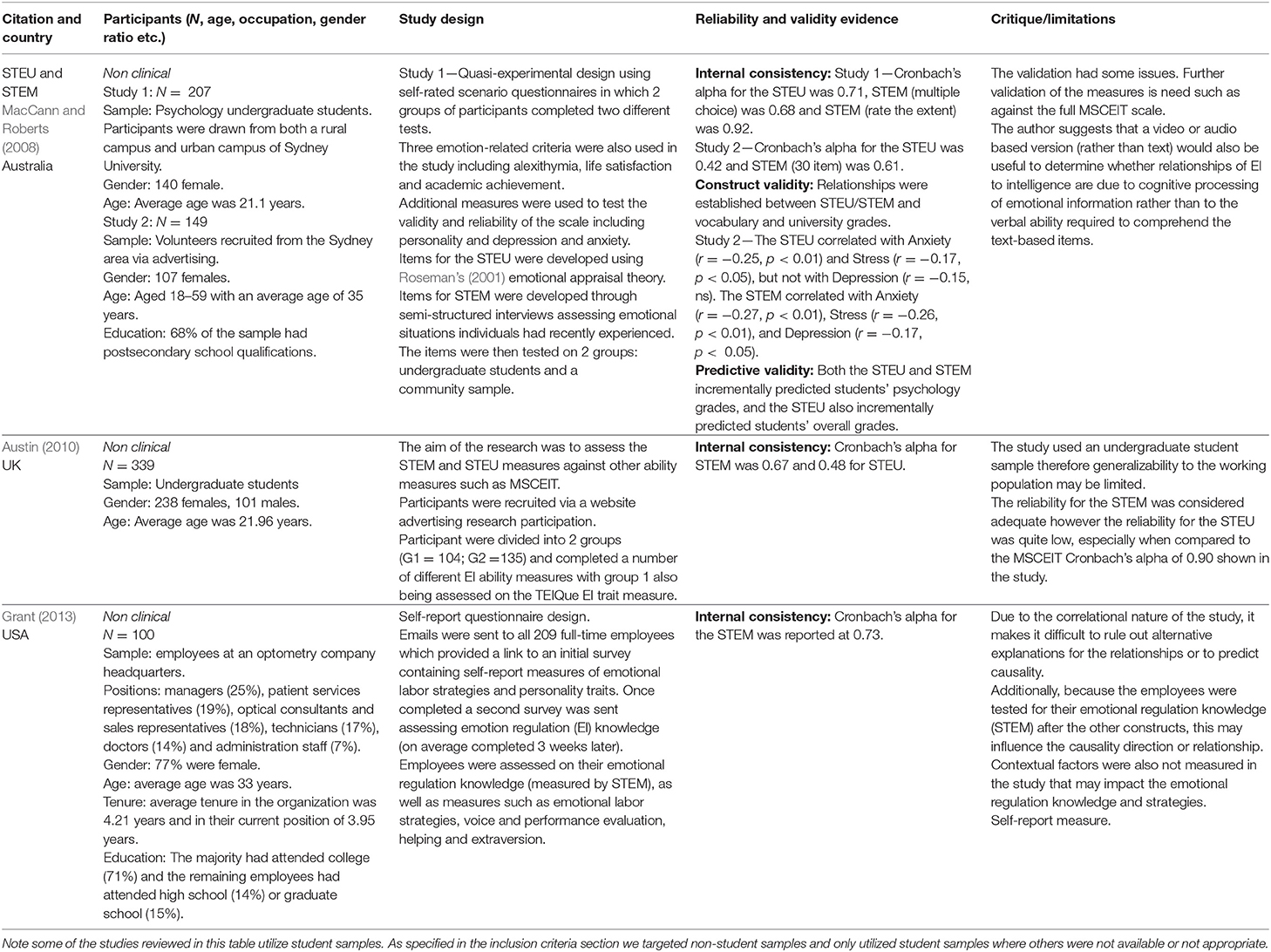

Table 7 . Review of selected studies on psychometric properties of the STEU and STEM.

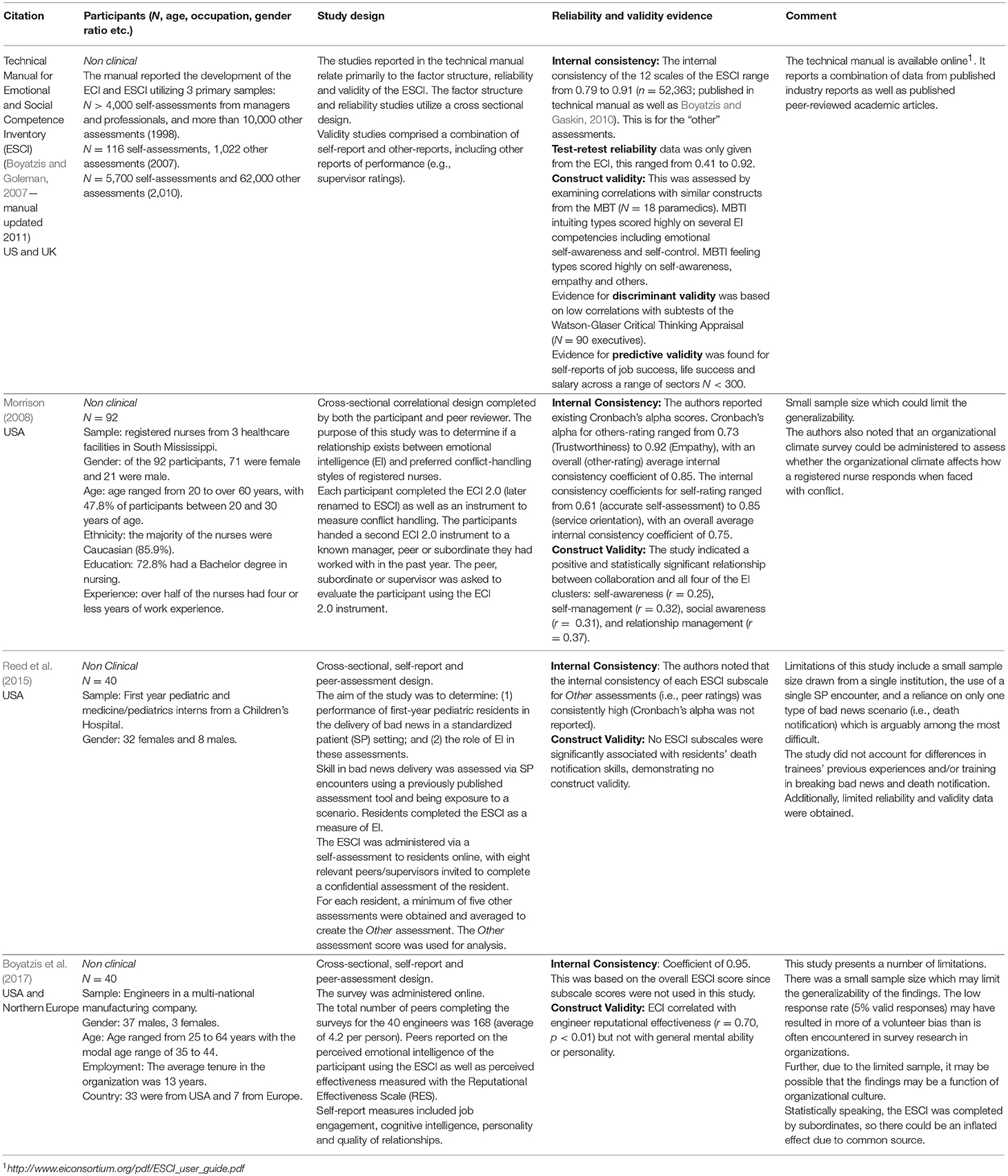

Table 8 . Review of selected studies on psychometric properties of the Emotional and Social competence Inventory (ESCI).

The Best Measure of Each Broad EI Construct (Evaluated Across all Reviewed Tests)

In some cases, researchers/practitioners will not need to measure overall EI, but instead seek to measure a single dimension of EI (e.g., emotion perception, emotion management etc.). In general, we caution the selective use of individual EI scales and recommend that users habitually measure and control for EI facets they are not directly interested in. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that in some cases users will have to select a single measure and consequently, this section specifies a selection of what we consider the “best” measures for each construct. We do this for both free measures and those requiring payment. In order to determine which measure constitutes the “best” measure for each construct, the following criteria were applied:

1. The measure should have been used in multiple research studies published in high quality journals.

2. There should be good evidence for the reliability of the measure in multiple academic studies incorporating the measure.

3. The measure should have obtained adequate validity evidence in multiple academic studies. Most importantly, evidence of construct validity should have been established, including findings demonstrating that the measure correlates meaningfully with measures of related constructs.

4. The measure should be based on a strong and well-supported theory of EI.

5. The measure should be practical (i.e., easy to administer, quickly completed and scored).

Where multiple measures met the above criteria, they were compared on their performance on each criterion (i.e., a measure with a lot of research scored higher on the first criteria than a measure with a medium level of research). Table 1 summarizes these results.

Please note that the Emotional and Social Intelligence Inventory (ESCI) by Boyatzis and Goleman (2007) has subscales that are also closely related to the ones listed in Table 1 (see full technical manual here ( http://www.eiconsortium.org/pdf/ESCI_user_guide.pdf ). The measure was developed primarily to predict and enhance performance at work and items are generally written to reflect workplace scenarios. Subscales from this test were not consistently chosen as the “best” measures because it has not had as extensive published research as the other tests. Most research using this measure has also used peer-ratings rather than self-ratings which makes it difficult to compare with the majority of measures (this is not a weakness though). Nevertheless, it should be considered if cost is not an issue and there is a strong desire to utilize a test specifically developed for the workplace.

Qualifications and Training

Although our purpose in this paper is not to outline the necessary training or qualifications required to administer the set of tests/questionnaires reviewed, we feel it is important to make some comments on this. First, we recommend that all researchers and practitioners considering using one more of these tests have a good understanding of the principles of psychological assessment. Users should understand the concepts of reliability, validity and the role of norms in psychological testing. There are many good introductory texts in this area (e.g., Kaplan and Saccuzzo, 2017 ). Furthermore, we recommend users have a good understanding of the limitations of psychological testing and assessment. When using EI measures to evaluate suitability of job applicants, these measures should form only part of the assessment process and should not be regarded as comprehensive information about applicants. Finally, some of the tests outlined in this review require specific certification and/or qualifications. Certification and/or qualification is required for administrators of the ESCI, MSCEIT, and EQi 2.0).

Literature Review

The final section of this article is a literature review of the 6 popular measures we have covered. We have included our review at the end of this article because we regard it as optional reading. We suggest that this section will be useful primarily for those seeking a more in depth understanding of the key studies underlying the various measures we have presented in earlier sections.

This literature review had two related aims; first to identify prominent EI measures used in the literature, as well as specifically in applied (e.g., health care) contexts. The emotional intelligence measures we included were those that measured both overall EI as well as more specific EI constructs common to multiple measures (e.g., those related to perceiving emotions in self and others, regulating emotions in self and others and strategically utilizing emotions). The second aim was to identify individual studies that have explored the validity and reliability of the specific emotional intelligence measures identified.

Inclusion Criteria

Four main inclusion criteria were applied to select literature: (a) focus on adult samples, (b) use of reputable, peer-reviewed journal articles, (c) use of an EI scale, and (d) where possible, use of a professional sample (e.g., health care professionals) rather than primarily student samples. The literature search therefore focused on empirical, quantitative investigations published in peer-reviewed journals. The articles reviewed therefore were generally methodologically sound and enabled a thorough analysis of some aspect of reliability or validity. We only reviewed articles published after 1990. Additionally, only papers in English were reviewed.

Papers were identified by conducting searches in the following electronic databases: PsycINFO, Medline, PubMED, CINAHL (Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature), EBSCO host and Google Scholar. Individual journals were also scanned such as The Journal of Nursing Measurement and Psychological Assessment.

Search Terms

When searching for emotional intelligence scales and related literature, search terms included: trait emotional intelligence, ability emotional intelligence, emotional intelligence scales, mixed emotional intelligence and emotional intelligence measures. Some common EI facet titles (e.g., self-awareness, self-regulation/self-management, social awareness, and relationship management) were also entered as search terms however this revealed far less relevant literature than searches based on EI terms. To access studies using professionals we also used terms such as workplace, healthcare, and nursing, along with emotional intelligence.

When searching for literature on the identified scales, the name of the respective scale was included in the search term (such as TEIQue scale) and the authors' names, along with terms such as workplace, organization, health care, nurses, health care professionals, to identify specific studies with a professional employee sample that utilized the specific scale. The terms validity and reliability were also used. Additionally, a similar search was conducted on articles that had cited the original papers. This search was done conducted utilizing Google Scholar. Table 2 summarizes the result of the first part of the literature review. It provides an overview of major Emotional Intelligence assessment measures, in terms of when they were developed, who developed them, what form of EI they measure, theoretical basis, test length and details regarding cost.

Tables 3 – 8 summarize research on the validity and reliability of the 6 tests included in Table 2 . In these tables we summarize the methodology used in major studies assessing reliability and validity as well as the results from these studies.

Collectively, these tables indicate that all 6 of the measures we reviewed have received some support for their reliability and validity. Measures with extensive research include the MSCEIT, SREIT, and TEIQue, and EQ-I and those with less total research are the STEU/STEM and ESCI. Existing research does not indicate that these latter measures are any less valid or reliable that the others; on the contrary they are promising measures but require further tests of reliability and validity. As noted previously, this table confirms that the tests with the strongest current evidence for construct and predictive validity are the self-report/trait EI measures (TEIQue, EQ-I, and SREIT). We note that although there is evidence for construct validity of the SREIT based on associations with theoretically related constructs (e.g., alexithymia, optimism; see Table 4 ), some have suggested the measure is problematic due to its use of self-report questions that primarily measure ability based constructs (see Petrides and Furnham, 2000 ).

In this article we have reviewed six widely used measures of EI and made recommendations regarding their appropriate use. This article was written primarily for researchers and practitioners who are not currently experts on EI and therefore we also clarified the difference between ability EI, trait EI and mixed EI. Overall, we recommend that users should use single, complete tests where possible and choose measures of EI most suitable for their purpose (i.e., choose ability EI when maximal performance is important and trait EI when typical performance is important). We also point out that, across the majority of emotion-related outcomes, trait EI tends to be a stronger predictor and consequently we suggest that new users of EI consider using a trait-based measure before assessing alternatives. The exception is in employment contexts where tests utilizing 360 degree assessment (primarily mixed measures) can also be very useful.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The QUT library funded the article processing charges for this paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Andrei, F., Siegling, A. B., Aloe, A. M., Baldaro, B., and Petrides, K. V. (2016). The incremental validity of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Personal. Assess. 98, 261–276. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2015.1084630

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ashkanasy, N. M., and Daus, C. S. (2005). Rumors of the death of emotional intelligence in organizational behavior are vastly exaggerated. J. Organiz. Behav. 26, 441–452. doi: 10.1002/job.320

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Austin, E. J. (2010). Measurement of ability emotional intelligence: Results for two new tests. Br. J. Psychol. 101, 563–578. doi: 10.1348/000712609X474370

Austin, E. J., Saklofske, D. H., and Mastoras, S. M. (2010). Emotional intelligence, coping and exam-related stress in Canadian undergraduate students. Austral. J. Psychol. 62, 42–50. doi: 10.1080/00049530903312899

Bar-On, R. (1996). The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): A Test of Emotional Intelligence . Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems.

Google Scholar

Bar-On, R. (1997a). Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory: User's Manual. Toronto, ON: Multihealth Systems.

Bar-On, R. (1997b). The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): Technical manual . Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.

Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema 18, 13–25.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Bar-On, R., Brown, J. M., Kirkcaldy, B. D., and Thomé, E. P. (2000). Emotional expression and implications for occupational stress; an application of the emotional quotient inventory (EQ-i). Personal. Indiv. Differe. 28, 1107–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00160-9

Boyatzis, R., Rochford, K., and Cavanagh, K. V. (2017). Emotional intelligence competencies in engineer's effectiveness and engagement. Career Dev. Int. 22, 70–86. doi: 10.1108/CDI-08-2016-0136

Boyatzis, R. E. (2018). The behavioral level of emotional intelligence and its measurement. Front. Psychol. 9:01438. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01438

Boyatzis, R. E., and Gaskin, J. (2010). A Technical Note on the ESCI and ESCI-U: Factor Structure, Reliability, Convergent and Discriminant Validity Using EFA and CFA . Boston, MA: The Hay Group.

Boyatzis, R. E., and Goleman, D. (2007). Emotional and Social Competency Inventory. Boston, MA: The Hay Group.

Boyatzis, R. E., Goleman, D., and Rhee, K. (2000). “Clustering competence in emotional intelligence: insights from the emotional competence inventory (ECI),”in Handbook of Emotional Intelligence, eds R. Bar-On and J. D. A. Parker (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 343–362

Brackett, M. A., and Mayer, J. D. (2003). Convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence. Personal. Social Psychol. Bull. 29, 1147–1158. doi: 10.1177/0146167203254596

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., and Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: a comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. J. Personal. Social Psychol. 91:780. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780

Bucich, M., and MacCann, C. (2019). Emotional intelligence research in Australia: Past contributions and future directions. Austral. J. Psychol. 71, 59–67. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12231

Conte, J. M. (2005). A review and critique of emotional intelligence measures. J. Organiz. Behav. 26, 433–440. doi: 10.1002/job.319

Cooper, A., and Petrides, K. (2010). A psychometric analysis of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire–short form (TEIQue–SF) using item response theory. J. Personal. Assess. 92, 449–457. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.497426

Davies, M., Stankov, L., and Roberts, R. D. (1998). Emotional intelligence: in search of an elusive construct. J. Personal. Social Psychol. 75:989. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.989

Davis, S. K., and Humphrey, N. (2014). Ability versus trait emotional intelligence. J. Indiv. Differ. 35, 54–52. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000127

Dawda, D., and Hart, S. D. (2000). Assessing emotional intelligence: reliability and validity of the bar-on emotional quotient inventory (EQ-i) in university students. Personal. Indiv. Diff. 28, 797–812. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00139-7

Dulewicz, V., Higgs, M., and Slaski, M. (2003). Measuring emotional intelligence: content, construct and criterion-related validity. J. Manag. Psychol. 18, 405–420. doi: 10.1108/02683940310484017

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence . New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Grant, A. M. (2013). Rocking the boat but keeping it steady: The role of emotion regulation in employee voice. Acad. Manag. J. 56, 1703–1723. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0035

Gutiérrez-Cobo, M. J., Cabello, R., and Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2016). The relationship between emotional intelligence and cool and hot cognitive processes: a systematic review. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10:101. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00101

Heffernan, M., Quinn Griffin, M. T., Sister Rita McNulty, S. R., and Fitzpatrick, J. J. (2010). Self-compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 16, 366–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01853.x

Kaplan, R. M., and Saccuzzo, D. P. (2017). Psychological Testing: Principles, Applications, and Issues . Mason, OH: Nelson Education.

Kinman, G., and Grant, L. (2011). Exploring stress resilience in trainee social workers: the role of emotional and social competencies. Br. J. Social Work 41, 261–275. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcq088

Kun, B., and Demetrovics, Z. (2010). Emotional intelligence and addictions: a systematic review. Subst. Misuse 45, 1131–1160. doi: 10.3109/10826080903567855

MacCann, C. (2006). Appendix 2.1 Instructions and Items in STEU (Situational Test of Emotional Understanding). Retrieved from: https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/934/3/03Appendices.pdf

MacCann, C., Joseph, D. L., Newman, D. A., and Roberts, R. D. (2014). Emotional intelligence is a second-stratum factor of intelligence: evidence from hierarchical and bifactor models. Emotion 14, 358–374. doi: 10.1037/a0034755

MacCann, C., and Roberts, R. D. (2008). New paradigms for assessing emotional intelligence: theory and data. Emotion 8, 540–551. doi: 10.1037/a0012746

Maul, A. (2012). The validity of the mayer–salovey–caruso emotional intelligence test (MSCEIT) as a measure of emotional intelligence. Emot. Rev. 4, 394–402. doi: 10.1177/1754073912445811

Mavroveli, S., and Sánchez-Ruiz, M. J. (2011). Trait emotional intelligence influences on academic achievement and school behaviour. Br. J. Edu. Psychol. 81, 112–134. doi: 10.1348/2044-8279.002009

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., and Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence 27, 267–298. doi: 10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00016-1

Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., and Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol . 59, 507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D., and Sternberg, R. J. (2000). Models of Emotional Intelligence , ed R. J. Sternberg (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 396–420.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., and Caruso, D. R. (2002a). Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) Item Booklet . Toronto, ON: MHS Publishers.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., and Caruso, D. R. (2002b). Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) User's Manual . Toronto, ON: MHS Publishers.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D. R., and Sitarenios, G. (2001). Emotional intelligence as a standard intelligence. Emotion 1, 232–242. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.232

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Caruso, D. R., and Sitarenios, G. (2003). Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2. 0. Emotion 3 , 97–105. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97

Miao, C., Humphrey, R. H., and Qian, S. (2017). A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and work attitudes. J. Occupat. Organiz. Psychol. 90, 177–202. doi: 10.1111/joop.12167

Mikolajczak, M., Menil, C., and Luminet, O. (2007). Explaining the protective effect of trait emotional intelligence regarding occupational stress: exploration of emotional labour processes. J. Res. Person. 41, 1107–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.01.003

Morrison, J. (2008). The relationship between emotional intelligence competencies and preferred conflict-handling styles. J. Nurs. Manage. 16, 974–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00876.x

Nowicki, S., and Duke, M. P. (1994). Individual differences in the nonverbal communication of affect: the diagnostic analysis of nonverbal accuracy scale. J. Nonverb. Behav. 18, 9–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02169077

O'Boyle, E. H. Jr., Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., Hawver, T. H., and Story, P. A. (2011). The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: a meta-analysis. J. Organiz. Beha. 32, 788–818. doi: 10.1002/job.714

O'Connor, P., Nguyen, J., and Anglim, J. (2017). Effectively coping with task stress: a study of the validity of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire–short form (TEIQue–SF). J. Personal. Assess. 99, 304–314. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2016.1226175

O'Connor, P. J., and Athota, V. S. (2013). The intervening role of Agreeableness in the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and machiavellianism: reassessing the potential dark side of EI. Personal. Indiv. Differe. 55, 750–754. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.06.006

O'Connor, P. J., and Brown, C. M. (2016). Sex-linked personality traits and stress: emotional skills protect feminine women from stress but not feminine men. Personal. Indiv. Differe. 99, 28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.075

Palmer, B. R., Stough, C., Harmer, R., and Gignac, G. (2009). “The genos emotional intelligence inventory: a measure designed specifically for workplace applications.” in Assessing Emotional Intelligence (Boston, MA: Springer), 103–117.

Pérez, J. C., Petrides, K. V., and Furnham, A. (2005). Measuring Trait Emotional Intelligence. Emotional intelligence: An International Handbook , ed R. Schulze and R. D. Roberts (Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber), 181–201.

Petrides, K. V. (2009). “Psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire,” in Advances in the Assessment of Emotional Intelligence , eds C. Stough, D. H. Saklofske and J. D. Parker (New York, NY: Springer), 85–101.

Petrides, K. V. (2011). “Ability and trait emotional intelligence,” in The Blackwell-Wiley Handbook of Individual Differences , eds T. Chamorro-Premuzic, A. Furnham, and S. von Stumm (New York, NY: Wiley).

Petrides, K. V., and Furnham, A. (2000). On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence. Personal. Indivi. Differ. 29, 313–320. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00195-6

Petrides, K. V., and Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. Eur. J. Person. 15, 425–448. doi: 10.1002/per.416

Petrides, K. V., Mikolajczak, M., Mavroveli, S., Sanchez-Ruiz, M. J., Furnham, A., and Pérez-González, J. C. (2016). Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev. 8, 335–341. doi: 10.1177/1754073916650493

Por, J., Barriball, L., Fitzpatrick, J., and Roberts, J. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Its relationship to stress, coping, well-being and professional performance in nursing students. Nurse Edu. Today 31, 855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.12.023

Reed, S., Kassis, K., Nagel, R., Verbeck, N., Mahan, J. D., and Shell, R. (2015). Does emotional intelligence predict breaking bad news skills in pediatric interns? A pilot study. Med. Edu. Online 20:e24245. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.24245

Roberts, R. D., Zeidner, M., and Matthews, G. (2001). Does emotional intelligence meet traditional standards for an intelligence? Some new data and conclusions. Emotion 1:196. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.196

Roseman, I. J. (2001). A Model of Appraisal in the Emotion System. Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research , ed K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr and T. Johnstone (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 68–91.

Rosete, D., and Ciarrochi, J. (2005). Emotional intelligence and its relationship to workplace performance outcomes of leadership effectiveness. Leadership Organiz. Dev. J. 26, 388–399. doi: 10.1108/01437730510607871

Ruiz-Aranda, D., Extremera, N., and Pineda-Galán, C. (2014). Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction and subjective happiness in female student health professionals: the mediating effect of perceived stress. J. Psychia. Mental Health Nurs. 21, 106–113. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12052

Salovey, P., and Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imag. Cogn. Persona. 9, 185–211. doi: 10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Schlegel, K., and Mortillaro, M. (2019). The Geneva Emotional Competence Test (GECo): an ability measure of workplace emotional intelligence. J. Appl. Psychol. 104, 559–580. doi: 10.1037/apl0000365

Schultz, D., Izard, C. E., and Bear, G. (2004). Children's emotion processing: Relations to emotionality and aggression. Dev. Psychopathol. 16, 371–387. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404044566

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Cooper, J. T., Golden, C. J., et al. (1998). Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personal. Indivi. Diff. 25, 167–177. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00001-4

Sheldon, O. J., Dunning, D., and Ames, D. R. (2014). Emotionally unskilled, unaware, and uninterested in learning more: reactions to feedback about deficits in emotional intelligence. J. Appl. Psychol. 99, 125–137. doi: 10.1037/a0034138

Siegling, A. B., Saklofske, D. H., and Petrides, K. V. (2015). Measures of ability and trait emotional intelligence. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Constructs , eds G. J. Boyle, G. Matthews, and D. H. Saklofske (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 381–414.

Tett, R. P., Freund, K. A., Christiansen, N. D., Fox, K. E., and Coaster, J. (2012). Faking on self-report emotional intelligence and personality tests: Effects of faking opportunity, cognitive ability, and job type. Personal. Indivi. Diffe. 52, 195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.017

Van Rooy, D. L., Viswesvaran, C., and Pluta, P. (2005). An evaluation of construct validity: What is this thing called emotional intelligence? Hum. Perform. 18, 445–462. doi: 10.1207/s15327043hup1804_9

Wong, C. S., Law, K. S., and Wong, P. M. (2004). Development and validation of a forced choice emotional intelligence for Chinese respondents in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific J. Manage. 21, 535–559. doi: 10.1023/B:APJM.0000048717.31261.d0

Wong, C. S., Wong, P. M., and Law, K. S. (2007). Evidence of the practical utility of Wong's emotional intelligence scale in Hong Kong and mainland China. Asia Pac. J. Manage. 24, 43–60. doi: 10.1007/s10490-006-9024-1

Keywords: emotional intelligence, measures, questionnaires, trait, ability, mixed, recommendations

Citation: O'Connor PJ, Hill A, Kaya M and Martin B (2019) The Measurement of Emotional Intelligence: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommendations for Researchers and Practitioners. Front. Psychol. 10:1116. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01116

Received: 05 October 2018; Accepted: 29 April 2019; Published: 28 May 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 O'Connor, Hill, Kaya and Martin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peter J. O'Connor, peter.oconnor@qut.edu.au

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Measurement of Emotional Intelligence: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommendations for Researchers and Practitioners

Peter j. o'connor.

1 School of Management, QUT Business School, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Andrew Hill

2 Clinical Skills Development Service, Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Queensland Health, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

3 School of Psychology, Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD, Australia

4 School of Advertising, Marketing and Public Relations, QUT Business School, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Brett Martin

Emotional Intelligence (EI) emerged in the 1990s as an ability based construct analogous to general Intelligence. However, over the past 3 decades two further, conceptually distinct forms of EI have emerged (often termed “trait EI” and “mixed model EI”) along with a large number of psychometric tools designed to measure these forms. Currently more than 30 different widely-used measures of EI have been developed. Although there is some clarity within the EI field regarding the types of EI and their respective measures, those external to the field are faced with a seemingly complex EI literature, overlapping terminology, and multiple published measures. In this paper we seek to provide guidance to researchers and practitioners seeking to utilize EI in their work. We first provide an overview of the different conceptualizations of EI. We then provide a set of recommendations for practitioners and researchers regarding the most appropriate measures of EI for a range of different purposes. We provide guidance both on how to select and use different measures of EI. We conclude with a comprehensive review of the major measures of EI in terms of factor structure, reliability, and validity.

Overview and Purpose

The purpose of this article is to review major, widely-used measures of Emotional Intelligence (EI) and make recommendations regarding their appropriate use. This article is written primarily for academics and practitioners who are not currently experts on EI but who are considering utilizing EI in their research and/or practice. For ease of reading therefore, we begin this article with an introduction to the different types of EI, followed by a brief summary of different measures of EI and their respective facets. We then provide a detailed set of recommendations for researchers and practitioners. Recommendations focus primarily on choosing between EI constructs (ability EI, trait EI, mixed models) as well as choosing between specific tests. We take into account such factors as test length, number of facets measured and whether tests are freely available. Consequently we also provide recommendations both for users willing to purchase tests and those preferring to utilize freely available measures.

In our detailed literature review, we focus on a set of widely used measures and summarize evidence for their validity, reliability, and conceptual basis. Our review includes studies that focus purely on psychometric properties of EI measures as well as studies conducted within applied settings, particularly health care settings. We include comprehensive tables summarizing key empirical studies on each measure, in terms of their research design and main findings. Our review includes measures that are academic and/or commercial as well as those that are freely available or require payment. To assist users with accessing measures, we include web links to complete EI questionaries for freely available measures and to websites and/or example items for copyrighted measures. For readers interested in reviews relating primarily to EI constructs, theory and outcomes rather than specifically measures of EI, we recommend a number of recent high quality publications (e.g., Kun and Demetrovics, 2010 ; Gutiérrez-Cobo et al., 2016 ). Additionally, for readers interested in a review of measures without the extensive recommendations we provide here, we recommend the chapter by Siegling et al. ( 2015 ).

Early Research on Emotional Intelligence

EI emerged as a major psychological construct in the early 1990s, where it was conceptualized as a set of abilities largely analogous to general intelligence. Early influential work on EI was conducted by Salovey and Mayer ( 1990 ), who defined EI as the “the ability to monitor one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions” (p. 189). They argued that individuals high in EI had certain emotional abilities and skills related to appraising and regulating emotions in the self and others. Accordingly, it was argued that individuals high in EI could accurately perceive certain emotions in themselves and others (e.g., anger, sadness) and also regulate emotions in themselves and others in order to achieve a range of adaptive outcomes or emotional states (e.g., motivation, creative thinking).

However, despite having a clear definition and conceptual basis, early research on EI was characterized by the development of multiple measures (e.g., Bar-On, 1997a , b ; Schutte et al., 1998 ; Mayer et al., 1999 ) with varying degrees of similarity (see Van Rooy et al., 2005 ). One cause of this proliferation was the commercial opportunities such tests offered to developers and the difficulties faced by researchers seeking to obtain copyrighted measures (see section Mixed EI for a summary of commercial measures). A further cause of this proliferation was the difficulty researchers faced in developing measures with good psychometric properties. A comprehensive discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this article (see Petrides, 2011 for more details) however one clear challenge faced by early EI test developers was constructing emotion-focused questions that could be scored with objective criteria. In comparison to measures of cognitive ability that have objectively right/wrong answers (e.g., mathematical problems), items designed to measure emotional abilities often rely on expert judgment to define correct answers which is problematic for multiple reasons (Roberts et al., 2001 ; Maul, 2012 ).

A further characteristic of many early measures was their failure to discriminate between measures of typical and maximal performance. In particular, some test developers moved away from pure ability based questions and utilized self-report questions (i.e., questions asking participants to rate behavioral tendencies and/or abilities rather than objectively assessing their abilities; e.g., Schutte et al., 1998 ). Other measures utilized broader definitions of EI that included social effectiveness in addition to typical EI facets (see Ashkanasy and Daus, 2005 ) (e.g., Boyatzis et al., 2000 ; Boyatzis and Goleman, 2007 ). Over time it became clear that these different measures were tapping into related, yet distinct underlying constructs. Currently, there are two popular methods of classifying EI measures. First is the distinction between trait and ability EI proposed initially by Petrides and Furnham ( 2000 ) and further clarified by Pérez et al. ( 2005 ). Second is in terms of the three EI “streams” as proposed by Ashkanasy and Daus ( 2005 ). Fortunately there is overlap between these two methods of classification as we discuss below.

Methods of Classifying EI

The distinction between ability EI and trait EI first proposed by Petrides and Furnham ( 2000 ) was based purely on whether the measure was a test of maximal performance (ability EI) or a self-report questionnaire (trait EI) (Petrides and Furnham, 2000 ; Pérez et al., 2005 ). According to this method of classification, Ability EI tests measure constructs related to an individual's theoretical understanding of emotions and emotional functioning, whereas trait EI questionnaires measure typical behaviors in emotion-relevant situations (e.g., when an individual is confronted with stress or an upset friend) as well as self-rated abilities. Importantly, the key aspect of this method of classification is that EI type is best defined by method of measurement: all EI measures that are based on self-report items are termed “trait EI” whereas all measures that are based on maximal performance items are termed “ability EI”.

The second popular method of classifying EI measures refers the three EI “streams” (Ashkanasy and Daus, 2005 ). According to this method of classification, stream 1 includes ability measures based on Mayer and Salovey's model; stream 2 includes self-report measures based on Mayer and Salovey's model and stream 3 includes “expanded models of emotional intelligence that encompass components not included in Salovey and Mayer's definition” (p. 443). Ashkanasy and Daus ( 2005 ) noted that stream 3 had also been referred to as “mixed” models in that they comprise a mixture of personality and behavioral items. The term “mixed EI” is now frequently used in the literature to refer to EI measures that measure a combination of traits, social skills and competencies and overlaps with other personality measures (O'Boyle et al., 2011 ).